It’s time for another housing roundup, so I can have a place to address the recent discussions about the local impact of housing construction on housing costs.

Does Increasing Local Housing Supply Decrease Local Housing Prices?

Scott Alexander says Change My Mind: Density Increases Local But Decreases Global Prices. He uses this graph to make his point:

Under this theory, YIMBY is still correct general policy as it lowers prices everywhere else, yet locally increasing supply improves quality of life and thus induces even more demand and raises prices.

Scott Sumner explains why I strongly believe Scott Alexander is wrong here.

Here’s the core point:

Scott Sumner: [Scott Alexander] is aware that the pattern above may show an upward sloping supply curve, not an upward sloping demand curve. But he nonetheless suggests that it’s probably an upward sloping demand curve, and that building more housing in Oakland would make Oakland so much more desirable that prices actually rise, despite the greater supply of housing. I have two problems with this sort of argument.

First, I doubt that it’s true. It is certainly the case that building more housing can make a city more desirable, and that this effect could be so strong that it overwhelms the price depressing impact of a greater quantity supplied. But studies suggest that this is not generally the case.

Texas provides a nice case study. Among Texas’s big metro areas, Austin has the tightest restrictions on building and Houston is the most willing to allow dense infill development. Even though Houston is the larger city, house prices are far higher in Austin.

This is basic common sense.

Places that impose severe NIMBY restrictions get very high prices.

All the most expensive places in America impose such restrictions, and make it impossible to build more housing.

The places that don’t impose such restrictions have lower housing prices than their populations would otherwise suggest.

This theory implies existing homeowners benefit from new construction, as it raises their property values, so they both gain utility and gain resale value. Yet they reliably oppose such construction.

It’s not impossible for all that to be compatible with a tiny increase in housing supply increasing prices due to the fantastic increased value provided by network effects. It is still profoundly weird.

If this is all true it is an overwhelming case to build more housing.

We can decompose the value of an apartment, for sale or rent, into two components.

The value provided by this housing.

The scarcity of similar housing.

If house or rent prices go up due to more value being provided, that’s good.

If house or rent prices go up due to more scarcity, that’s bad, value is lost.

Sumner generalizes my thinking and points out how awesome building more housing would be if it raised local housing prices:

Scott Sumner: Of course, economic change always has winners and losers. Here’s how I would describe the impact of allowing more housing construction in Oakland, in the unlikely event that this did raise housing prices:

1. America would benefit.

2. Oakland would benefit.

3. Poor people in America would benefit, in aggregate.

4. Affluent people in America would benefit, in aggregate.

5. Homeowners in Oakland would benefit.

6. Some renters in Oakland would benefit (from a more economically dynamic city.)

7. Some renters in Oakland would suffer from higher rents.

In the much more likely case where new housing construction would lower prices, the impact described in #5 and #7 might reverse. Either way, there is no defensible argument for not building more housing in Oakland, regardless of the impact on price. If building more housing reduces its price, then there is a strong argument for allowing more housing construction. If building more housing raises its price, then the argument for more construction is even stronger.

Emmett Shear (cofounder of Twitch) explains his model in this Twitter thread.

In Shear’s model, high density living is undersupplied and highly desirable. NYC and SF are expensive because they are so dense. When density increases, prices go up. However, people move and adjust slowly, so it takes a while for prices in an area to appreciate the value of this new density. That means that adding more housing temporarily suppresses prices via ordinary supply and demand, until demand adjusts upwards, which at equilibrium means higher prices.

This model would be true if people choosing where to live mostly care about density per se density. Places are mostly valuable because they are dense, this model says, rather than places being dense because they are valuable.

I think this is wrong. San Francisco and New York are valued for their density and the results of being dense, but also highly valued for other reasons. If Las Vegas built itself up to be as dense as Manhattan, even if all that housing was occupied and then it stopped building, it would not get Manhattan prices.

Notice his final note.

Emmett Shear: There are only two proven ways out of this situation, if you want to reduce the price of housing in your city. The first is the way of Vegas: Just Keep Building. The second is the way of Detroit: if you get rid of enough jobs, people will have to leave.

San Francisco is trying a novel approach, where we try to destroy the quality of life in the city while keeping everyone grinding at their jobs. So far so good on destroying quality of life, but empirically prices just aren’t going down.

I think SF is just too fundamentally beautiful for this approach to work, tbh. And the economic powerhouse that is infotech doesn't seem to be slowing down.

There is nothing intrinsically expensive about high density regions, or low density regions. We just chronically underbuild high density by making it illegal to construct more. Until we construct a huge amount more housing in our biggest metro areas, prices will remain high.

The same thing happens in very desirable low density regions when supply is constrained. You get sky high prices in Aspen, CO too, which is incredibly expensive vs its density. It's just we write those off as enclaves for the rich, instead of cities everyone needs to live in.

This contradicts the model where value is primarily density. San Francisco has huge advantages that it is trying desperately to squander, that make it far more valuable than its density implies. Aspen is the same except with less squandering.

In the sufficiently long run, would San Francisco housing be more or less expensive with more housing and more residents, if it then stopped building once again? I don’t know. I can see that going either way.

I also don’t think that is anything anyone should worry about. As with Scott Sumner’s model, Emmett Shear’s model is screaming at you to Build More Dense Housing. If anything it is screaming even louder. The ‘bad scenario’ is that in the future, we might have more people paying more money for something that got a lot more valuable, each capturing more surplus, while owners of land and housing get richer. Or we could go with the ‘Vegas solution’ and keep building more housing.

Peter Thiel Asserts That Moving Sucks

Peter Thiel has a strange housing costs take (Bloomberg).

Billionaire tech investor Peter Thiel said he’s reluctant to move his operations to Florida from Silicon Valley because housing prices have soared.

Peter Thiel: If you buy a house in Miami today versus just three years ago, you’re paying four times as much for a monthly mortgage payment,” Thiel said on the podcast Honestly with Bari Weiss.

…

That kind of economic cost is probably not enough to offset all the wokeness in the world or even the taxes.

Bing, you’re up.

Bing: According to my sources, the average home prices in Miami, Los Angeles and San Francisco vary. The median sale price of a home in Miami was $560K last month. The median sale price of a home in Los Angeles was $980K last month. The median sale price of a home in San Francisco was $1.4M last month. According to my sources, the average home prices in Silicon Valley are around $1.25 million.

According to my sources, in May 2020, the median sales price of a single-family home in Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach MSA (Broward, Miami-Dade, and Palm Beach counties) increased by 2.1% to $372,5001.

I notice that $560k is rather a lot less than $1.25 million. $560k is 50% more than $372k, but I don’t see how that matters. The real change is that the average mortgage rate has gone (for a 30-year fixed) from 2.96% to 6.79%.

This matters if and only if one is forced to give up a 3% mortgage for a 6.8% mortgage. You’ll pay 6.8% everywhere, and in Miami on half the amount. So yes, this move would be expensive to people who are sitting on valuable low-interest mortgages, and who would be forced to sell without realizing those gains, I suppose?

In exchange, you get forward-looking housing costs down by half and get away from 10% marginal tax rates. No matter how you value getting away from wokeness, as long as that amount isn’t highly negative, I notice I am confused.

The only way this makes sense is if the real claim is that no one with a mortgage can afford to move, at all, including across the street, due to lock-in. There’s some truth in that. It would be good if you could settle with your bank to lock in your profits, but in practice you can’t.

Political Developments

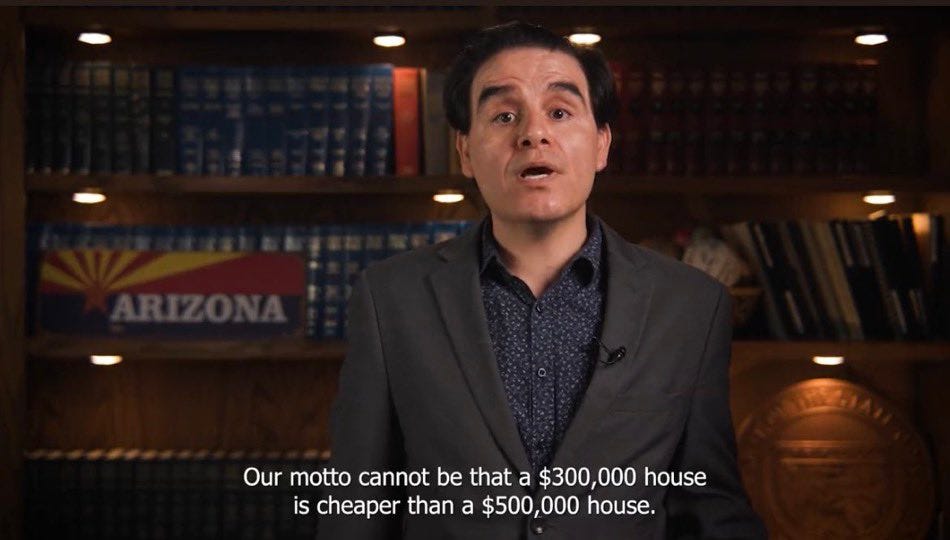

Arizona State Democrats play a clip ‘explaining the shortcomings of #SB1117.’ All faces involved remain straight, and no this is not being taken out of context.

Washington State senate votes 49-0 to exempt housing projects from environmental review. And more. This is The Way:

The concern on the WA bill is that it only requires state council to adopt code by 2026, then it’s up to the cities, although most cities do whatever is suggested to them according to Dan Bertolet. I never fully understand why the delays and half-measures are helpful. Do they help much with winning votes? I’d have thought no.

California Builder’s Remedy prediction market watch.

San Francisco disallows large windows because they ‘were a statement of class and privilege.’ Direct kindergarten-level justification for outright sabotage. You did not bring enough large windows for the whole class, so no one gets a large window.

San Francisco also gives $1mm/year in housing funds to TODCO, an ‘affordable housing nonprofit’ that extensively lobbies against the construction of housing and also seems to not care to maintain its subsidized apartment buildings given it is under no financial pressure to do so, similar to slumlords under rent control.

You say you want to build 100% affordable housing in San Francisco? Until April 19, at least, the correct response was good luck with that. 87 permits, 1,000 days of meetings and $500,000 in fees: How bureaucracy fuels S.F.’s housing crisis.

Then, something very interesting happened. London Breed, mayor of San Francisco, issued an array of new housing rules.

Fry: First off, (1) it removes most Conditional Use and mandatory public hearing requirements. You might be wondering: what is Conditional Use? So... SF has long had a *legal requirement* that many types of housing go through dramatic, drawn-out, nonsensical public hearings.

Mayor Breed's legislation abolishes Conditional Use and mandatory public hearings for most types of housing and new construction. (!!!!!!)

Next up, (2) this legislation also cuts up to $100,000-$150,000 in fees that San Francisco has historically charged to each new unit of affordable housing.

The third and final bucket of reform: (3) Undo bizarre restrictions in our Planning Code that don't make sense for a fair, dense, multiuse, and vibrant city.

In addition to waiving conditional uses, this legislation also erases geographic requirements that say you can't have new senior housing, homeless shelters, group housing, or home-based businesses in all San Francisco neighborhoods.

And it also eases rigid, inflexible requirements for balconies, inner courtyards, and ground floor apartment uses like shared laundry, mail rooms, bike rooms, and lobbies.

Why does this matter? Much of city planning and architecture is actually about problem solving through a maze of strict, confusing, and often conflicting rules. The design you get at the end represents the delicate (and strange) path that complied with all the rules.

Last one.

Under current SF law (a rule that has been in place for the entirety of our housing shortage spiral, unsurprisingly)... To get a permit to build or renovate, you have to send a letter to all neighbors who live within 150ft asking for permission.

Neighbors, in return, can say "no actually I don't like it" once they get the letter. After all, you had to ask for permission! And then they can stop the project until they get their way in a public hearing at City Hall.

This is obscene. Mayor Breed is getting rid of it.

This is The Way. Those are certainly far from all of San Francisco’s barriers to building housing. They are still a giant set of leaps forward towards the ability to build housing.

I don’t have a good sense of what percentage of the barriers this constitutes, or how much it helps to get rid of some but far from all of the veto points. My guess is this will be a real yet modest gain.

California chose to budget $300 million dollars to subsidize demand via the strategy ‘pay for first time home buyers down payments.’ Hope you got in on all this free money they were handing out, sorry if instead you’re paying taxes to fund it. This lasted for two weeks and went to 2,300 people. And bonus, ‘first time home buyer’ includes (as is the federal standard) anyone who hasn’t owned a house in the past three years, even if they previously owned a house, because words have no meaning.

The correct California strategy is therefore presumably either to lock in immunity to taxation via not moving for decades, or if it’s too late for that to not buy (and sell if you already own) until you can get a giant gift attached.

Washington D.C. mayor offers big tax breaks for those who convert offices to housing. As usual, the better ‘subsidy’ would be to get rid of all the regulations and laws preventing or limiting such conversions, if they could rent the office space to people as apartments without worrying about things like window requirements I bet that would be a lot better at inducing conversions while not costing any money.

New York City Housing is Expensive

New York City housing is setting records again.

Mayor Eric Adams is also at least talking the talk.

Governor Kathy Hochul is going YIMBY. People don’t always take kindly.

So of course the NY Assembly GOP says:

NY's "housing crisis" has ZERO to do with available units. Look around; plenty is vacant.

Real housing crisis has EVERYTHING to do with NYers not being able to afford what they currently own/rent because Democrats have been taxing us to death for decades.

Taxes keeping apartments vacant does not make any sense unless the tax is on rent, which it isn’t. The term they are looking for here is ‘rent control.’

Not that getting rid of that would mean we had enough housing. It would help.

The latest goodbye to SF in favor of NYC still cites ‘much lower cost of living’ as one reason for the move.

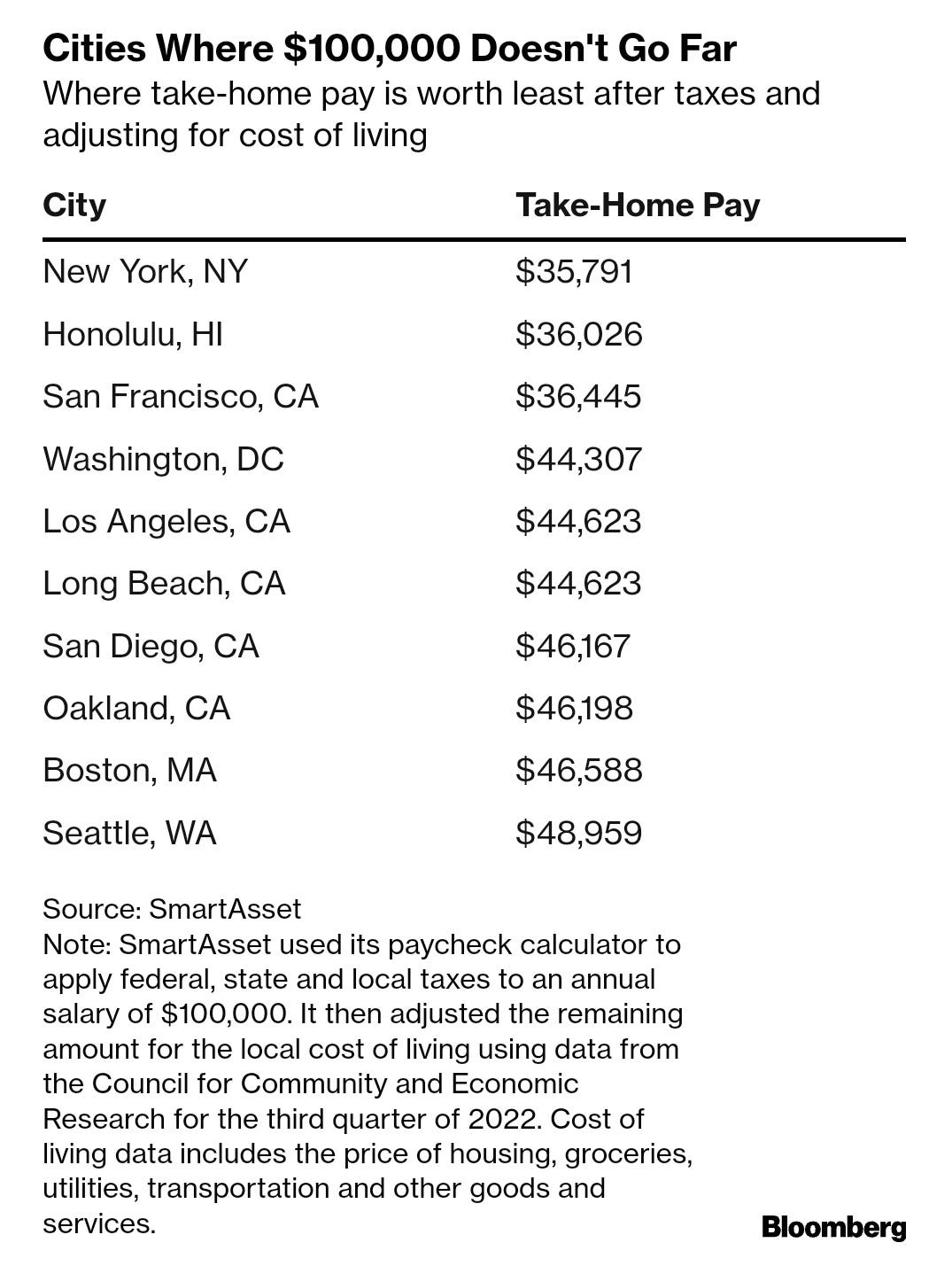

This study finds that take-home pay in NYC on a $100k salary, after adjusting for taxes and living costs is ‘effectively’ only $36k, if you don’t take into account that a lot of what you are buying is ‘you get to live in NYC’ hence the higher prices. Really weird scale, since you then get to spend that $36k as if you were paying Memphis prices, or something? I’ll happily take that deal.

In Other Housing News

Matt Yglesias makes the case against preserving old buildings that are not providing any value to anyone, pointing out that the main use of such preservation is to intentionally sabotage development. If something historic happened, use plaques and signs to explain it, those are cheap, whereas old non-functional or inefficient buildings take up valuable land and thus are super expensive to keep around, while they provide approximately no tourist or other historic value. Yes, obviously.

Tyler Cowen labeled this correctly as ‘the NIMBY culture that is Britain.’

Construction Physics looks at rising construction costs through the lens of single family homes, concludes that increased regulatory burdens and veto points are not the main driver of our terrible productivity in physically building homes. Yes, we throw up a lot of barriers that drive up costs, but once we start building we still don’t do that any more efficiently than decades ago either, and the rules changes don’t seem unusually burdensome or large there.

I believe this analysis misses that we are doing things the same way we did them decades ago because of these restrictions, we are not allowed to innovate and do better things, and also I am guessing it misses a lot of ‘passed through’ other regulatory problems. Essentially, if everything you do in construction is subject to multiple veto points, it becomes impossible to iterate, innovate and improve, you can only keep doing the same things over and over again, because the risks of doing otherwise are too high. So nothing ever changes. Which means nothing ever changes.

Transit

Transition from yellow cabs to Uber as the world centralizing, allowing power to prevent you from riding taxis, whereas yellow cabs paid with cash are impossible to shut off. He doesn’t mention that it also gives power ability to track your movements. As he notes, at least for now this definitely makes everyone better off due to things working better, but long term power will compromise them more and more, and use them as leverage. I am not as worried about it as he is, but I agree we should definitely be worried.

Then, of course, he proposes his solution, which if you saw his Twitter icon and name you very much saw coming, ‘crypto and NFTs.’ And, well, no. In practice none of this will help. You can have all the crypto you want, it will not hail you an Uber or Lyft, and if power decides you don’t get one then you are not going to create a rival crypto-based decentralized taxi service power can’t touch, and if you did it would be illegal, and if they let you keep it then few would use it because it would be a worse experience and you would fail at economies of scale. Sorry, man.

"I think this is wrong. San Francisco and New York are valued for their density and the results of being dense, but also highly valued for other reasons."

Are they though? It seems like basically everything that would suggest that the notion that living in NYC or SF is desirable is, to first order (or *at most* second order) the result of agglomeration effects. The putative amenities aren't really taken advantage of on anything like the scale of day to day living (as the Onion observes "nobody goes to the Met anyway," - and if you did, it would be weird to pay rent through the nose 364 days a year to save a trip of a couple of hours to NYC on the 365th). And heaven knows it isn't the schools. Basically every reason to actually *live* in New York or similar urban metropolises at eyewatering rents with low per-person space and lousy public schools seems to round out to "the labor market is robust and pay is higher" - which I think can comfortably be called an agglomeration effect. Everything else seems more like a reason at most to visit rather than a reason to forgo more space at lower cost at all times.

[ Onion article referenced above: https://www.theonion.com/8-4-million-new-yorkers-suddenly-realize-new-york-city-1819571723 ]

Years ago I was thinking of moving in to downtown Seattle from the suburbs to eliminate my commute. I was shocked to find that pretty much every high rise had absurd HOA fees, and a quick search through listings on Zillow confirms this is still true. Here's an 800 sq ft unit for $600,000 but with a $910 per month HOA fee: https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/909-5th-Ave-UNIT-1805-Seattle-WA-98164/83230588_zpid/

At the time I had assumed that there was something about high-rises that was just far more expensive to maintain. Maybe it's the elevators, or seismic compliance, the plumbing, something else? But the maintenance cost for that 800 sq ft condo is far higher than would be the maintenance cost on an 800 sq ft bungalow, even factoring in that every 20-30 years you'd need to pay for your own new roof.

Suppose that density doesn't actually increase local *prices*, might it still not increase local costs?