Here we go again. It is December, and cases, hospitalizations and wastewater concentrations are all going up. How worried should we be?

We should worry that cases will for a time double or triple from where they are. Combined with flu and RSV, this will mean that while our health care systems will hold, they will be under substantial strain that impacts quality of care. Things are going to low-key suck for a bit, and the number of worthwhile additional precautions to take, overall, will not be zero.

We should not worry that this will be anything like last winter. That is not going to happen, not in terms of cases and not in terms of hospitalizations and deaths. That is not in the cards at all.

Executive Summary

Big jump in cases and hospitalizations likely means winter surge.

Chinese protests suppressed, some modest loosening did result.

Long Covid study finds control group that had other respiratory illnesses did worse than the Covid group.

Let's run the numbers.

The Numbers

Predictions

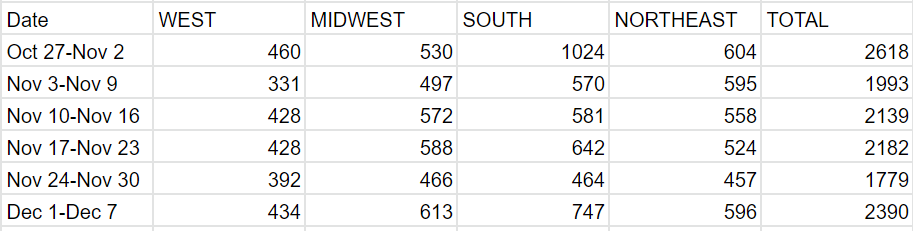

Predictions from Last Week: 290k cases (+5%) and 2,050 deaths (+15%).

Results: 354k cases (+28%) and 2,390 deaths (+34%).

Predictions for Next Week: 371k cases (+5%) and 2,240 deaths (-6%).

The case number reflects a substantially larger expected real increase with the fact that this week’s number likely is about 10% higher than it should be due to holiday reporting issues around Thanksgiving.

The death number is a clear post-holiday spike so I’m expecting a return back down, as the case spike hasn’t had enough time to add to the count much.

Deaths

This is the classic post-holiday story, with deaths being backfilled. That wasn’t certain because the of the case count being unexpectedly high, but it seems clear now. Things should return to normal until Christmas.

Cases

The winter wave is upon us, to the extent we will have one. Cases are up 28% week over week. Hospitalizations are up 19% week over week, likely a better reflection of actual cases given the holiday. How bad is it going to get?

Mathew David is cautiously optimistic we can avoid a large winter wave.

I agree with this. We likely have something like five weeks left before this peaks, with future weeks unlikely to see larger increases than we are seeing now. That puts the realistic bad scenario peak at something like 250% of current levels, similar to the peak in July 2022. What kind of precautions are justified at that level?

Trevor Bedford thread points out that the vast majority of cases are now likely not making it into the statistics, and asks the question of whether this is good news or bad news given what else we know. All the missing cases mean more Covid. They also mean a lower IFR, which he estimates at between 0.04% and 0.07% (which means that if you are not elderly or otherwise at risk, it is that much lower still). If one thinks that every bout with Covid is a terrifying brush with permanent doom, then this is bad news. Otherwise, it seems on net like good news.

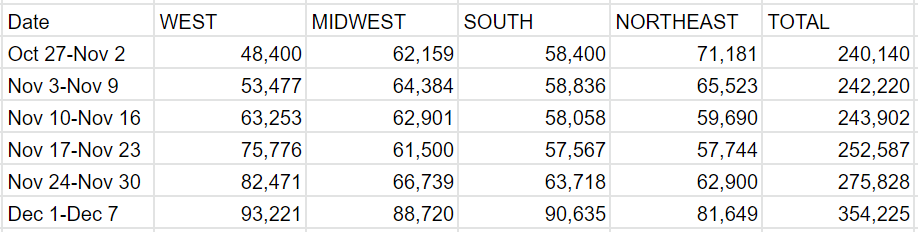

Here is the California wastewater surveillance network dashboard, which shows recent big increases. The easier-to-use site from Boston (which is the source of the graphs below) also shows a clear increase. Neither shows things getting as bad as the summer peak, let alone showing any sign of what we should remember was a truly gigantic peak last winter that makes the rest of the graph all but impossible to read.

Booster Boosting

By all accounts and statistics there’s a lot of flu out there right now, with hospitalizations from it on par with Covid. If you haven’t gotten your flu shot yet, seems like a thing well worth doing. It is said to be a good match to this year’s strains.

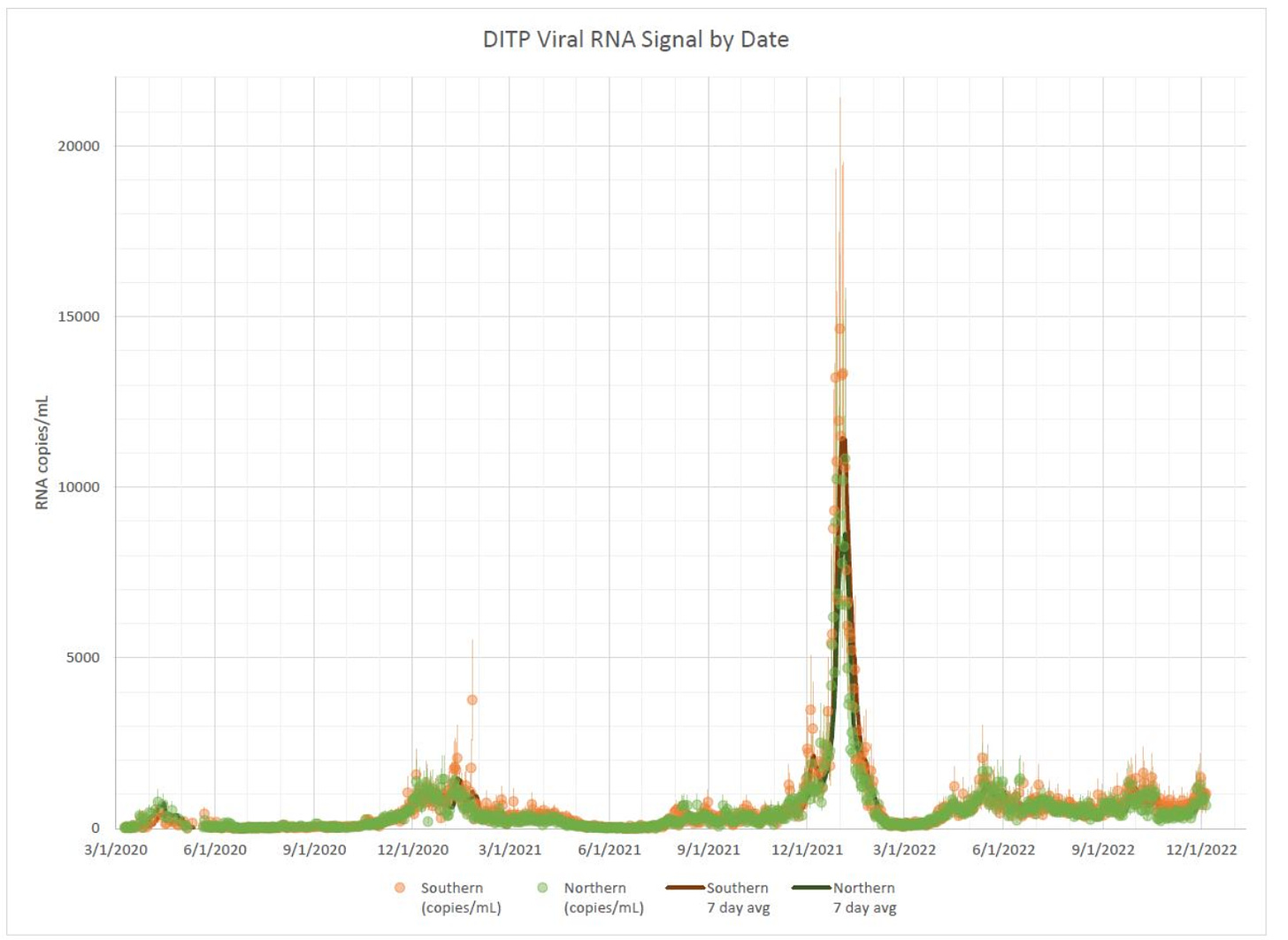

Once again, the usual suspects talk of global Covid waves and respond with ‘therefore you need a booster and to mask up.’

(Ronald was Quote Tweeting the Topol link above.)

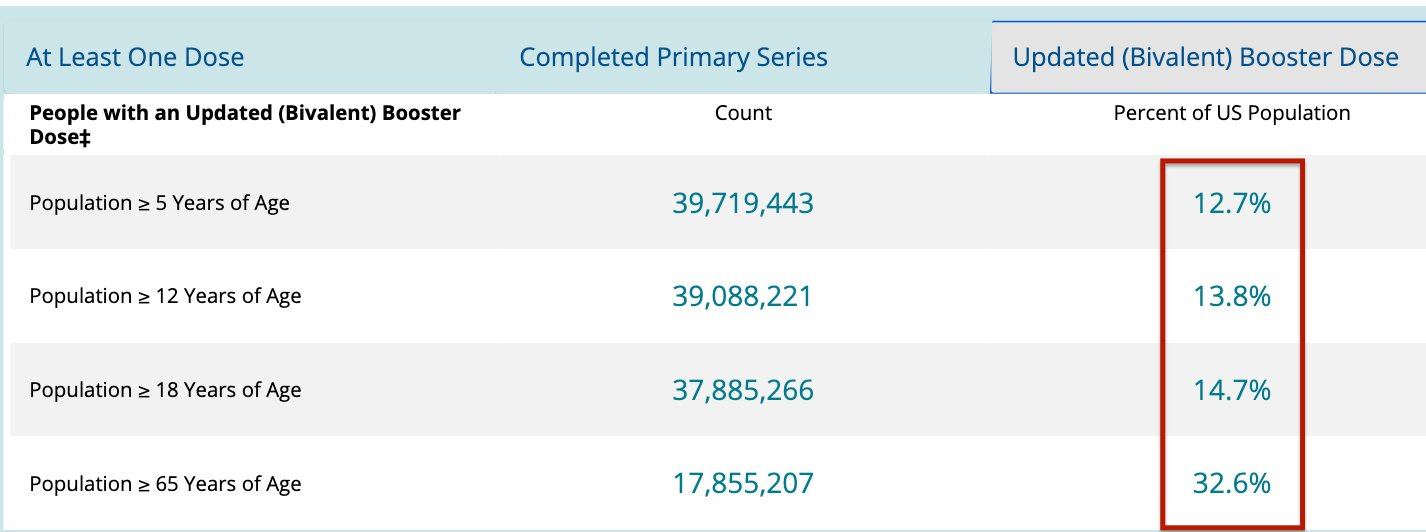

Current progress is not extensive on this. There is relatively a lot more uptake in the over 65 population, which makes sense.

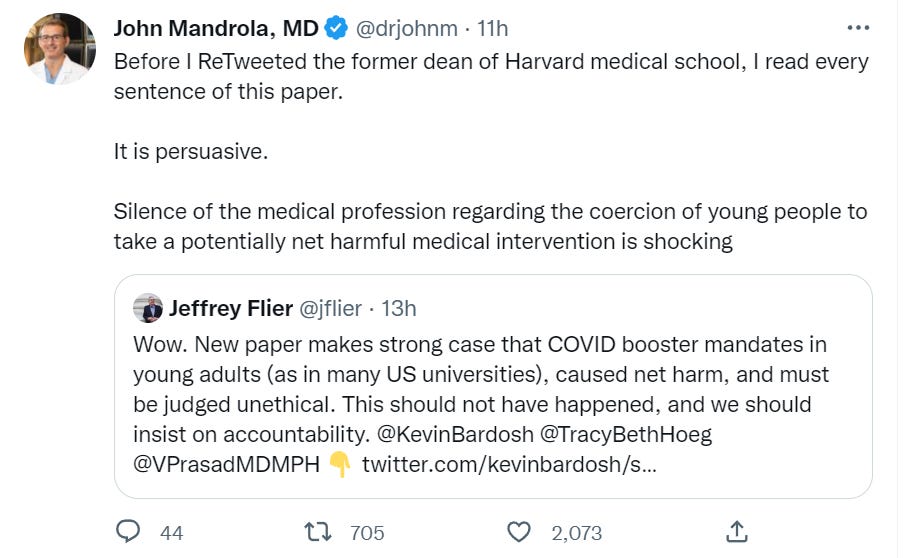

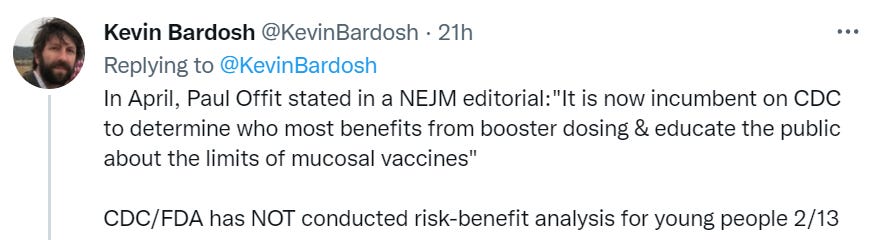

New paper finds that college vaccine mandates do more harm than good.

Here is a thread from one of the authors.

He then adds five ethical arguments against further mandates.

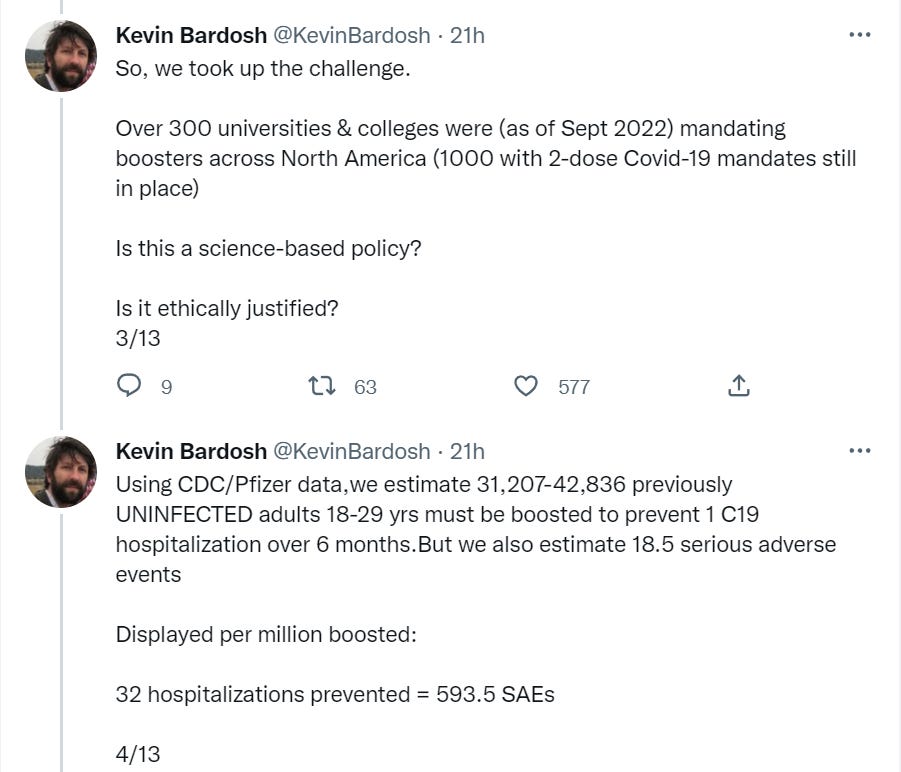

The emphasis on serious adverse events ignores the issue of non-serious adverse events. I remain skeptical of the claimed rare adverse events, but look at that NNT: something like 37,000 boosters per hospitalization prevented. Let us assume that, on average, a booster given to a random person knocks you on your ass for a day. That’s one hundred years, an actual lifetime, of knocked-on-ass time for every hospitalization prevented. The torture here seems less bad than the dust specs. You do have to also account for the time Covid would differentially do the on-ass-knocking as well, so it is not an entirely fair comparison, yet it seems telling.

Variants

Physical World Modeling

Study about the origins of the Omicron variant, and rather biting criticism thereof.

A worthwhile periodic reminder of what matters most for your health.

‘Bigger than genetics’ will always depend on the reference class. Still, we should remember that we endlessly obsess over other ‘risks’ to our health when by far the biggest preventable danger is a failure to get our basic house in order: Exercise, diet, healthy weight, social support, stress management, emergency savings, clean air, including a massive risk impact if you get Covid.

And yes, this is the same account that was talking about boosters and masks above.

Long Covid

Another example of how not to measure Long Covid, which in some ways is highly archetypical and I am telling myself this combined with getting it via a well-meaning source justifies Something Is Wrong On The Internet.

What did they actually ask?

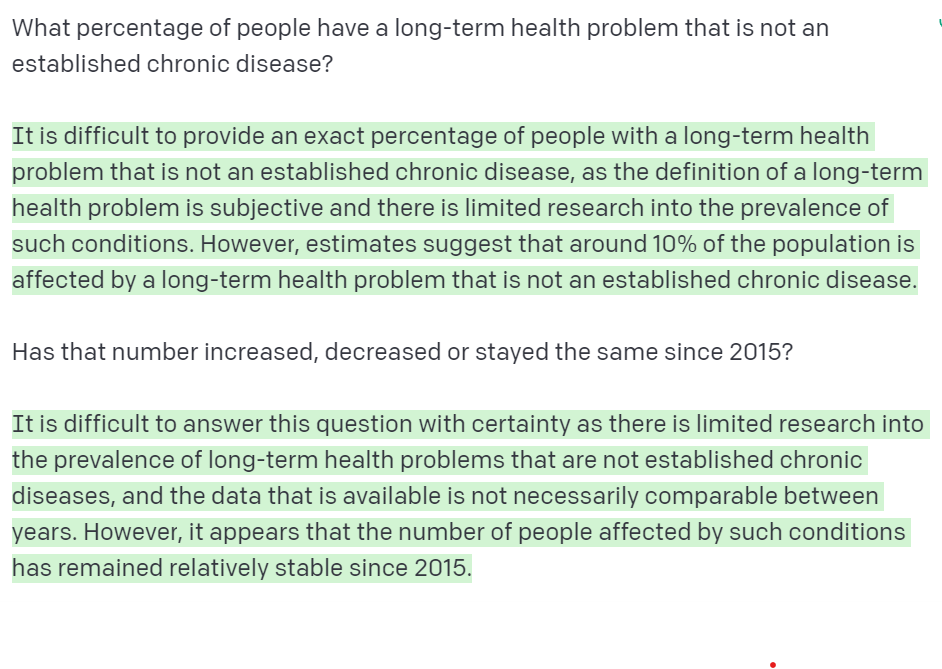

In other words, 14% of Swedish people have an undiagnosed chronic condition of some kind. I can totally believe that, because people often suffer from undiagnosed chronic conditions.

The methodology here seems to literally be ‘every undiagnosed chronic condition is Long Covid.’ And also that this is uniquely Swedish in magnitude as a result of Sweden’s sins against public health.

Fun with ChatGPT, by the way (note that its sources go up to September 2021), one-shot attempt and of course do not rely on this in any way for anything whatsoever:

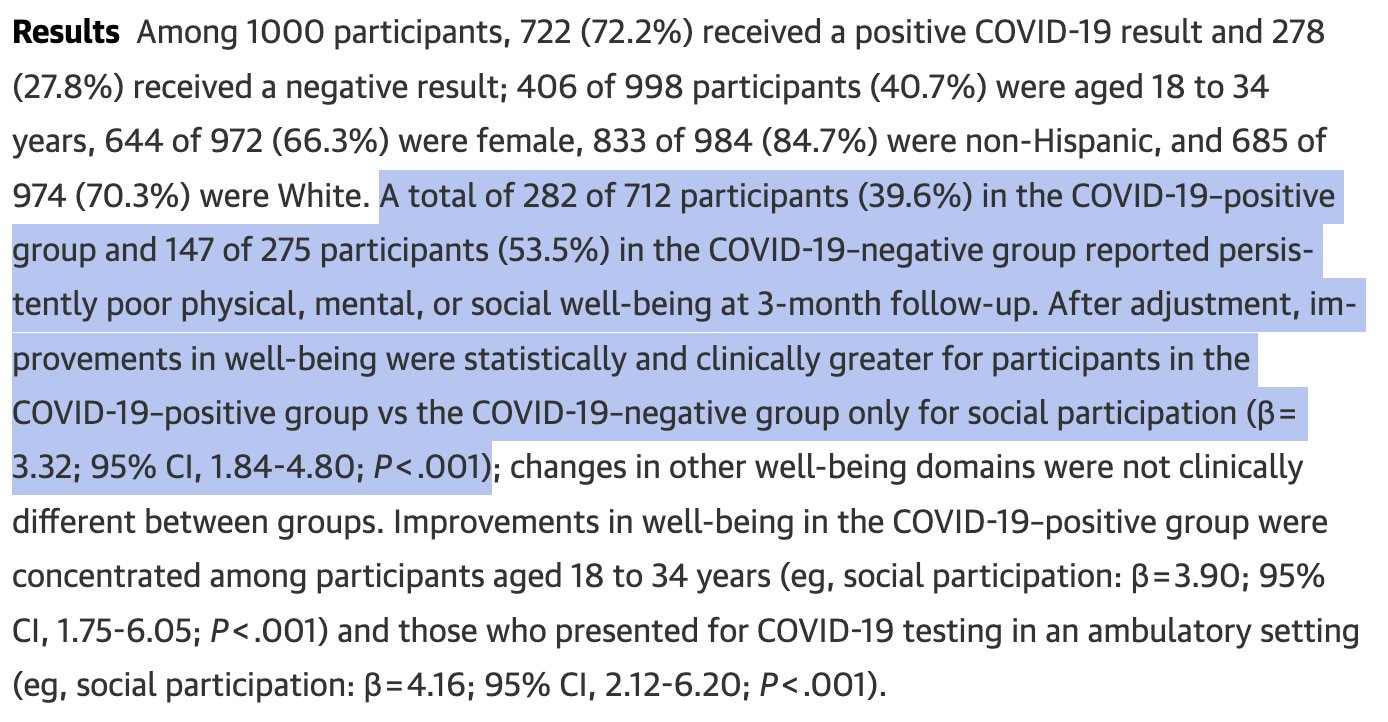

Then there is the flip side. Here’s an interesting Long Covid study (good analysis video, 9 min), where it is compared to other viruses.

Did this study have important limitations? Absolutely it did.

It is still a key reiteration of the central point of Long Covid, which is that

A lot of this is selection effects.

Long Infection is a thing across infections. Getting sick is not good for you.

We do not pay enough attention to Long Infection, but Long Covid is not special.

In Other Covid News

Permanent Midnight

You sound like #maskup #publichealth GPT edition.

We still hear this occasionally. Mostly we don’t, but only because such voices lost.

In other news, CDC goes back to recommending masks, at least temporarily. If one was going to recommend this some of the time while mostly not doing so, I do not think this is an unreasonable time to suggest that, given RSV and flu on top of Covid.

The latest update on the impact of Covid prevention measures on children (WaPo).

Something in particular struck me about the way a suffering student viewed things.

After that devastating stretch in May, families and classmates in the Chandler Unified School District mourned the three 15-year-olds. They would enjoy no more summer vacations, no birthdays or graduations.

Summer vacation is the ability to not go to school.

Graduation is the ability to not go to school.

Birthdays mark your progress towards not going to school.

There are two stories here.

In the wake of Covid prevention, our children face a mental health crisis.

Then again, they already faced a mental health crisis by reasonable standards.

If it’s not getting better now under normal conditions, what does that tell us?

A year later, this October, they sounded the alarm again. Things are not getting better.

…

Not long after the pandemic started, researchers began to document declines in child and adolescent mental health. The numbers are stark.

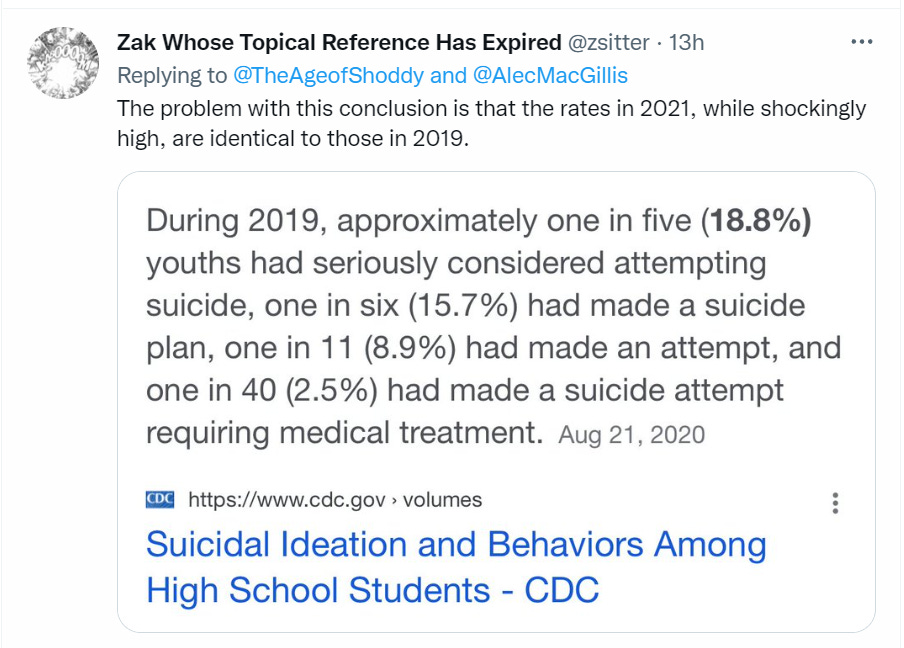

Are they, though? I followed a link in the post, to here.

The U.S. suicide rate resumed its upward climb in 2021 after two years of decline, with young people and men hit hardest by the persistent mental health crisis, according to provisional data released Friday by the government.

The 4 percent increase almost wiped out modest decreases in the two previous years, bringing the country back near the most recent peak in suicide deaths, 48,344 in 2018. There were 47,646 suicides in 2021, according to the data, boosting the rate to 14 per 100,000 people, up from 13.5 in 2020.

The increase was bigger among children, yet even in its peak relative increase (again in October, right after school starts up again) they only quote 11%. If 111% of previous levels of children killing themselves is a ‘crisis’ then why exactly is 100% of previous levels not a crisis? Is this out of line with what one would expect from the general and unavoidable ‘life is worse now’ that we experienced? And why aren’t things now getting better?

I think that our implementation of ‘remote learning’ made things dramatically worse for children. I also think that the core ongoing crisis has little to do with the pandemic and that officials are looking to use it a scapegoat.

Also, here’s how they think about your ‘mental health.’

School administrators across the country are clear-eyed about students’ worsening mental health, many of them strategizing about school initiatives that might help.

“We know that when kids are mentally well, they’re much more likely to attend school and do well in school,” said Sharon Hoover, co-director of the National Center for School Mental Health.

Ah, yes. That’s why child mental health is so important.

China

There was an Odd Lots podcast on the China protests. If you want more detail, it is recommended and is also self-recommending.

Here is a short CNN clip of what life is like in China, with constant Covid tests and code scans. Want to go to the McDonald’s and get pick-up, since no one can go in? Not so fast, we need to be sure.

The protests from last week made a big splash for a few days. What they could not do was sustain themselves for longer than that.

They likely still pushed things slightly more open than they otherwise would have been. Chinese officials have (I think wisely) long taken protests as a sign that a proportionate response is needed. So there have been some changes. Some people, for example, are being allowed to quarantine at home for the first time. You can go into more places without a PCR test.

Following up from last week, after his lockdown for being in a sports bar he was not at, Christian managed to go outside earlier than expected after his code went green on day four. Whole thing sounds like a confused mess that reflects a lower level of precaution.

Overall, how big are the changes?

Scott Gottlieb says not that big.

Small changes on the margin make a big difference, both to lived experiences and for potentially tipping Covid over the threshold where it is no longer contained. China can loosen impactfully only to the extent that they are making mistakes and taking essentially useless precautions, and they differentially identify those choices. I am confident there is some uselessness (such as with surfaces), what I still do not see is a new differentiation on the basis of effectiveness, only on the basis of responding to frustrations.

Monkeypox Redux: Total failure or a model response?

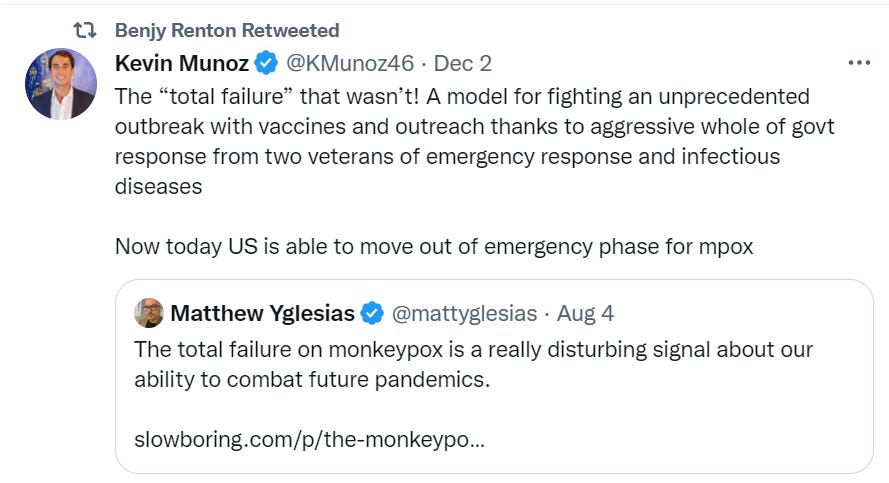

I say it was both, depending on your point of view.

The public health outcome was a great success. Cases peaked at a relatively low level, vaccinations happened, behaviors were modified and now the whole thing is mostly a distant memory.

A classic fallacy in public health is to equate the goodness of the outcome with the goodness of people’s actions (either in terms of public health’s version of morality, or in terms of the effectiveness of the actions, or a failure to realize there is a difference).

Public health can have a big impact on the margin while having little control over the grand arc of outcomes. The biology and physical facts, and the social and political dynamics, are what they are. Often, the difference between the best plausible response and a quite bad response is rather small, even if one can easily envision vastly different arcs of history. Or that most of our decisions did not in the end much matter, given initial conditions, and it all came down to one or a few big decisions. In the case of Covid, that would be Operation Warp Speed - both going fast and not going faster.

My model is that Monkeypox was one of those situations.

There was most certainly room for improvement. We could have been better with our messaging, focusing more on protecting everyone’s health, improved how we handled cases and suspected cases in terms of diagnosis and treatment, and improved our manufacturing and distribution of vaccines. We could have protected more of the people who most needed it, and done so faster.

If we had gotten the best possible response from public health once cases started happening, we would have peaked sooner with less cases, which would look broadly similar looking back. If we had gotten the best possible response including preparing for this very predictable scenario in advance then we would have had even less trouble. In percentage terms this could be noticeable. In absolute terms, mostly not.

There was also lots of room to have botched things more. We could have actively inflicted stigma. We could have so feared actively inflicting stigma that we didn’t get the vaccine or warnings to those who needed it at all, or did so much less, or attacked much more those who were trying to help. We could have had further delays or logistical failures. We could have simply ignored the problem.

What would the worst case scenario have been? Say we had ensured we would do nothing by deciding to attack those who tried to do anything about the problem as bigoted - a mistake that sadly February 2020 and other incidents make clear is well within our range. The vaccine doesn’t get distributed widely for a long time, or isn’t targeted. How bad would things have gotten? Certainly we would have had bigger problems than we saw. I still think that, given what we know now, the risk of sustained spread outside of the most vulnerable communities was always quite low, and that those communities were always going to respond to conditions on their own reasonably soon no matter what Official Public Health did. The worst case scenario is certainly worse, but not terribly worse, and not a full blown pandemic.

In this particular scenario the stakes turned out to be relatively low, the core outcomes predetermined, our worst fears never seriously in play.

Looking back, the question we must ask is, what if this had been a very different scenario?

Early on, we did not know that transmission was as difficult as it turned out to be. We got lucky, as we do every day with countless other potential infections, that this one additional virus ‘didn’t have what it takes’ in its current form. Change that basic fact, and there is only a narrow window where the response we did muster changes the outcome from out of control to within control.

If this had been a harder problem, ‘total failure’ would absolutely be the fair description of our response. Thus, I think it is most helpful to view our response here as a failure. Having this be typical of our expected future responses is unacceptable.

Our errors were clear. We knew (and still know) about the threat, yet our vaccine stocks were woefully inadequate, and what we did have we took too long to distribute. We worried too much about whether ‘help get the message to the people who need it’ was good for the people who needed it, and to far too great an extent let how things looked overrule the need to fix how things are.

The good news is that all of that is fixable. The bad news is that the narrative taking shape is that there is little we need to fix, and little interest in preventing future pandemics, and the collapse of FTX is going to make this that much harder to fix.

Other Medical and Research News

The CDC will be that much harder to fix with everyone working remotely.

Changes, such as the transition to a largely remote workforce and a ballooning bureaucracy, he said, made it “almost impossible to get anything done” in his later years at the agency.

All that remote work is also an important symptom of the CDC’s problems, on multiple levels. I agree it adds to the degree of difficulty, yet of a problem that was already next to impossible. Organizations like the CDC, that are long established with dysfunctional cultures that protect themselves against change, are mostly not fixable, you need to replace and start over or learn to live without. Without even the ability to be in the physical presence of the employees determined not to change and whom you mostly can’t fire and enjoy little leverage over, well, I wish everyone luck.

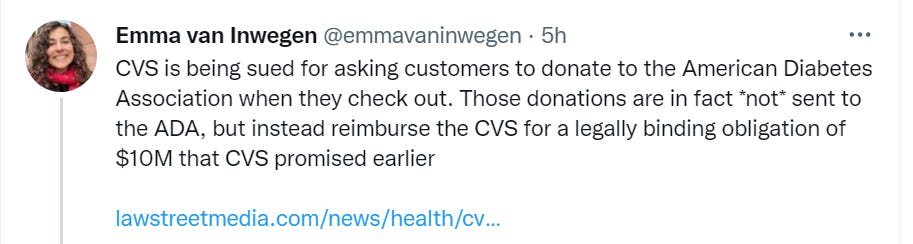

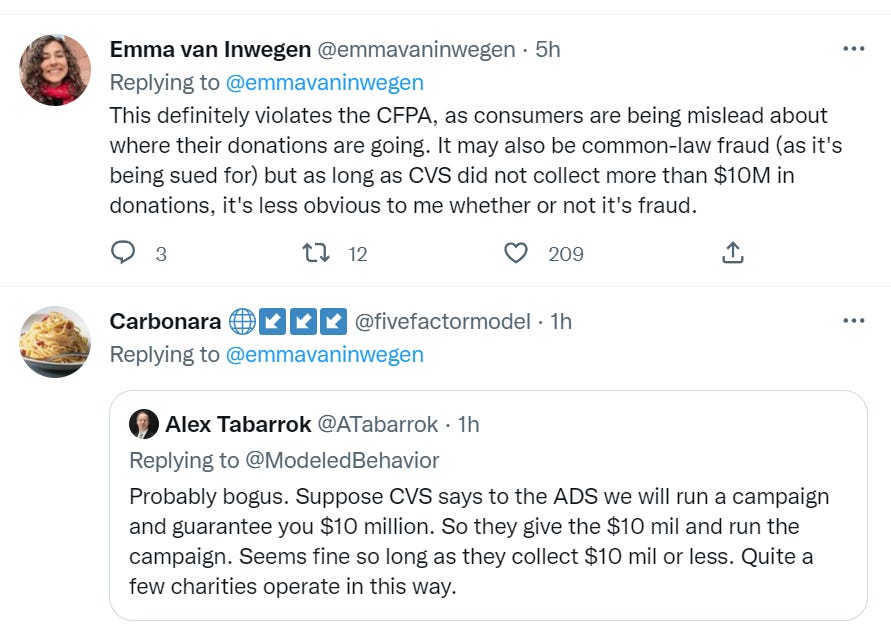

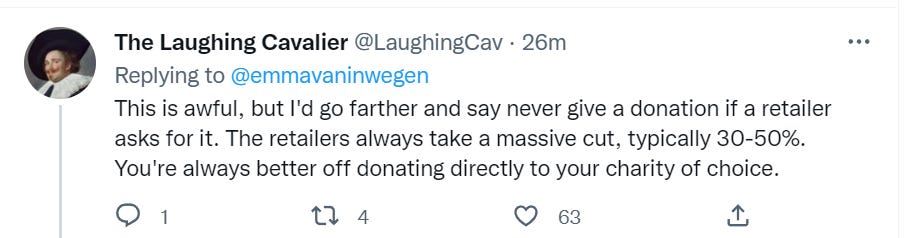

You know how every damn time you check out at CVS you have to click an extra time and perhaps feel a little bit bad because they ask you for a donation to the American Diabetes Association? These things fill me with rage on principle for taxing my time and cognitive function and occasionally tricking or guilting others, yet it is so much worse than that.

Thus: A public service announcement. Whenever any retailer asks you for a ‘donation’ to anything, you say no, and downgrade the ethics of the retailer and also the charity. Then, later, on the basis you think is best, decide if, where and how much to donate to charity.

Oh, great, an outbreak of measles, 50 kids in Ohio. Good news is 100% unvaccinated.

Texas rural hospitals (26%) at risk of closure, over a third have negative margins. The economics did not work before and even more do not work with newly increased labor costs.

What should you think when a study tells you sugar rushes aren’t real? In this case, Hadas reaches the conclusion that telling parents they aren’t real would be obnoxious, and also that it would not be good for sense-making. He does not then make the leap to this being because sugar rushes are real. Of course they are real. Most people have experienced them, this is not a subtle thing. If there is data to defy, I happily defy it.

I don't go around having arguments with strangers about this, but I have had a continuing discussion with my parents about the reality of "sugar rushes". According to my parents, when I was a child, I was _incredibly_ bad at handling sugar and they could immediately tell whether or not I had any. Of course, I was actually pretty good at sneaking candy, and they caught me in a pretty small minority of cases.

My view on the way that the science fits in with the lived experience of parents everywhere is that high sugar intake _usually_ occurs in very specific circumstances: birthday parties, sleep overs, etc. Those activities are likely to be high-excitement and lots of rambunctiousness going on. The perception is: child eats 1/2 of a birthday cake, then runs in circles until they fall over, and those things both happened, but the science says it's not related to the sugar. Luckily, we don't need to invalidate the experience of "child ran around like a maniac". That _did_ happen, it's just (in my opinion) more likely due to the environment in which the sugar was consumed rather than the sugar itself.

I did eventually learn to stop arguing with my parents about this (note: I'm far too old for it to be about regulating my own sugar content, more about discussions about parenting my own kids), or anyone else for that matter. It's too trivial, and people's opinions are too set on it.

Maybe my own experiences will change my mind in defiance of the data in the next few years. We will see.

"I think that our implementation of ‘remote learning’ made things dramatically worse for children."

And, this is important to realize, to a very large extent schools never went back to the pre-Covid procedures. Often they're just conducting remote learning with the students in the schools instead of at home.

It's a bit better because the teachers are on hand if the student has the initiative to ask a question. But it's not the way they were conducting classes pre-Covid.

If I had my choice, they'd take all those Chrome books and put them in a landfill somewhere, and go back to non-electronic learning again. Again and again I'm seeing this electronic learning model have problems for my son, who was a straight A student before Covid, and now struggles to maintain a mix of A's and B's. The electronic learning has inserted too many failure points that are unrelated to the actual academics.