Fertility Roundup #5: Causation

There are two sides of developments in fertility.

How bad is it? What is causing the massive, catastrophic declines in fertility?

What can we do to stabilize and reverse these trends to a sustainable level?

Today I’m going to focus on news about what is happening and why, and next time I’ll ask what we’ve learned since last check-in about we could perhaps do about it.

One could consider all this a supplement to my sequence on The Revolution of Rising Expectations, and The Revolution of Rising Requirements. That’s the central dynamic.

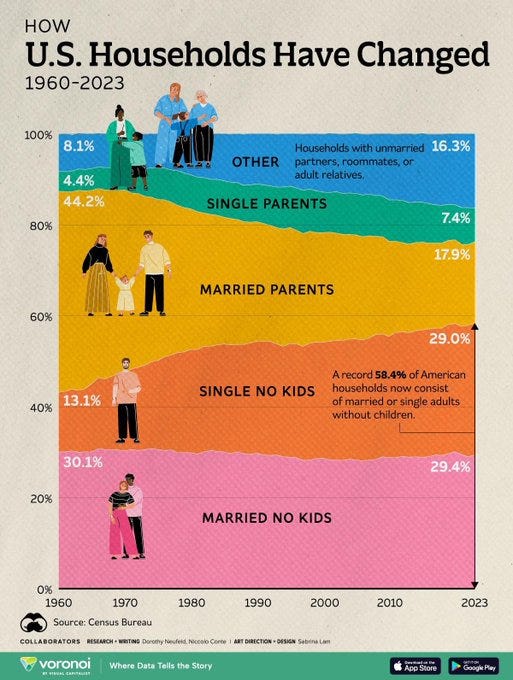

Household Composition

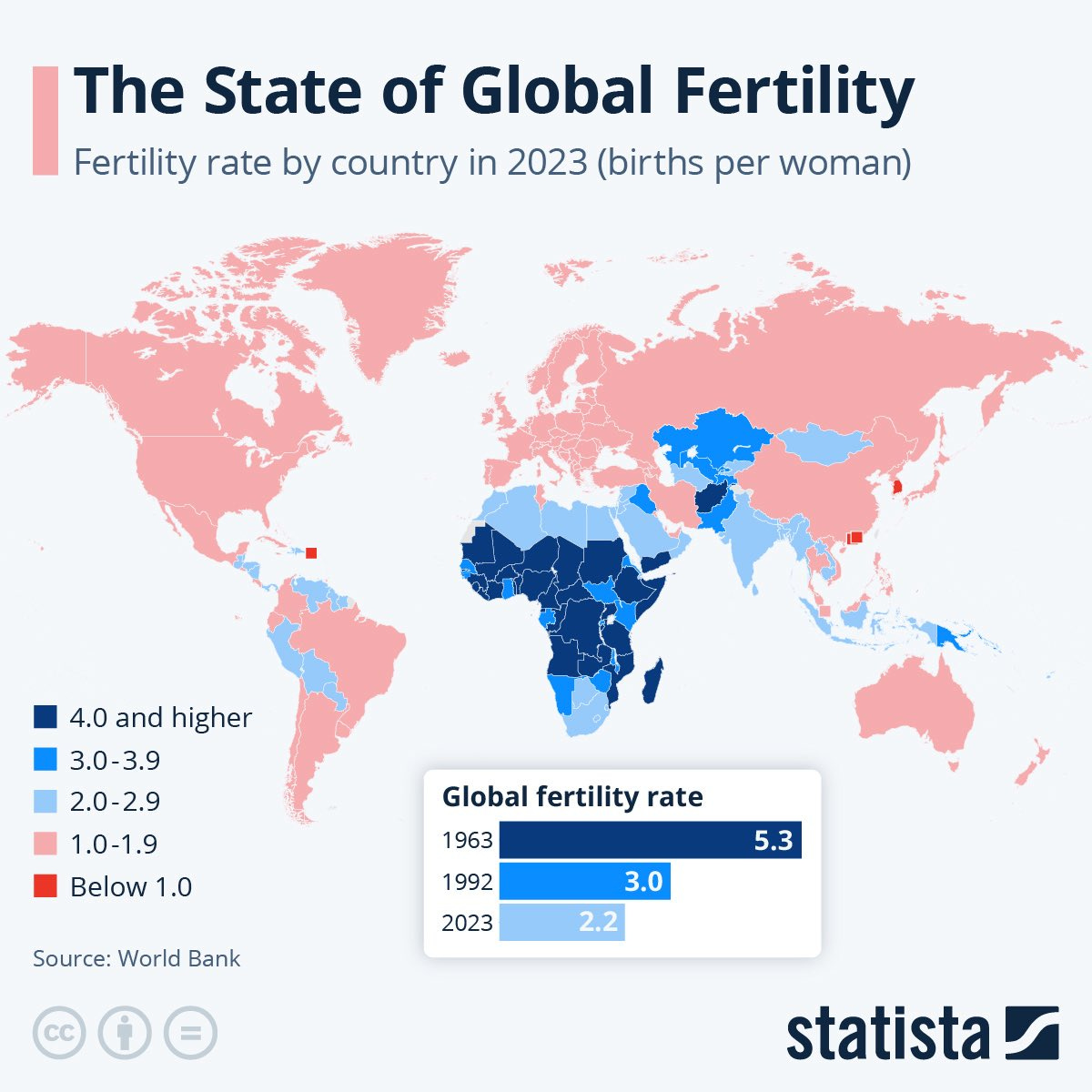

What is happening? A chart worth looking at every so often.

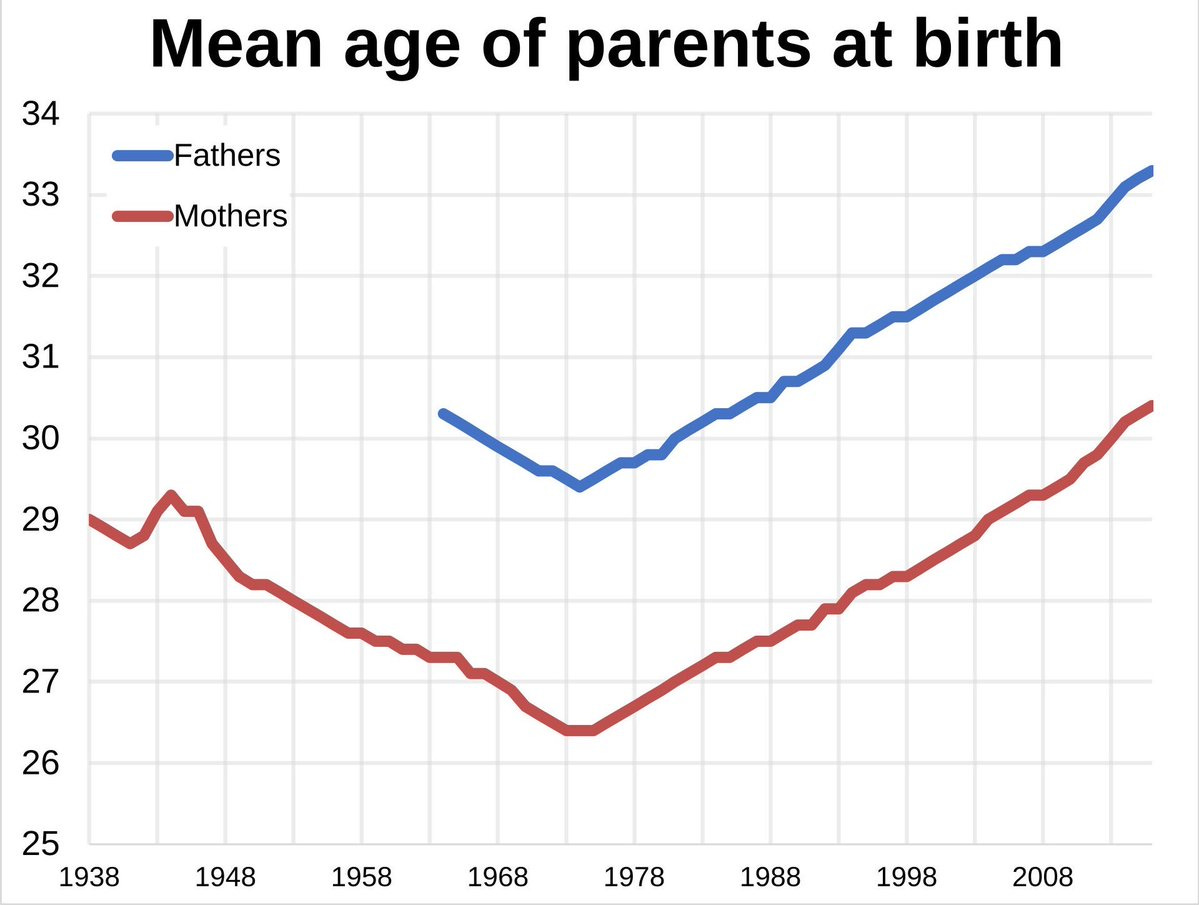

Timing

Michael Arouet: No way. WTF happened in 1971?

This is United States data:

The replies include a bunch of other graphs that also go in bad directions starting in 1971-73.

Developmental Idealism

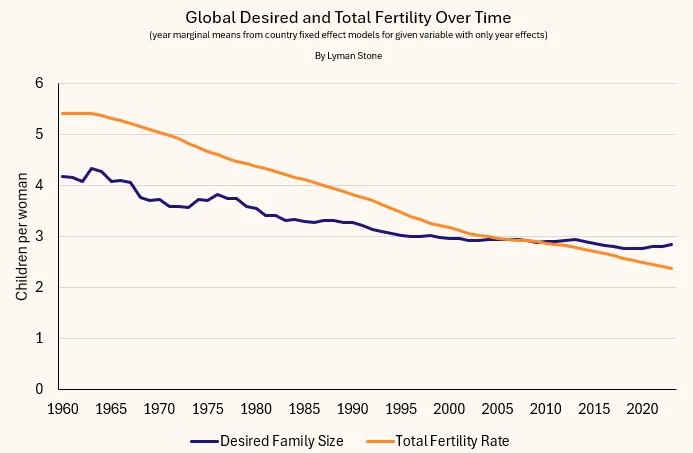

Lyman Stone, in his first Substack post, lays the blame for fertility drops in non-Western countries primarily on drops in desire for children, via individuals choosing Developmental Idealism.

Lyman Stone: Five Basic Arguments for Understanding Fertility:

Data has to be read “vertically” (longitudinally), not “sideways” (cross-sectionally)

No variable comes anywhere close to “survey-reported fertility preferences” in terms of ability to explain national fertility trends in the long run

People develop preferences through fairly well-understood processes related to expected life outcomes and social comparison

The name for the theory which best stands to explain why preferences have fallen is “developmental idealism.”

Countries with fertility falling considerably below desires are doing so primarily due to delayed marriage and coupling

TANGENTIALLY RELATED BONUS: Education reduces fertility largely by serving as a vector for developmental idealism in various forms, not least by changing parenting culture.

The central point of idea #1 is you have to look at changes over time, as in:

If you can tell Italy, “When countries build more low-density settlements, TFR rises,” that is orders of magnitude more informative than, “Countries with more low-density settlements have higher TFR.”

The first statement is informing policymakers about an actual potentiality; the second is asking Italy to become Nepal.

The overall central thesis:

“Falling child mortality means people don’t need to have as many kids to hit their family goals, and those family goals are themselves simply falling over time.”

…

Both actual and desired fertility have fallen since 1960, but actual fertility has fallen much more. The biggest reason for this is actual fertility is also influenced by child mortality, which has fallen a lot since 1960.

So in this model, the question becomes why are desired family sizes falling?

Lyman thinks this mostly comes down to comparisons with others (he explicitly doesn’t want to use the word ‘status’ here).

And his thesis is essentially that people around the world saw European wealth, found themselves ‘at the bottom’ of a brand-new social scale, and were told to fix this they had to Westernize, and Western culture causes the fertility decline.

This doesn’t explain where the Western desire for smaller families came from.

I also don’t think that this is why Western culture was adapted. I think Western culture is more attractive to people in various ways - it largely wins in the ‘marketplace of ideas’ when the decisions are up to individuals. Which I think is largely the level at which the decisions are made.

Pessimism

People’s severe pessimism, and inability to understand how good we have it, is making all these issues a lot worse.

Ben Landau-Taylor: Knowing a decent amount of history will cure lots of fashionable delusions, but none quite so hard as “How could anyone bring a child into a world as remarkably troubled and chaotic as the year 2025”.

Matt McAteer: Historical periods with names like “The Twenty Years’ Anarchy”, “The Killing Time”, “The Bronze Age Collapse”…or god forbid, “The Great Emu War”…2025 doesn’t seem so bad by comparison.

Nested 456: My mother grew up playing in bomb sites in northern England right after WW2. Really we’re spoiled brats in comparison

Are there big downsides and serious issues? Oh, definitely, atomization and lack of child freedoms and forms of affordability are big problems, and AI is a big risk.

Baby Boom

Saloni Dattani and Lucas Rodes-Guirao offer us a fun set of charts about the baby boom, but they don’t offer an explanation for how or why that happened, as Derek Thompson points out none of the standard explanations fully line up with the data. A lot of people seem to grasp at various straws in the comments.

Handy and Shester do offer an explanation for a lot of it, pointing to decline in maternal mortality, saying this explained the majority of increases in fertility. That is certainly an easy story to tell. Having a child is super scary, so if you make it less scary and reduce the health risks you should get a lot more willingness to have more kids.

Tyler Cowen sees this as a negative for a future baby boom, since maternal mortality is now low enough that you can’t pull this trick again. The opposite perspective is that until the Baby Boom we had this force pushing hard against having kids and people had tons of kids anyway, whereas now it is greatly reduced, so if we solve our other problems we would be in a great spot.

Paperwork

The paperwork issue is highly linked to the safety obsession issues, but also takes on a logic all its own.

As with car seat requirements, the obvious response is ‘that’s silly, people wouldn’t not have kids because of that’ but actually no, this stuff is a nightmare, it’s a big cost and stress on your life, it adds up and people absolutely notice. AI being able to handle most of this can’t come soon enough.

Katherine Boyle: We don’t talk enough about how many forms you have to fill out when raising kids. Constant forms, releases, checklists, signatures. There’s a reason why litigious societies have fewer children. People just get tired of filling out the forms.

The forms occasionally matter. But I’ve found you don’t have to fill out the checklists. Pro tip. Throw them away.

Blake Scholl: I was going to have more children but the paperwork was too much.

Sean McDonald: It’s shocking how many times I’ve been normied in the circumstance I won’t blindly sign a parent form. People will get like..actually mad if you read them.

Nathan Mintz: An AI agent to fill out forms for parents - will DM wiring information later.

Cristin Culver: It’s 13 tedious steps to reconfirm to my children’s school district that the 13 forms I uploaded last time are still correct. 🥵

Car Seats As Contraception

Back in 2022 I wrote an extended analysis on car seats as contraception. Prospective parents faced with having to change cars, and having to deal with the car seats, choose to have fewer children.

People think you can only fit two car seats in most cars. This drives behaviors remarkably strongly, resulting in substantial reductions in birth rates. No, really.

The obvious solution is that the extent of the car seat requirements are mostly patently absurd, and can be heavily reduced with almost no downsides.

It turns out there are also ways to put in three car seats, in many cases, using currently available seats, with a little work. That setup is still annoying as hell, but you can do it.

The improved practical solution is there is a European car seat design that takes this to four car seats across a compact. It can be done. They have the technology.

In an even stupider explanation than usual, the problem is that our crash test fixtures that we use cannot physically include a load leg, so we cannot test the four car seat setup formally, so we cannot formally verify that they comply with safety regulations.

Scarlet Astrorum: I know why we can’t have 4 kids to a row in the car and it’s a silly regulatory thing. Currently, US testing protocols do not allow crash testing of U.S. car seats that feature a load leg, similar to the British four-seater Multimac (pictured).

The crash test fixture itself is designed so it cannot physically include a load leg. The sled test fixture does not have a floor so there is no place to attach a load leg.

This means safe, multiple-kid carseats used widely in Europe can’t even be *evaluated* for safety- it’s not that they break US safety regulations, they just can’t even attach onto the safety testing sled, which is all seat (also pictured).

To test the 4-kid carseats which use a load arm, there are already functional test fixtures, like the ECE R129 Dynamic Test Bench, pictured here, which has a floor. We just need to add this as a testing option. Manufacturers could still test with the old sled.

What needs to change: 49 CFR § 571.213 s10.1-4 and Figure 1A which lock you in to testing with a floorless sled All that needs to change is updating the wording to clarify test positioning for a sled with a floor as well.

You would also have to spread the word so people know about this option.

You Can’t Afford It

Of course you are richer than we used to be, but not measured in the cost to adhere to minimal child raising standards, especially housing and supervision standards.

David Holz: i find it so strange when people say they can’t afford kids. your ancestors were able to afford kids for the last 300,000 years! are we *really* less wealthy now? you might think your parents were better off, but how about further back? they still went on.

Scarlet Astrorum: What people mean when they say this is often “I am not legally allowed to raise children the way my poor ancestors did”

Personally I only have to go back 2 generations to find behavior that I think is reasonable given circumstances but would be currently legally considered neglect

“I will not risk the custody of my existing children to raise more children than I can supervise according to today’s strict standards” is unfortunately a very reasonable stance. Of course, there are creative workarounds, but they are not uniformly available

Yes The Problem Is Often Money

Here is the latest popping up on my timeline of ‘how can anyone have kids anymore you need a spare $300k and obviously no one has that.’

That is indeed about what it costs to raise a child. If you shrink that number dramatically, the result would be very different, at least in America.

America has the unique advantage that we want to have children, and like this man we are big mad that we feel unable to have them, usually because of things fungible with money. So we should obviously help people pay for this public good.

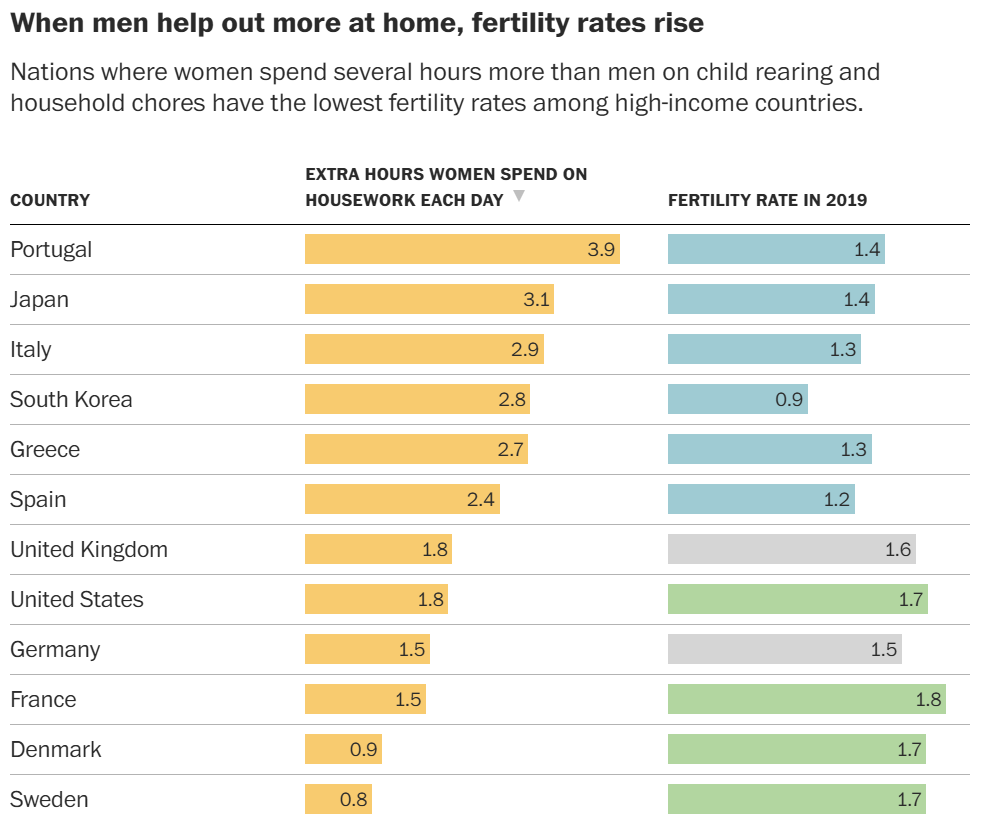

Housework

There is the housing theory of everything. Then there’s the housework theory of everything?

Heather Long: Goldin concludes that two factors explain much of the downward trend by country: the speed at which women entered the workforce after World War II, and how quickly men’s ideas about who should raise kids and tidy up at home caught up. This clash of expectations explains the fertility decline across the globe.

In places where men do more around the house, fertility rates are higher, where they do less, rates are lower.

Even the green bars are 1.7-1.8. That’s still below 2.1, even with a somewhat cherry-picked graph.

Also this is rather obviously not the right explanatory variable.

Why should we care about how many hours of housework a woman does more than the man, rather than the number of hours the woman does housework at all?

The suggestion from Goldin is more subsidized child care, but that has a long track record of not actually impacting fertility.

The actual underlying thing is, presumably, how hard it is on the woman to have children, in terms of both absolute cost - can you do it at all - and marginal cost versus not doing it. The various types of costs are, again presumably, mostly fungible.

The idea that ‘50-50’ is a magic thing that makes the work go away, or that it seeming fair would take away the barrier, is silly. The problem identified here is too much work, too many costs, that fall on the woman in particular, and also the household in general.

One can solve that with money, but the way to do it is simply to decrease the necessary amount of work. There used to be tons of housework because it was physically necessary, we did not have washers and dryers and dishwashers and so on. Whereas today, this is about unreasonable standards, and a lot of those standards are demands for child supervision and ‘safety’ or ‘enrichment’ that simply never happened in the past.

Greedy Careers

If market labor has increasing returns to scale, then taking time off for a child is going to be expensive in terms of lifetime earnings and level of professional advancement. Ruxandra’s full article is here, I quote mostly from her thread.

Ruxandra Teslo: One’s 30s are a crucial period for professional advancement. Especially in so-called “greedy careers”: those where returns to longer hours are non-linear.

But one’s mid 30s is also when most women’s fertility starts to drop.

In this piece, I lay out how a large part of the “gender pay gap” is just this: a motherhood pay gap. And, as Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin points out, this is particularly true in high-stakes careers like business, law, medicine, entrepreneurship and so on.

This reduction in earnings is not just about money either: it’s about general career advancement and personal satisfaction with one’s profession. Time lost in one’s 30s is hard to recuperate from later on.

In law, for example, one’s 30s is when the highest levels of salary growth take place. Founders who launch unicorns (startups worth more than a billion dollars) have a median age of 34 when they found their companies. In academia, one’s thirties are usually the time when a researcher goes through a string of high-pressure postdoctoral positions in an attempt to secure an independent position.

Aware of this, women delay pregnancy until they have advanced in their careers as far as possible. This is especially true for women w/ professional degrees. Women without a bachelor’s degree tend to have 1 to 1.5 children on ~ by age 28, while those with higher educational attainment have around 0.25 children by same age.

Highly educated women attempt to catch up during their 30s, with their birth rates increasing more rapidly. However, this compensatory period is limited, as fertility rates across all education levels tend to plateau around age 39. Thus, the educated group ends up with less kids.

The chance of conceiving a baby naturally with regular sex drops from 25 percent per month in one’s twenties to about five percent per month at 40, while the chance of miscarrying rises from about eight percent for women under 30 to around one in three for 40-year-olds.

[thread continues and morphs into discussing technological fertility solutions]

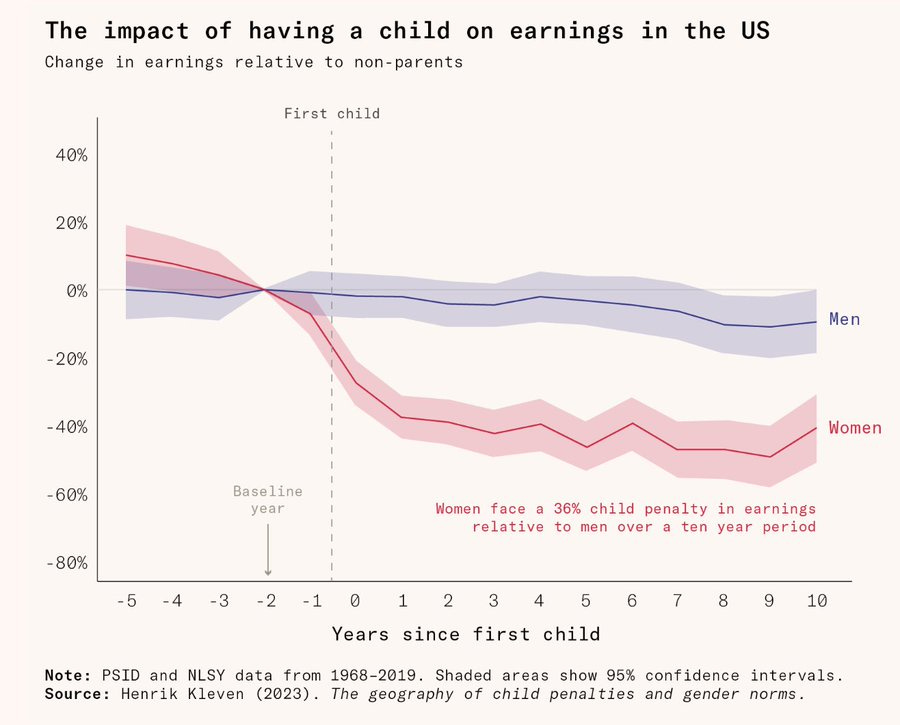

From Her Article: Women know this gap exists and plan accordingly: in countries where the motherhood penalty is keenest, the birth rate is lower.

…

We have come a long way from the explicit sex discrimination of the past. Today, the gap is primarily driven by the career toll exacted by motherhood.

A lot of the problem is our inability to realistically talk and think about the problem. There’s no solution that avoids trading off at least one sacred value.

The Appeal of Child-Free

It’s definitely super annoying that when you have kids you have to earn your quiet. This both means that you properly appreciate these things, and also that you understand that they’re not that important.

Hazal Appleyard: When you watch stuff like this as a parent, you realise how truly empty and meaningless all of those things are.

Destind for Manifest: “I don’t want children because it would keep me away from my favorite activities which are watching cartoons, doing silly hand gestures and taking videos of my daily life, all while keeping an exaggerated smile on my face at all times”

Literally the perfect momYashkaf: your life isn’t child-free. you *are* the child

no one’s making “my child-free life” content about using the spare 6 hours each day to learn some difficult skill or write a book or volunteer at a hospice

it’s always made by people who don’t seem to have plans, goals, or attention spans longer than an hour

Motivation

I too do not see this as the message to be sending:

Becoming a parent also makes it extremely logistically tricky to go to the movies, or to go out to dinner, especially together. Beyond that, yes, obviously extremely tone deaf.

The basic principle here is correct, I think.

Which is, first, that most people have substantial slack in their living expenses, and that in today’s consumer society your expenses will expand to fill the funds available but you’d probably be fine spending a lot less. Digital entertainment in particular can go down to approximately free if you have the internet, and you’ll still be miles ahead of what was available a few years ago at any price.

And second, that if you actually do have to make real sacrifices here, it is worth doing that, and historically this was the norm. Most families historically really did struggle with material needs and make what today would seem like unthinkable tradeoffs.

Also third, although she’s not saying it here, that not being able to afford it now does not mean you can’t figure it out as you go.

Amanda Askell: My friends just had a baby and now I kind of want one. Maybe our species procreates via FOMO.

I have bumped up the dating value of aspiring stay at home partners accordingly, on the off chance that I ever encounter one.

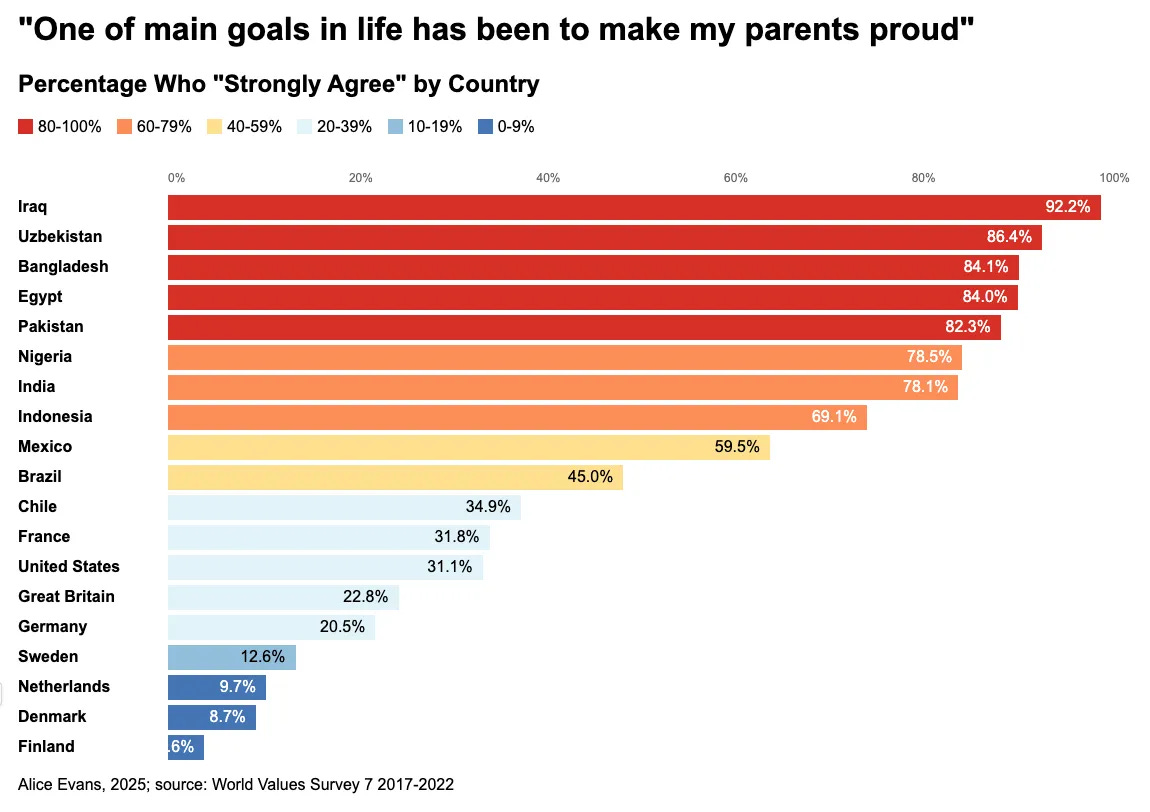

Another key form of motivation is, what are you getting in return for having kids? In particular, what will your kids do for you? How much will they be what you want them to be? Will they share your values?

The post mostly focuses on the various ways Indian parents shape the experiences of their children including getting transfers of resources back from them but mostly about upholding cultural and religious traditions, and how much modernity is fraying at that. For many, that takes away a strong reason to have kids.

Grandparents

The New York Times put out an important short article that made people take notice, The Unspoken Grief of Never Becoming a Grandparent.

Robert Sterling: I know a huge number of people in their 60s and 70s with one grandchild at most. Many with zero.

These people had 3-4 kids of their own, and they assumed their kids would do the same. They planned for 10-15 grandkids at this age.

Not for me to judge, but it’s sad to see.

I have little doubt that those considering having kids are not properly taking into account the grandparent effect, either for their parents or in the future for themselves.

Throughout, the frame is ‘of course my children should be able to make their own choices about whether to have kids,’ and yes no one is arguing otherwise, but this risks quickly bleeding into the frame of ‘no one else’s preferences should factor into this decision,’ which is madness.

It also frames the tragedy purely in experiential terms, of missing out on the joy and feeling without purpose. It also means your line dies out, which is also rather important, but we’ve decided as a society you are not allowed to care about that out loud.

Mason: I really hope I am able to say whatever I need to say and do whatever I need to do for my children to have some grasp of what a complex and transcendent joy it is to bring a new person into the world.

My daughter’s great-grandfather is dying at hospice. He is not truly present anymore.

Even when he was able to first meet her, he was not always fully there.

But a few times he did recognize me, so he knew who she was, and he would not eat so that he could just watch her toddle around.

I do not know how to explain it, man. At the very end, when you barely even remember who you are, the newest additions to your lineage hold you completely spellbound.

He would just stare at her and say, “She never even cries,” over and over, so softly.

The flip side is that parents, who are prospective grandparents, seem unwilling to push for this. Especially tragic is when they hoard their wealth, leaving their kids without the financial means to have kids. There is an obviously great trade for everyone - you support them financially so they can have the kids they would otherwise want - but everyone is too proud or can’t admit what they want or wants them to ‘make it on their own’ or other such nonsense.

Audrey Pollnow has extensive thoughts.

I appreciated this part of her framing: Having kids is now ‘opt-in,’ which is great, except for two problems:

We’ve given people such high standards for when they should feel permission to opt-in. Then if they do go forward anyway, it is common to mostly refuse to help.

Because it is opt-in, there’s a feeling that the kids are therefore not anyone else’s responsibility, only the parents, at least outside an emergency. Shirking that responsibility hurts the prospect of having grandparents, as any good or even bad decision theorist knows, and thus does not improve one’s life or lineage.

I do not agree with her conclusion that therefore contraception, which enables us to go to ‘opt-in,’ is bad actually. That does not seem like the way to fix this problem.

Expectations of Impossibility

On top of how impossible we’ve made raising kids, and then we’ve given people the impression it’s even more impossible than that.

Potential parents are also often making the decision with keen understanding of the downsides but not the upsides. We have no hesitations talking about the downsides, but we do hesitate on the upsides, and we especially hesitate to point out the negative consequences of not having kids. Plus the downsides of having kids are far more legible than the benefits of kids or of the downsides of not having kids.

Zeta: crying in a diner bathroom because life has no end goal or meaning, the one person who feels like family is as unhappy as you are, you can’t eat bread, you kinda want kids but every time you spend time with other people’s kids it seems waaayyyy too high maintenance, your elderly parents/your only real home are fading and close to death as are impossibly young kids with weird-ass cancers that should be solvable but humans fuck it up and what is even the point of anything

I don’t know how parents do it, like I get excited to have kids purely as a genetics experiment and then I spend time with them and it’s non-stop chores which are tedious and boring like with a puppy but also not chill like a puppy because it’s a future human but you can’t talk to them about mass neutrophil death in bone formation when they ask questions that necessitate it

also I know I don’t believe in academia or science but I need to believe in something - like I need someone to let me rant about what we know for sure in development- otherwise it’s just a chaotic mass of noise hurtling towards a permanent stop just as turbulent and meaningless as the start

eigenrobot: there’s a lot of that but you kinda stop noticing it because there’s a lot of this too

Mason: Kids are hard but they are 100% better than this, the “what’s even the point” malaise that a lot of us start to feel because we are people who are meant to be building families and our social infrastructure was ill-suited to get everyone to do it in a timely fashion

I don’t know if it’s a blackpill or a whitepill, but I do think you have to pick your poison a little bit here

Kids will overwhelm you and deprive you of many comforts for a time, life without them may gradually lead you to become a patchwork of hedonistic copes

Again I struggle to explain the “upside” of parenthood bc it doesn’t lend itself to tabulation. I don’t just *like* my kids, they are the MOST everything. They are little glowing coals in a cold and uncaring universe. I hold that dear when I am cleaning the poop off the walls

Isolation

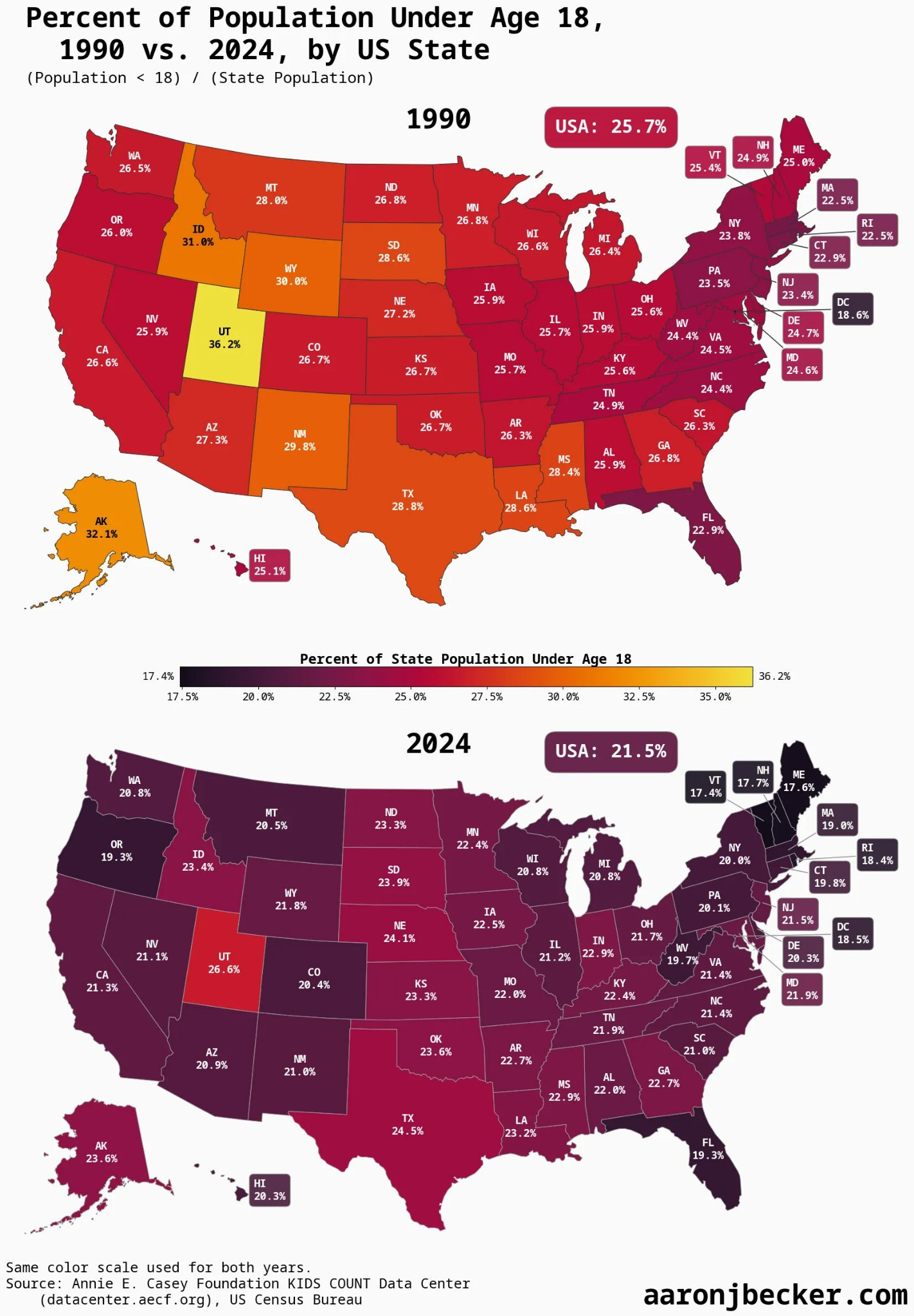

The shading here makes it look a lot more dire than it is, but yes a lack of other kids makes it tougher to have or decide to have your own.

Mason: 50 years ago, about 1 in 3 of the people around you were children. Now it’s about 1 in 5. That makes a huge difference when it comes to the availability of infrastructure for kids, convenient playmates, family activities.

For a lot of young people, parenting just looks isolating.This is one of the underappreciated ways a population collapse accelerates: when fewer people have kids, fewer people in the age cohort behind them see what it’s like having kids, and it just seems like a strange thing that removes you from public life and activities.

That’s one reason I think the (fraction of) pronatalists who advocate excessive use of childcare to make parenting less disruptive to their personal lives are counterproductive to their cause.

Constantly trying to get away from your kids to live your best life sends a message.n an ideal world, most adults have some kids, and society accomodates them to a reasonable degree because it wants their labor and their money

Unofficial kid zones pop up everywhere, indoors and out. Low-supervision safety features are standard to the way things are built.

The first best solution is different from what an individual can do on the margin.

I see the problem of childcare as not ‘the parents are spending too little time with the kids’ but rather ‘we require insane levels of childcare from parents’ so the rational response is to outsource a bunch of that if you can do it. The ideal solution would be to push back on requiring that level of childcare at all, and returning to past rules.

Decoupling

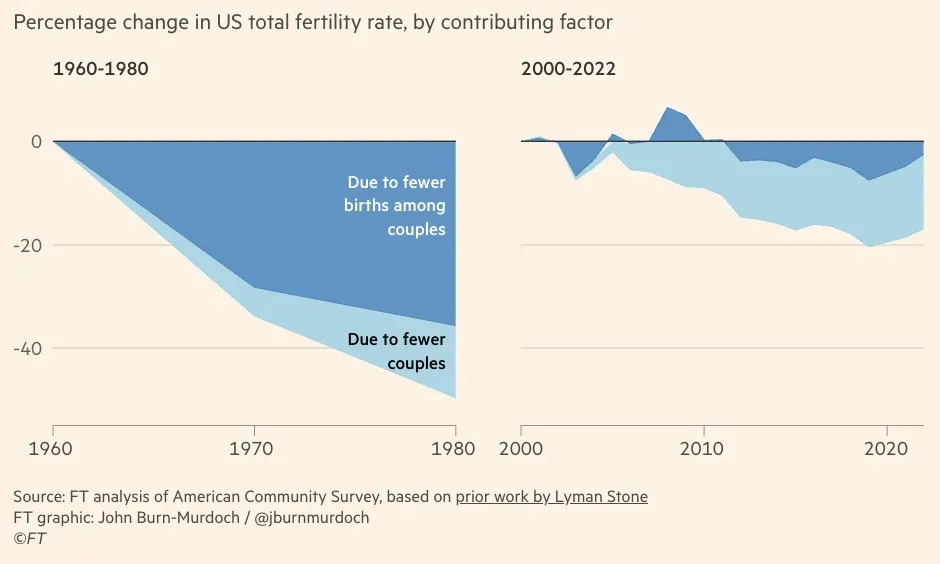

Alice Evans notes that unlike previous fertility declines, in the United States the recent decline is almost entirely due to there being fewer couples, while children per couple isn not changed.

This is at least a little misleading, since desire to have children is a major cause of coupling, and marginal couples should on average be having fewer children. But I do accept the premise to at least a substantial degree.

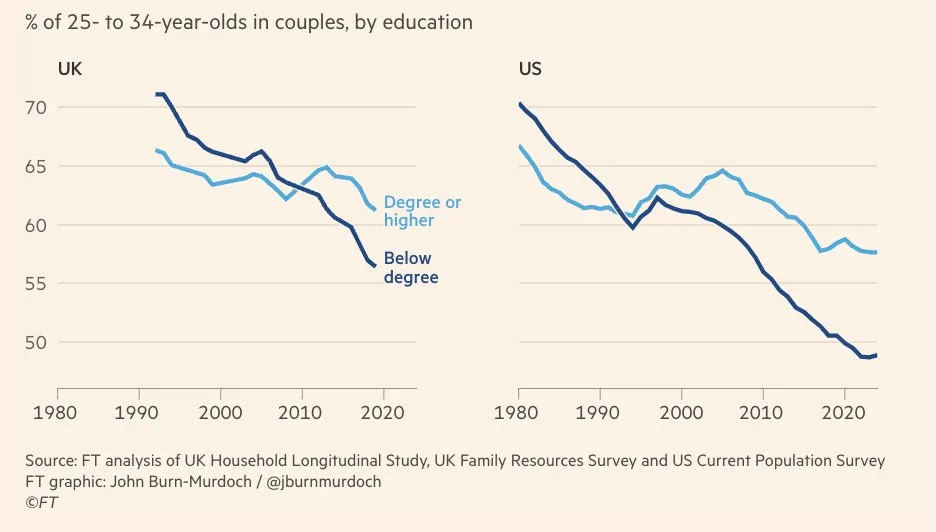

Also noteworthy is having less education means a bigger decline:

This is happening worldwide, and Alice claims it corresponds with the rise in smartphones. For America I don’t see the timing working out there? Seems like the declines start too early.

Then she turns to why coupling is plummeting in the Middle East and North Africa.

The first explanation is that wives are treated rather horribly by their in-laws and new family, which I can totally see being a huge impact but also isn’t at all new? And it’s weird, because you wouldn’t think a cultural norm that is this bad for your child’s or family’s fertility would survive for long, especially now with internet connectivity making everyone aware how crazy it all is, and yet.

It’s so weird, in the age of AI, to see claims like “The decline of coupling and fertility is the greatest challenge of the 21st century.”

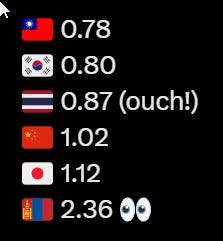

South Korea

This framing hit home for a lot of people in a way previous ones didn’t.

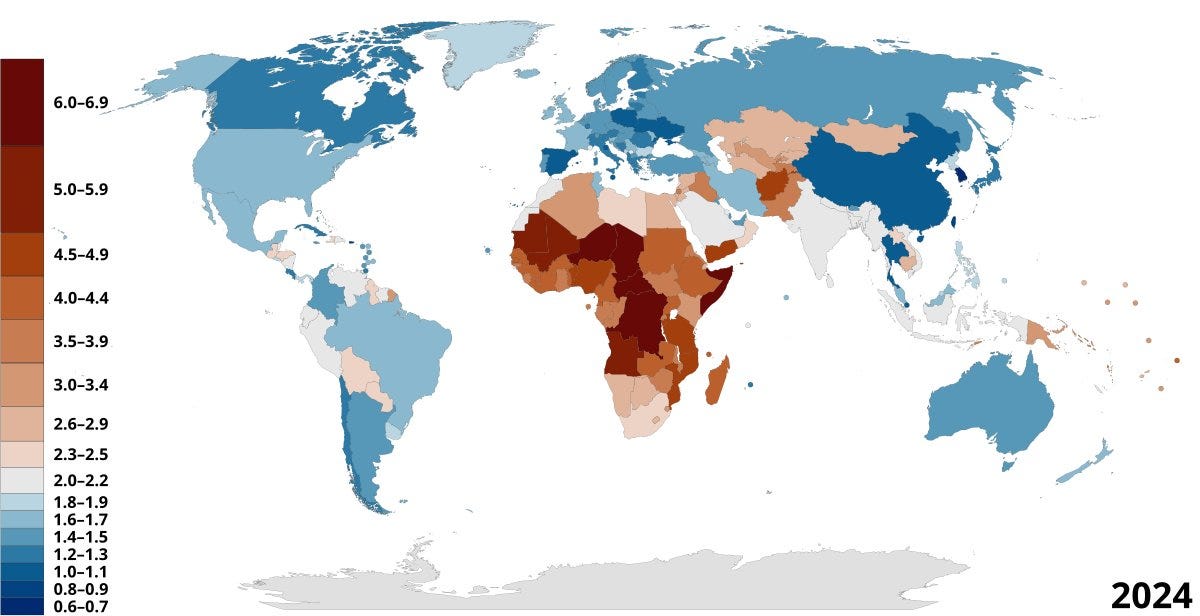

Camus: South Korea is quietly living through something no society has ever survived: a 96% population collapse in just four generations — with zero war, zero plague, zero famine.

100 people today → 25 children → 6 grandchildren → 4 great-grandchildren.

That’s it. Game over for an entire nation by ~2125 if fertility stays where it is (0.68–0.72).

No historical catastrophe comes close:

- Black Death killed ~50% in a few years

- Mongol invasions ~10–15% regionally

- Spanish flu ~2–5% globally

South Korea is on pace to lose 96% of its genetic lineage in a single century… peacefully.

We shut down the entire world for a virus with 1–2% fatality.

This is 96% extinction and the silence is deafening.

Japan, Taiwan, Italy, Spain, Singapore, Hong Kong, Poland, Greece — all following the same curve, just 10–20 years behind.

Robots, AI and automation might mitigate the effects along the way and prevent total societal collapse for a while, but there would soon be no one left to constitute the society. It would cease to exist.

It’s so tragic that a lot of this is a perception problem, where parents think that children who can’t compete for positional educational goods are better off not existing.

Timothy Lee: Parenting norms in South Korea are apparently insane. American society has been trending in the same direction and we should think about ways to reverse this trend. The stakes aren’t actually as high as a lot of parents think they are.

Phoebe Arslanagic-Little (in Works in Progress): South Korea is often held up as an example of the failure of public policy to reverse low fertility rates. This is seriously misleading. Contrary to popular myth, South Korean pro-parent subsidies have not been very large, and relative to their modest size, they have been fairly successful.

… In South Korea, mothers’ employment falls by 49 percent relative to fathers, over ten years – 62 percent initially, then rising as their child ages. In the US it falls by a quarter and in Sweden by only 9 percent.

South Koreans work more hours – 1,865 hours a year – in comparison with 1,736 hours in the US and 1,431 in Sweden. This makes it hard to balance work and motherhood, or work and anything else.

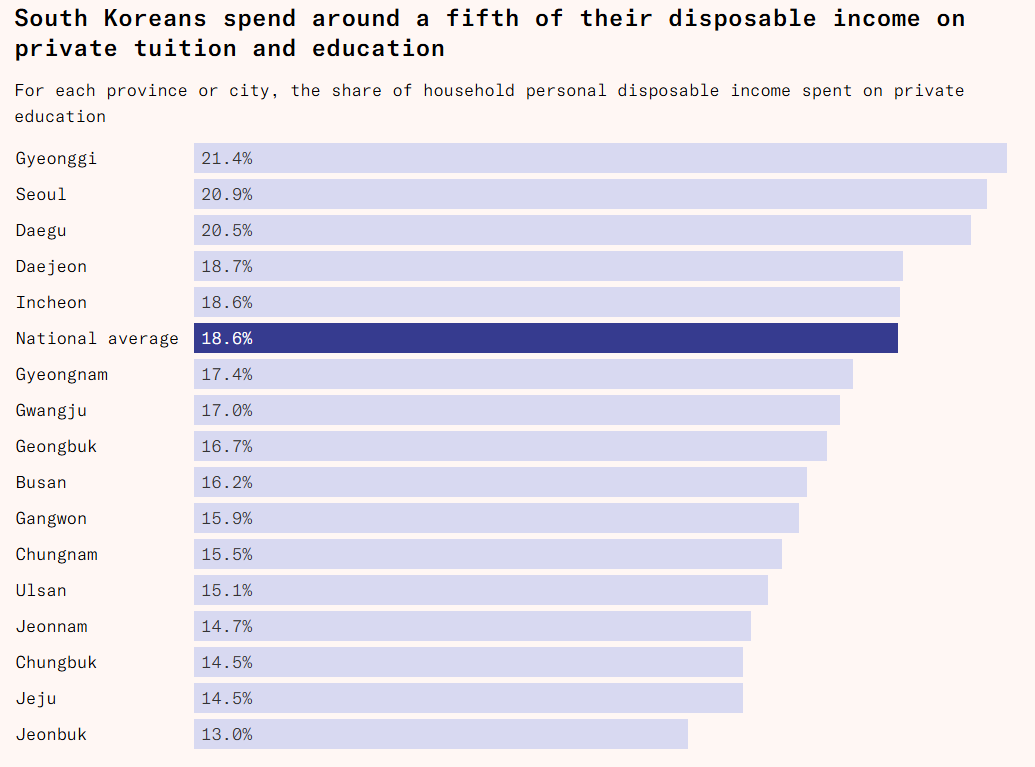

… Today, South Korea is the world’s most expensive place to raise a child, costing an average of $275,000 from birth to age 18, which is 7.8 times the country’s GDP per capita compared to the US’s 4.1. And that is without accounting for the mother’s forgone income.

… But South Korea is even worse. Almost 80 percent of children attend a hagwon, a type of private cram school operating in the evenings and on weekends. In 2023, South Koreans poured a total of $19 billion into the shadow education system. Families with teenagers in the top fifth of the income distribution spend 18 percent ($869) of their monthly income on tutoring. Families in the bottom fifth of earners spend an average of $350 a month on tutoring, as much as they spend on food.

Because most students, upon starting high school, have already learned the entire mathematics curriculum, teachers expect students to be able to keep up with a rapid pace. There’s even pejorative slang for the kids who are left behind– supoja – meaning someone who has given up on mathematics.

The article goes on and things only get worse. Workplace culture is supremely sexist. There’s a 1.15:1 male:female ratio due to sex selection. Gender relations have completely fallen apart.

The good news is that marginal help helped. The bad news is, you need More Dakka.

Every South Korean baby is now accompanied by some $22,000 in government support through different programs over the first few years of their lives. But they will cost their parents an average of roughly $15,000 every year for eighteen years, and these policies do not come close to addressing the child penalty for South Korean mothers.

… For each ten percent increase in the bonus, fertility rates have risen by 0.58 percent, 0.34 percent, and 0.36 percent for first, second, and third births respectively. The effect appears to be the result of a real increase in births, rather than a shift in the timing of births.

Patrick McKenzie: I don’t think I had clocked “The nation we presently understand to be South Korea has opted to cease existing.” until WIP phrased baked-in demographic decline in the first sentence here.

Think we wouldn’t have many lawyers or doctors if we decided “Well we tried paying lawyers $22k once, that didn’t work, guess money can’t be turned into lawyers and that leaves me fresh out of ideas.”

If you ask for a $270k expense, and offer $22k in subsidy, that helps, but not much.

The result here is actually pretty disappointing, and implies a cost much larger than that in America. The difference is that in America we want to have more kids and can’t afford them, whereas in South Korea they mostly don’t want more kids and also can’t afford them. That makes it a lot harder to make progress purely with money.

It’s plausible that this would improve with scale. If the subsidy was $30k initially and then $15k per year for 18 years, so you can actually pay all the expenses (although not the lost time), that completely changes the game and likely causes massive cultural shifts. The danger would be if those funds were then captured by positional competition, especially private tuition and tutoring, so you’d need to also crack down on that in this cultural context. My prediction is if you did both of those it would basically work, but that something like that is what it would take.

2024 was the first year since 2015 that total births increased in South Korea, by 3.1%, which of course is not anything remotely like enough.

Robin Hanson points us to this article called The End of Children, mostly highlighting the horror show that is South Korea when it comes to raising children.

Timothy Taylor takes a shot at looking for why South Korea’s fertility is so low, nothing I haven’t covered before. I’m increasingly leading to ‘generalized dystopia’ as the most important reason, with the mismatch of misogyny against changing expectations plus the tutoring costs, general indebtedness and work demands being the concrete items.

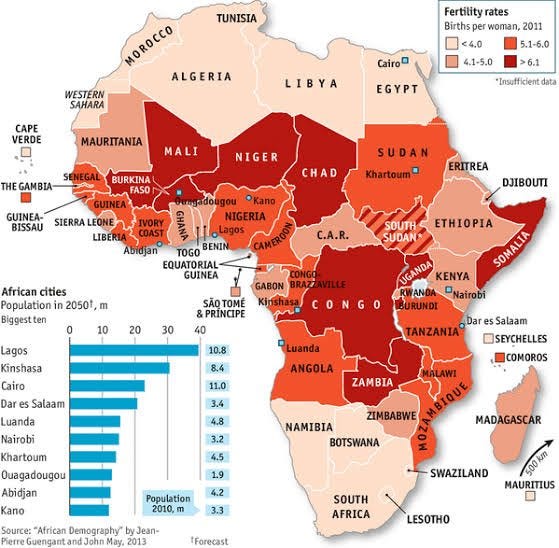

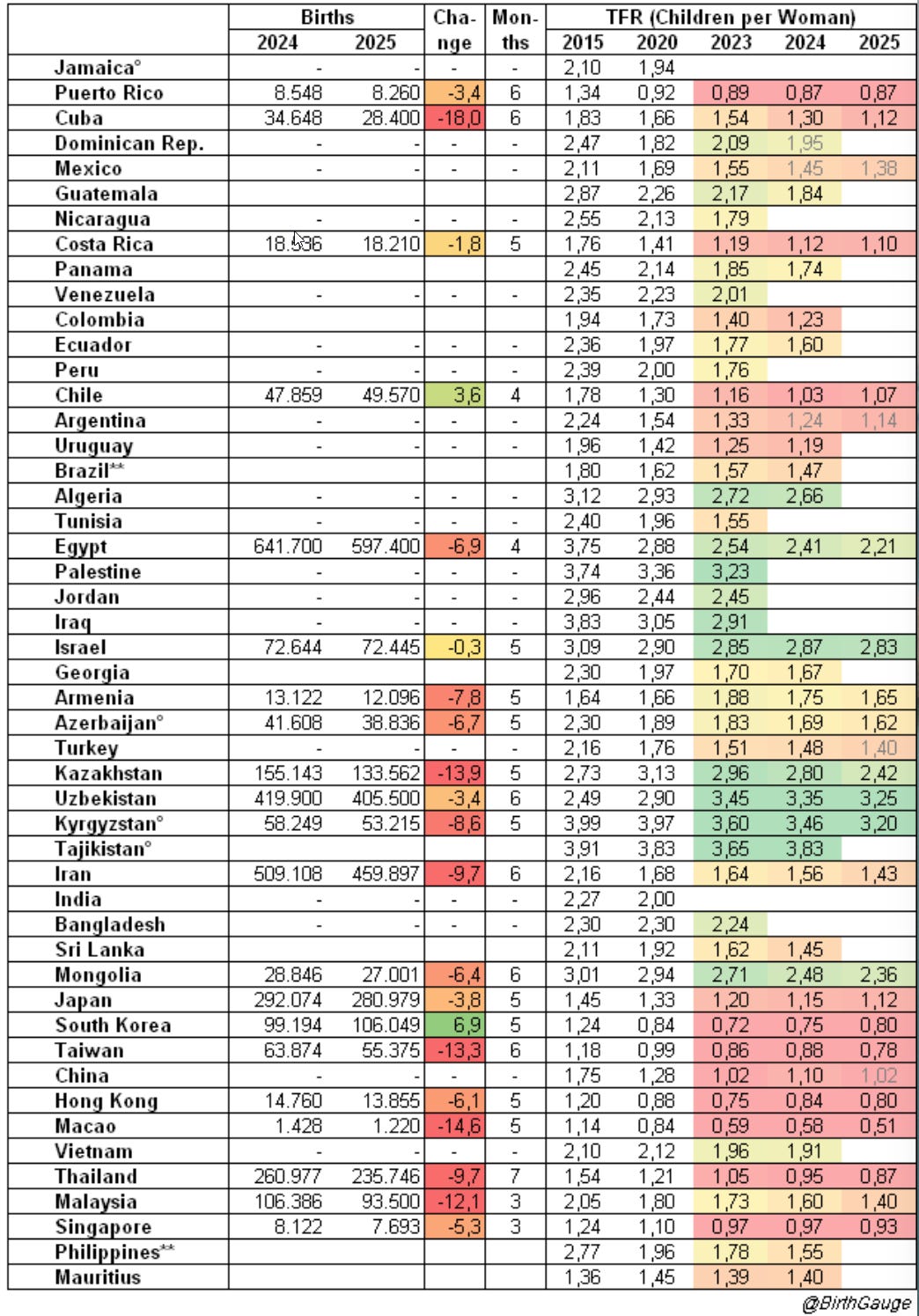

World

Various Places in Trouble

Angelica: Brutality. Taiwanese TFR fell below South Korea thus far 2025.

China

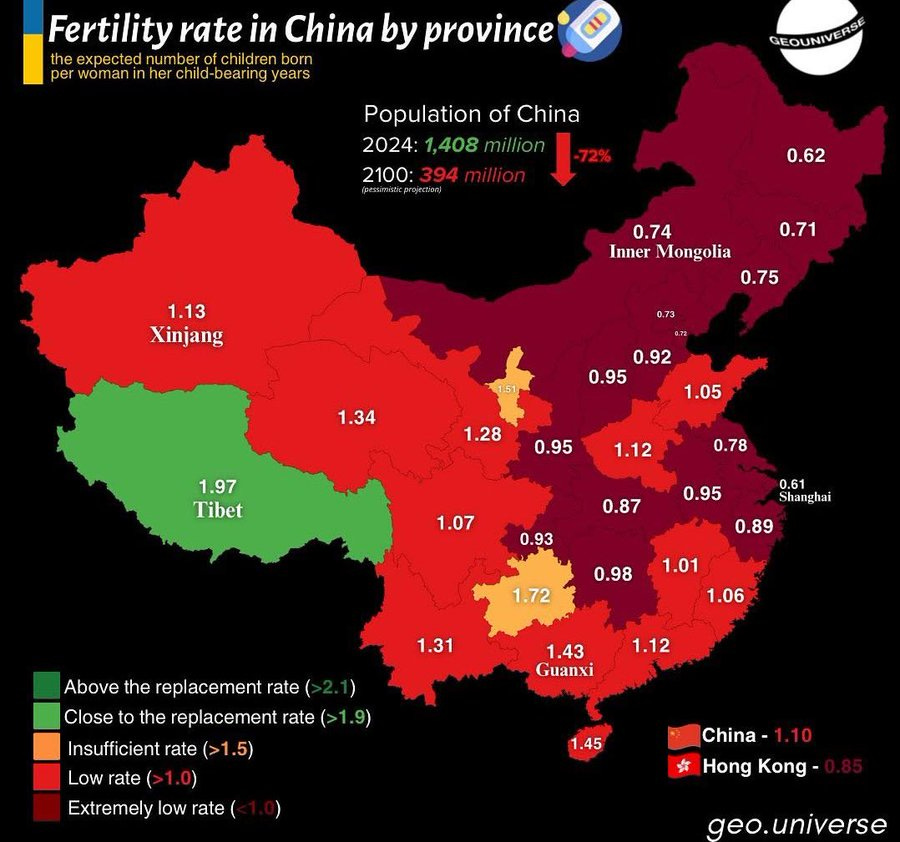

China did have a widespread improvement from 2023 to 2024, but only to 1.1, and this was plausibly because it was the Year of the Dragon. In 2025 things seem back to 2023 levels, so it doesn’t look like they’ve turned a corner.

China’s marriage rate is collapsing, now less than half of its peak in 2013, and down 20% in only one year.

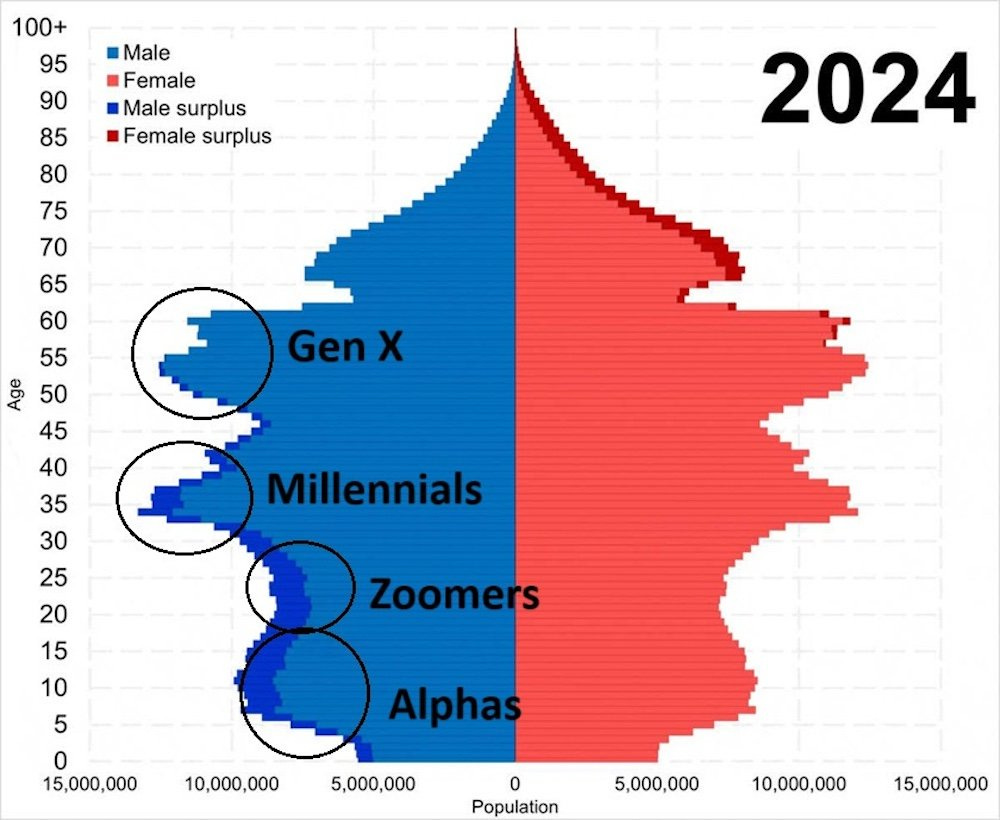

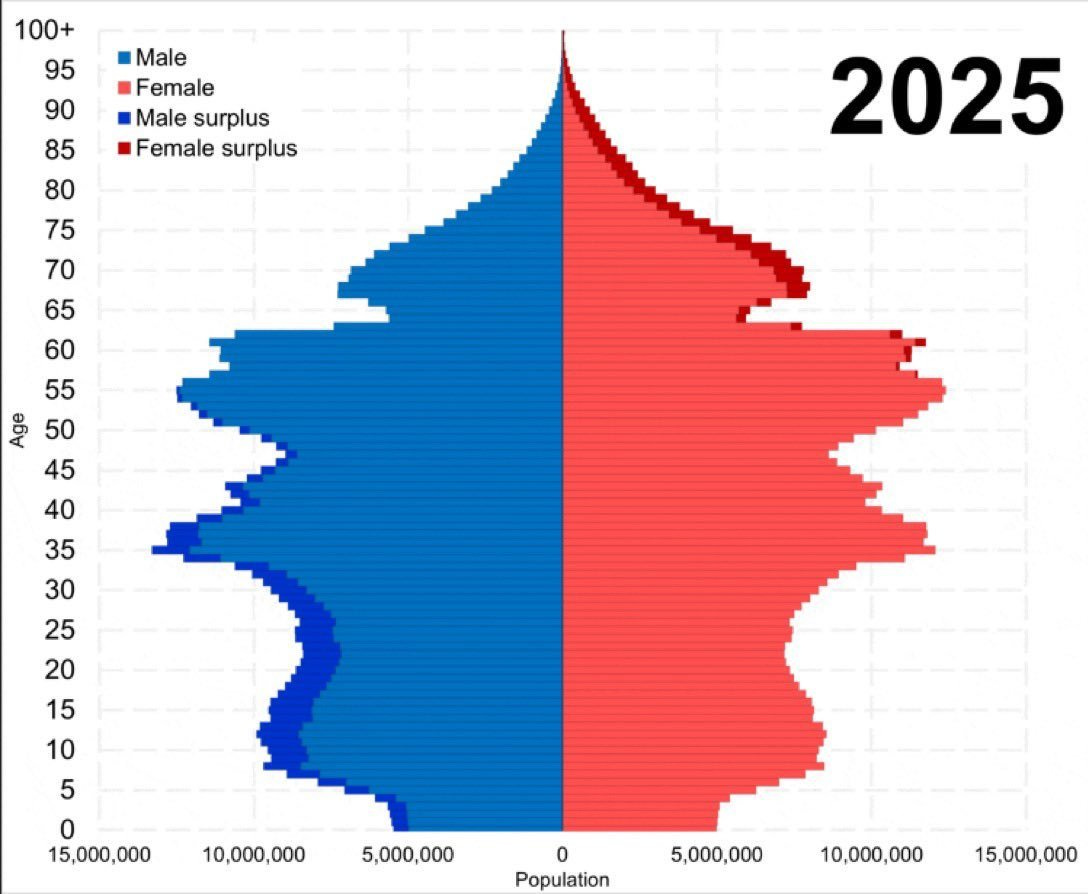

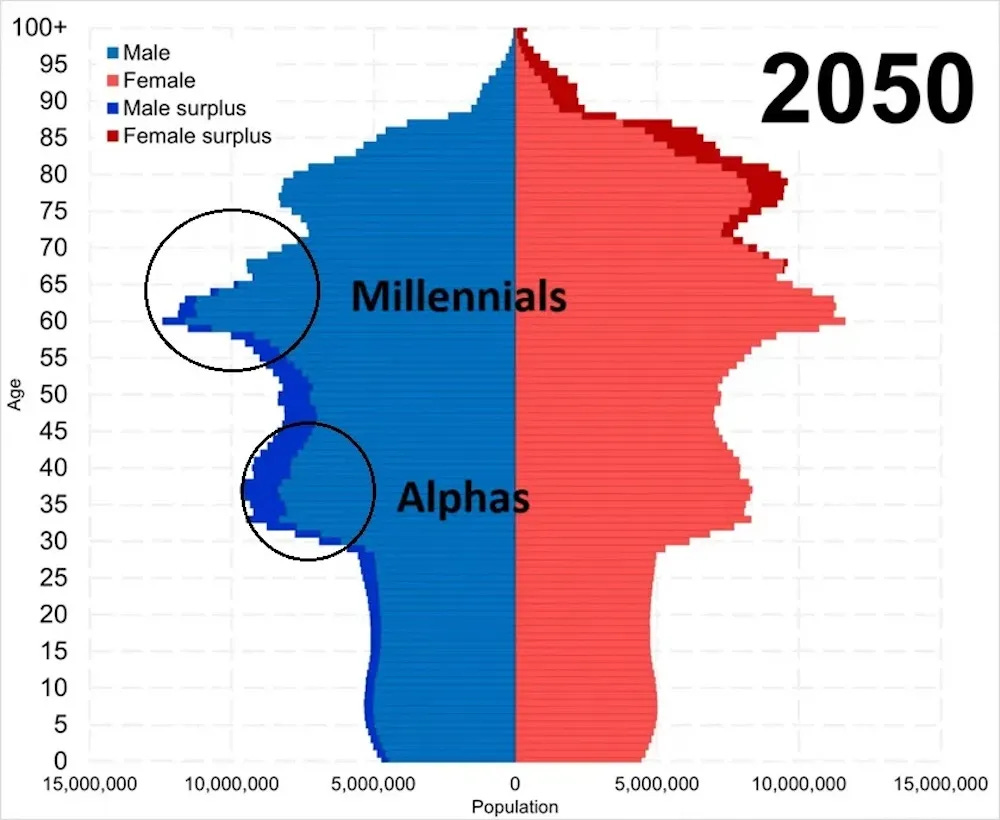

As a reminder, these are the demographics, they do not look good at all, watch the whole chart slowly creep older and the bottom crisis zone that started in 2020 expand.

Jonatan Pallesen: China’s population pyramid is dire.

• The last large cohort of women, those aged 34 to 39, is rapidly moving into the non-reproductive age range.

• There is an extreme surplus of males. More than 30 million. These are men who cannot possibly find a wife, an enormous population of incels by mathematical necessity.

• Since around 2020, the number of children born has completely collapsed and shows no sign of recovery. In a few decades, China will be full of elderly people and short on workers.

Marko Jukic: There is not going to be a Chinese century unless they become the first industrialized country to reverse demographic decline. Seems unlikely, so the default outcome by 2100 is a world poorer than it is today, as we aren’t on track to win the century either.

AI will presumably upend the game board one way or another, but the most absurd part is always the projection that things will stabilize, as in:

The article has that graph be ‘if China’s fertility rate doesn’t bounce back.’ Whereas actually the chart here for 2050 is rather optimistic under ‘economic normal’ conditions.

Their overall map looks like this:

They are at least trying something in the form of… changes to divorce?

One change in particular seems helpful, which is that if a parent gifts the couple real property, it stays with their side of the family in a divorce. I like this change because it makes it much more attractive to give the new couple a place to live, especially one big enough for a family. That’s known to have a big fertility impact.

What impact will that have on fertility?

Samo Burja: China might have just undertaken the most harsh and serious pro-fertility reform in the world.

It won’t be enough.

But this shows they have political will to solve fertility through any means necessary even if it doesn’t look nice to modern sensibilities.

Ben Hoffman: This doesn’t seem well-targeted at fertility. If fertility is referenced it’s a pretext.

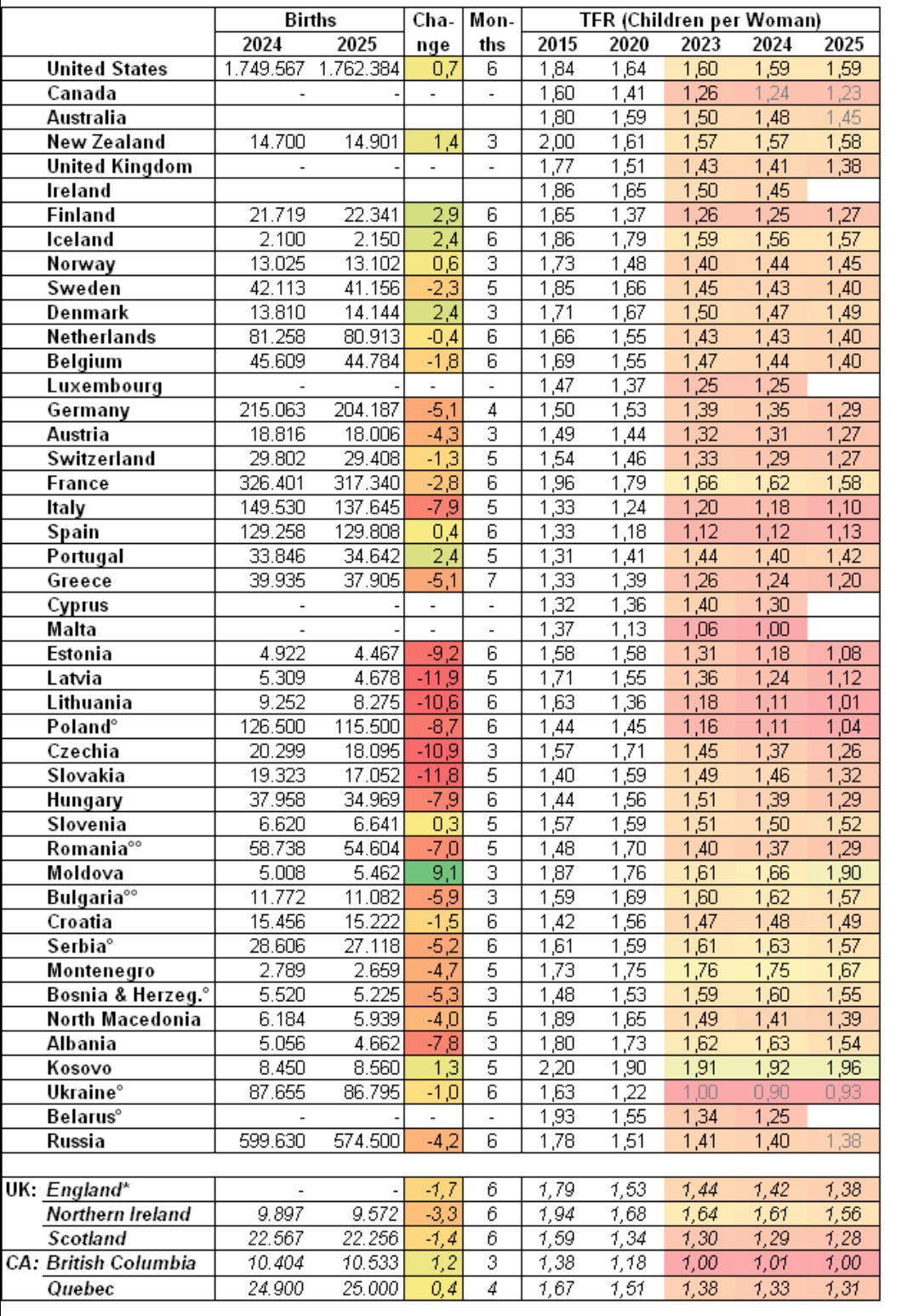

Russia

Russia’s birth rate continues to rapidly drop to its lowest point in 200 years, with its population actively declining. Having started a protracted war is not helping matters.

Europe

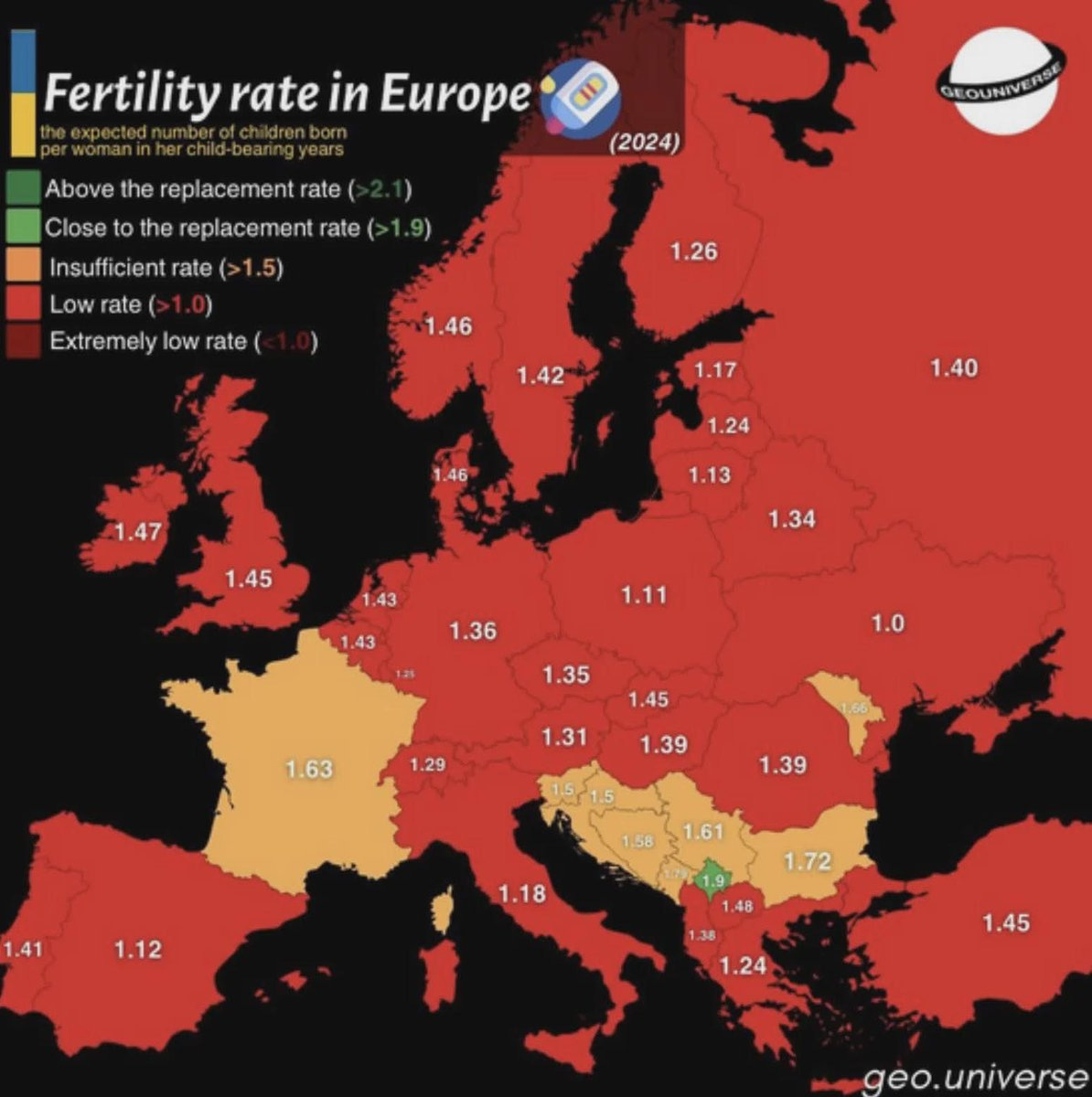

Rothmus: It’s so over.

Dan Elton: Douglas Murray seems right on this point — “Western” culture will survive, but specifically European cultures will not, except for small vestiges maintained for tourists.

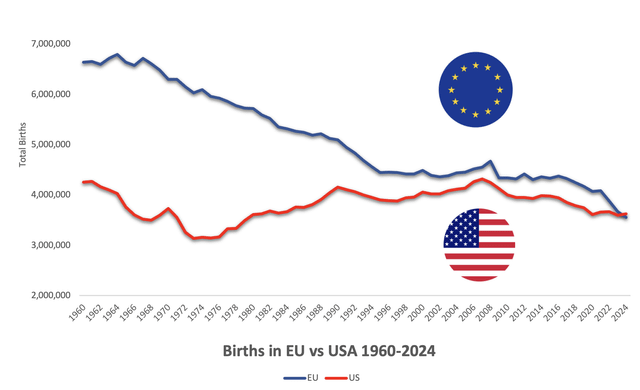

Francois Valentin: For the first time in its history the EU recorded fewer births in 2024 than the US.

Despite having an extra 120 million inhabitants.

America

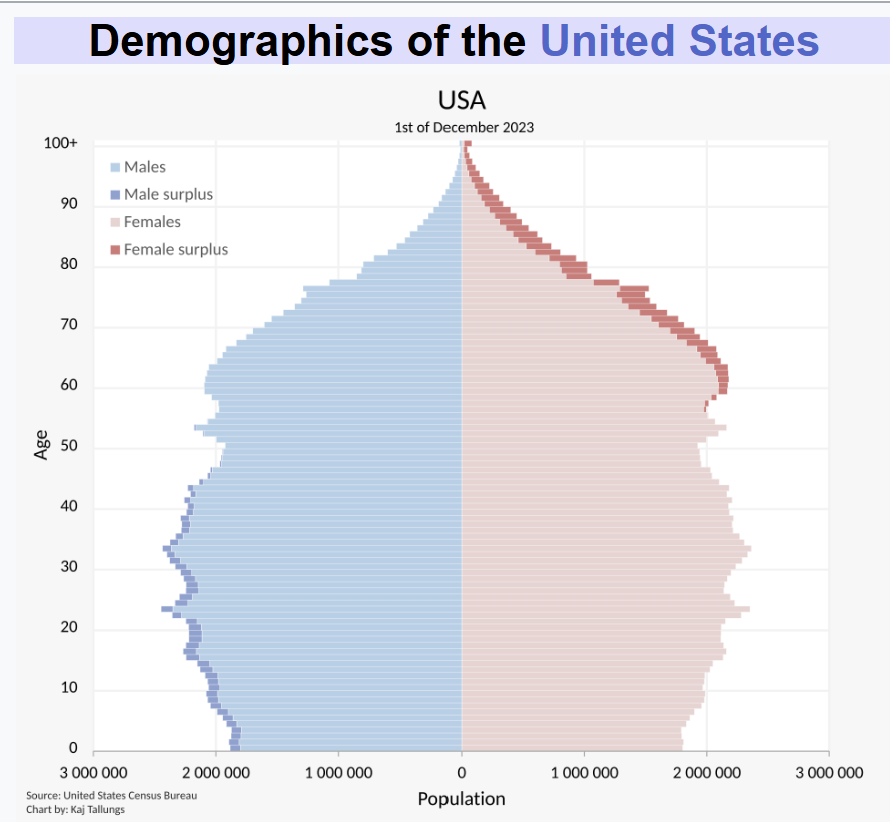

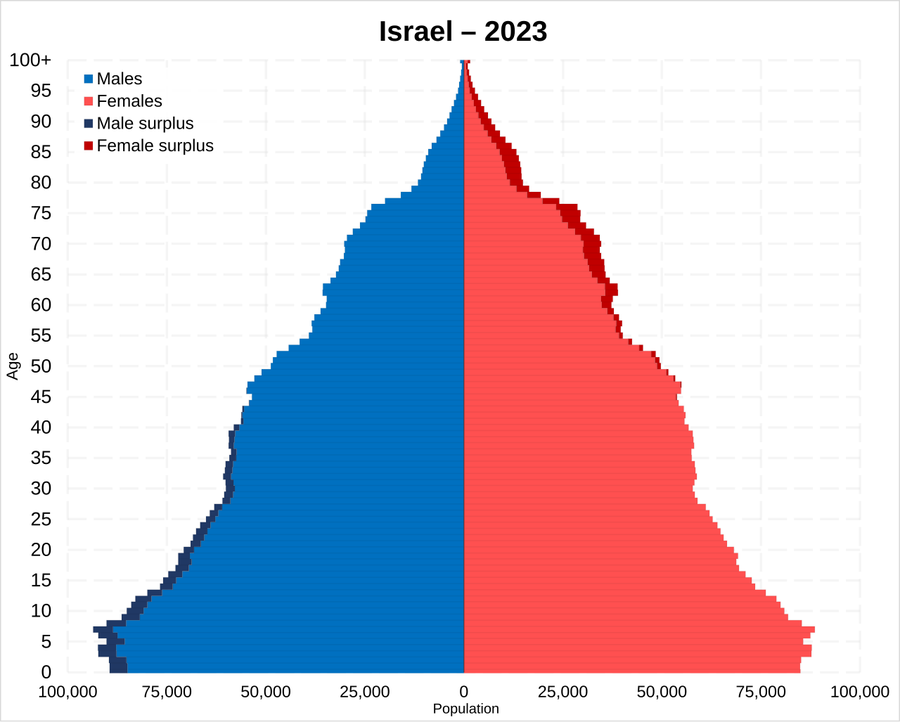

This is what a relatively healthy demographic graph looks like in 2025.

John Arnold: Forget office to resi. We need college campus to retirement community conversions.

We still primarily need office to residential because of the three rules of real estate, which are location, location, location. You can put the retirement communities in rural areas and find places you’re still allowed to build.

New Mexico to offer free child care regardless of income. As usual, I like the subsidy but I hate the economic distortion of paying for daycare without paying for those who hire a nanny or stay home to watch the kids, and it also likely will drive up the real cost of child care. It would be much better to offer this money as an expanded child tax credit and let families decide how to spend that, including the option to only have one income.

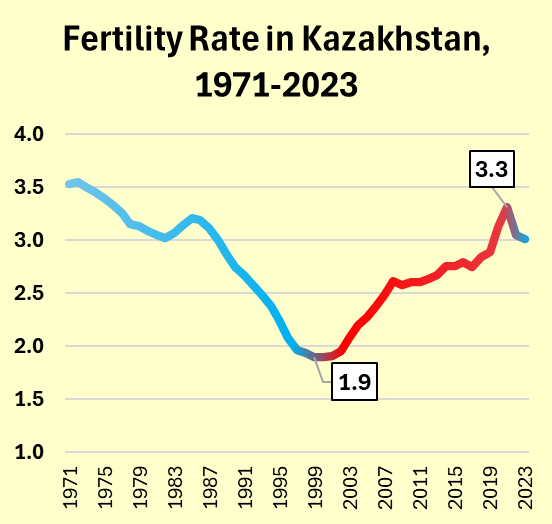

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan remains the existence proof that fertility can recover, with economic recovery and growth boosting seemingly rather than hurting fertility as they recovered from the economic woes they experienced in the 1990s.

Israel

More Births looks into how Israeli fertility remains so high.

More Births: On the combined measures of income and fertility, one nation is far ahead of the rest. Israel’s score laps every other country in this index. High fertility countries usually have very low GDPs and high GDP countries usually have very low birthrates. Israel is the only country in the world that does well in both categories.

Israel has high levels of education. It has high housing costs. It has existential threats from outside, but so do Ukraine and Azerbaijan. Israeli levels of religiosity are unremarkable, only 27% attend a service weekly and secular Jewish fertility is around replacement. Social services are generous but not unusually so.

Ultimately, those who live in Israel or talk to Israelis almost always arrive at the same conclusion. Israeli culture just values having children intensely.

… Another wonderful article, by Danielle Kubes in Canada’s National Post, offers precisely the same explanation for high Israeli fertility: Israel is positively dripping with pronatal belief.

The conclusion is, a lot of things matter, but what matters most is that Israel has strong pronatal beliefs. As in, they rushed dead men from the October 7 attacks to the hospital, so they could do sperm extractions and allow them to have kids despite being dead.

Consequences

Fix your fertility rate, seek abundance beyond measure, or lose your civilization.

Your call.

Samo Burja: As far as I can tell, the most notable political science results of the 21st century is democracy cannot work well with low fertility rates.

All converge on prioritizing retirees over workers and immigrants over citizens escalating social transfers beyond sustainability.

I think this means we should try to understand non-democratic regimes better since they will represent the majority of global political power in the future.

It seems to me that the great graying and mass immigration simply are the end of democracies as we understood them.

Just as failure to manage an economy and international trade were the end of Soviet Communism as we understood it.

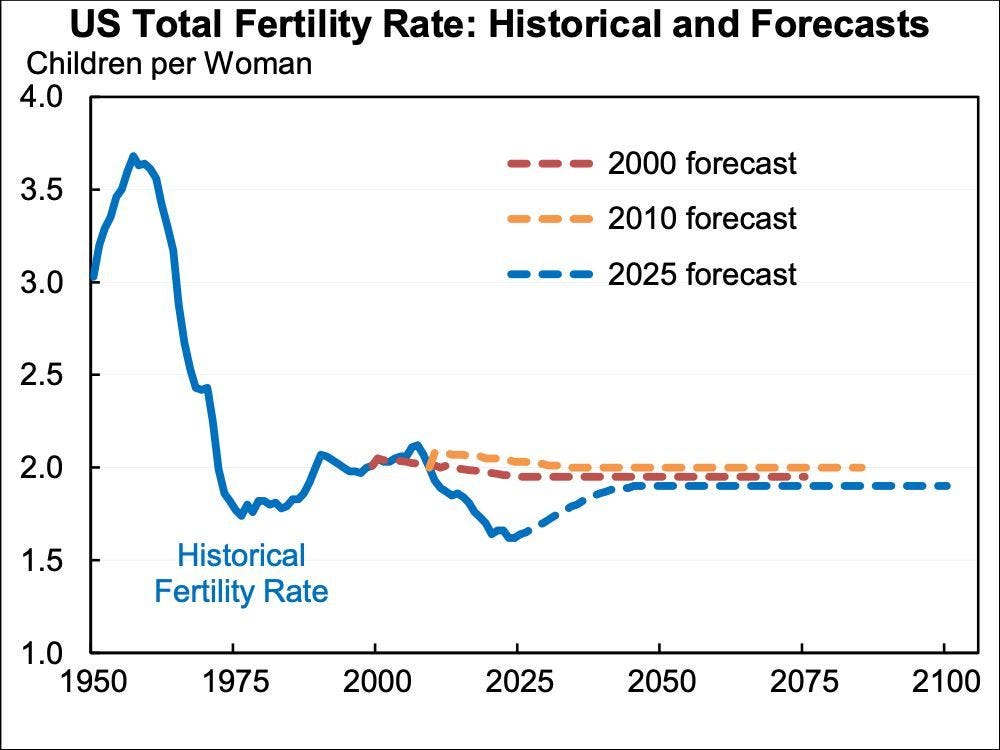

Unfounded Optimism

Why do official baseline scenarios consistently project recovering fertility rates?

Kelsey Piper: always a great sign when a projection is “for completely mysterious reasons this trend will reverse starting immediately and return to the baseline we believed in 25 years ago”

Jason Furman: Fertility rates are way below what the Social Security Trustees projected in both 2000 and 2010. And yet they have barely updated their long-run forecast. What’s the best argument for the plausibility of their forecast?

Compare the lines. This is not how a reasonable person would update based on what has happened since the year 2000. It could go that way if we play our cards right, but it sure as hell is not a baseline scenario and we are not currently playing any cards.

History

Whyvert: Gregory Clark has evidence that Britain’s upper classes had low fertility 1850-1920. This would have reversed the earlier “survival of the richest” dynamic. It may partly explain Britain’s relative decline from the late 19th century.

For most of history the rich had more children that survived to adulthood than the poor. Then that reversed, and this is aying that in Britain this happened big time in the late 1800s.

Claim that only 1% or less of children are genetically unrelated to their presumed fathers, very different from the opt-repeated figure of 10%. That’s a very different number, especially since a large fraction of the 1% are fully aware of the situation.

Implications

The Social Security administration and UN continue to predict mysterious recoveries in birth rates, resulting in projections that make no sense. There is no reason to assume a recovery, and you definitely shouldn’t be counting on one.

I do think such projections are ‘likely to work out’ in terms of the fiscal implications due to AI, or be rendered irrelevant by it in various ways, but that is a coincidence.

Fertility going forward (in ‘economic normal’ worlds not transformed by AI) will have highly minimal impact on climate change, due to the timing involved, with less than a tenth of a degree difference by 2200 between very different scenarios, and it is highly plausible that the drop in innovation flips the sign of the impact. It is a silly thing to project but it is important to diffuse incorrect arguments.

The motherhood penalty thing...even outside of greedy careers (the salary structure for bagging groceries is pretty flat, obviously), even with pronatalist inclinations, I find myself sympathetic to the business side. We've had one manager out for over a year(!) on maternity leave at this point, with that position held open all this time at same compensation, hours, etc. Doesn't matter so much when we're at full managerial capacity, others can step up to fill the void. When we're down some though...and can't easily acquire more managers, because "on paper" she still counts as filling a spot, and it'd be awkward to only temporarily promote someone...it's just a headache. Like obviously the solution isn't to force her to come back to work, or demotion, or whatever. But children are a public good, and so having a private company subsidize this ongoing expense-in-absentia simply rankles. That's poor systems design, especially when a company does try hard for parity in hiring and promotion...shouldn't punish for doing the right thing.

Re Israel, the underrated second factor is Israelis' willingness to just start doing things and trust in figuring them out as we go along. It's the opposite of Korean culture in that way, and it's also the reason Israel has great startups and lousy infrastructure.