Medical Roundup #6

The main thing to know this time around is that the whole crazy ‘what is causing the rise in autism?’ debacle is over actual nothing. There is no rise in autism. There is only a rise in the diagnosis of autism.

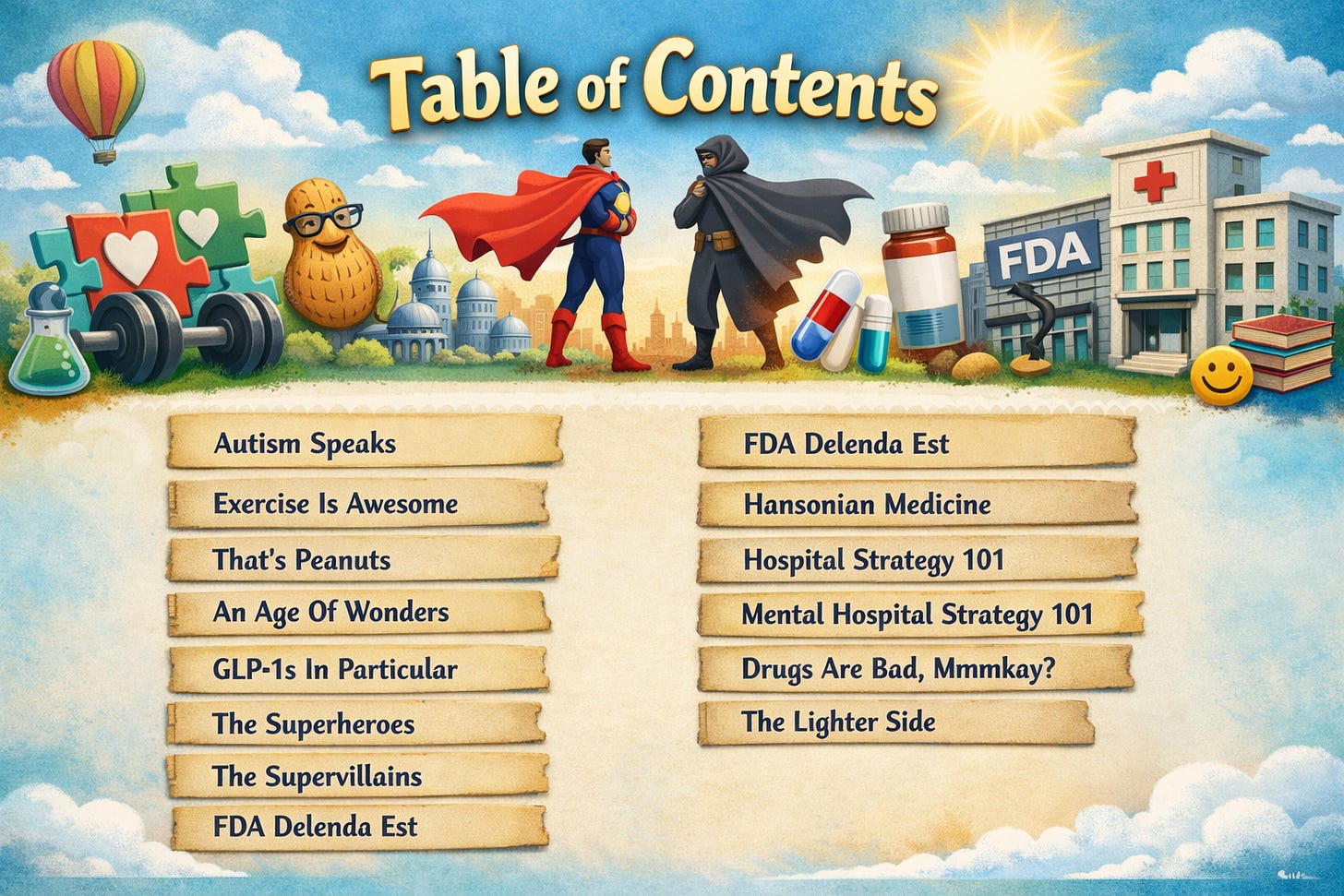

Table of Contents

Autism Speaks

It has not, however, risen in prevalence.

The entire shift in the rate of diagnosis of autism is explained by expanding the criteria and diagnosing it more often. Nothing actually changed.

We already knew that vaccines don’t cause autism, and that Tylenol doesn’t cause autism, but now we know such things on an entirely different level.

I admit that this result confirms all of my priors and thus I might be insufficiently skeptical of it, but there are a lot of people with what we in 2026 call autism that are out there, they love picking apart such findings, and I’ve seen zero of them question the statistical result.

Autism used to mean something severe enough to render a child non-functional.

It now means someone capable of thinking clearly who insists words have meaning.

It also still means the first thing, and everything in between.

Using the same word for all these things, and calling it the autism spectrum, does not, overall, do those on either end of that spectrum any favors.

Matthew Yglesias: Study confirms that neither Tylenol nor vaccines is responsible for the rise in autism BECAUSE THERE IS NO RISE IN AUTISM TO EXPLAIN just a change in diagnostic standards.

The D.S.M.-III called for a diagnosis of infantile autism if all six of these criteria were met:

Onset before 30 months of age

Pervasive lack of responsiveness to other people

Gross deficits in language development

Peculiar speech patterns (if speech is present) such as immediate and delayed echolalia, metaphorical language, or pronominal reversal

Bizarre responses to various aspects of the environment, e.g., resistance to change, peculiar interest in or attachments to animate or inanimate objects

Absence of delusions, hallucinations, loosening of associations, and incoherence, as in schizophrenia

This is clearly describing a uniformly debilitating condition, especially in terms of criteria (3) and (4).

That is very, very obviously not what anyone centrally means by ‘autism’ in 2025, and we are going searching for it under every corner.

By the time the D.S.M.-IV came out in 1994, things like “lack of social or emotional reciprocity” when combined with “lack of varied spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level” could qualify a child for an autism diagnosis, as long as they also have trouble making eye contact.

Cremieux: The result is consistent with 98.25% of the rise being due to diagnostic drift and that’s not significantly different from 100%.

Bryan Caplan: Occam’s Razor. No one in my K-12 was called “autistic,” but there were plenty of weird kids.

Should the Autism Spectrum therefore be split apart? Yes. Obviously yes.

Derek Thompson: I think the answer to this question is clearly yes.

The expansion of the autism diagnosis in the last few decades has created a mess of meaning. It’s not helpful that “autism spectrum” now contains such an enormous bucket of symptoms that it applies to non-verbal adults requiring round-the-clock care and ... Elon Musk.

The expansion of the autism spectrum label is especially poor for those at either extreme. It destroys clarity. It causes large underreactions in severe cases. It causes large overreactions in mild cases, including treating such children in well-intended but highly unproductive ways.

It also is, as Michael Vassar points out, effectively part of a war against caring about truth and whether words have meaning, as anyone who does so care is now labeled as having a disorder. To be ‘normal’ rather than ‘neurodivergent’ you have to essentially show you care deeply about and handle social dynamics and trivialities without having to work at this, and that you don’t care about accuracy, whether words have meaning or whether maps match their territories.

Exercise Is Awesome

Seriously, one cannot write ‘most people need to exercise more’ often enough.

I heard a discussion on NPR’s Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me where a study uncovered that as little as half an hour a week of light exercise can do a substantial amount of good. The response from everyone was to joke that this means they didn’t need to do any more than that and doing anything at all made them heroes. And yes, there’s big gains for ‘do anything at all’ rather than nothing, but there’s quite a lot left to gain.

University students given free gym memberships exercised more and has a significant improvement in academic performance, dropping out of classes less and failing exams less, completing 0.15 SDs more courses. There’s a perversity to hearing ‘this made kids healthy, which is good because they got higher grades’ but if that’s what it takes, okay, sure. The cost-benefit here purely in increased earnings seems good enough.

A large majority of students do not report having financial or time constraints at baseline, which suggests that the free gym card primarily removed psychological barriers to exercise. This is in line with the fact that many participants reported at baseline that they did not exercise at the gym because they were lazy, which may be interpreted as a sign of procrastination.

This all came from an average of 5.7 additional gym visits per student, which isn’t that great a return on a gym membership at first glance. For the effect to be this big there have to be shifts beyond the exercise, something psychological or at least logistical.

There still are very clear diminishing marginal returns.

Thus here is your periodic fitness reminder that although exercising and being in shape is great but there are rapidly decreasing practical returns once you become an outlier in strength, and going deep into gym culture and ‘looking jacked’ has actively negative marginal returns, including in terms of attractiveness and also the injury risk rises a lot.

That’s Peanuts

Exposure to potential allergens as infants decreases allergies, with peanuts being the central example. Carefully avoiding them, as we were for a while told by doctors to do, is exactly wrong. It’s so crazy that our ‘experts’ could get this so exactly backwards for so long, luckily such allergies are on the decline again now that we realize. But as Robin Hanson says, who is there to sue over this epic failure?

An Age Of Wonders

Gene Smith reports that some IVF doctors have figured out how to get much more reliable embryo transfer than the traditional 70%, and also higher egg yields per round. A highly competent IVF practice and doctor can make a big difference, and for now its value could be bigger than those from finding superior embryo selection.

Study finds mRNA Covid-19 vaccines prolonged life of cancer patients, which they claim is via trained immunity from a Type I Interferon surge and activation of MDA5, but it seems they didn’t do a great job controlling for the obvious factor of whether this came from its protective effects against Covid-19? That seems like a giant hole in the study, but they are in Phase III which will settle it either way. If the effect is real you can likely enhance it quite a lot with a combination of mRNA composition and timing the shot to the start of using checkpoint inhibitors.

GLP-1s In Particular

The latest experimental GLP-1 entry from Eli Lilly, is showing the largest weight loss results we’ve seen so far, including big impacts on arthritis and knee pain.

Costco to sell Ozempic and Wegovy at large discount for people without insurance, at $499 a month, the same as Novo Nordisk’s direct-to-consumer website. You do still need a prescription.

Eli Lilly seems to have made a once-daily weight loss pill that works 80%-90% as well as injected Ozempic, with fewer side effects. It’s plausible this would make adaptation much more common, and definitely would if combined with affordable prices and easy access.

Unfortunately an early study suggests that GLP-1s do not, so far, reduce medical spending, with little offset in other spending being observed or projected. Given this is a highly effective treatment that reduces diabetes and cardiovascular risks, that is a weird result, and suggests something is broken in the medical system.

The Superheroes

Elasticity of the supply of pharmaceutical development of new drugs is high. If you double the exclusivity period you get (in the linked job market paper) 47% more patent filings. We should absolutely be willing to grant more profitability or outright payments for such progress.

Australia offers a strong pitch as a location for clinical trials, and as a blueprint for reform here in America if we want to do something modest.

Dr. Shelby: when people talk about Australia for clinical trials, most discourse is round the 40%+ rebates.

BUT, what I haven’t heard discussed is that they don’t require IND packages in some cases. (eg. new insulin format, or new EPO analogues for anemia).

drugs going through this path only need CMC and and ethics approval.

Ruxandra Teslo: Also no full GMP for Phase I. Imo US should just literally copy the Phase I playbook from Australia.

One of the most frustrating experiences in trying to propose ideas on how to make clinical development faster/cheaper, is that ppl who have on-the-ground experience are reluctant to share it, for fear of retribution. The cancel culture nobody talks about.

The Supervillains

Your periodic reminder that today’s shortage of doctors is a policy choice intentionally engineered by the American Medical Association.

Ruxandra Teslo offers another round of pointing out that if we had less barriers to testing potential new treatments we’d get a lot more treatments, but that no one in the industry has the courage to talk about how bad things are or suggest fixes because you would get accused of the associated downside risks, even though the benefits outweigh the risks by orders of magnitude. Ruxandra notes that we have a desperate shortage of ‘Hobbit courage,’ or the type of intellectual courage where you speak up even though you yourself have little to gain. This is true in many contexts of course.

Patrick McKenzie (about Ruxandra’s article): A good argument about non-political professional courage, which is *also* an argument why those of us who have even moderate influence or position can give early career professionals an immense boost at almost trivial cost, by advancing them a tiny portion of their future self.

This is one reason this sometimes Internet weirdo keeps his inbox open to anyone and why he routinely speaks to Internet weirdos. I’m not too useful on biotech but know a thing or two about things.

Sometimes the only endorsement someone needs is “I read their stuff and they don’t seem to be an axe murderer.”

Sarah Constantin: The most awful stories I heard about “he said this and never got a grant again” were criticisms of the scientific establishment, of funders, or regulators.

Tame stuff like “there’s too much bureaucracy” or “science should be non-commercial.”

In terms of talking to internet weirdos who reach out, I can’t always engage, especially not at length, but I try to help when I can.

I don’t see enough consideration of ‘goal factoring’ around the testing process and the FDA. As in, doing tests has two distinct purposes, that are less linked than you’d hope.

Finding out if and in what ways the drug is safe and effective, or not.

Providing the legal evidence to continue testing, and ultimately to sell your drug.

If you outright knew the answer to #1, that would cut your effective costs for #2 dramatically, because now you only have to test one drug to find one success, whereas right now most drugs we test fail. So the underrated thing to do, even though it is a bit slower, is to do #1 first. As in, you gather strong Bayesian evidence on whether your drug works, however necessary and likely with a lot of AI help, then only after you know this do you go through formal channels and tests in America. I will keep periodically pointing this out in the hopes people listen.

Why do clinical trials in America cost a median of $40,000 per enrollee? Alex Tabarrok points us to an interview with Eli Lilly CEO Dave Ricks. There are a lot of factors making the situation quite bad.

Alex Tabarrok: One point is obvious once you hear it: Sponsors must provide high-end care to trial participants–thus because U.S. health care is expensive, US clinical trials are expensive. Clinical trial costs are lower in other countries because health care costs are lower in other countries but a surprising consequence is that it’s also easier to recruit patients in other countries because sponsors can offer them care that’s clearly better than what they normally receive. In the US, baseline care is already so good, at least at major hospital centers where you want to run clinical trials, that it’s more difficult to recruit patients.

Add in IRB friction and other recruitment problems, and U.S. trial costs climb fast.

See also Chertman and Teslo at IFP who have a lot of excellent material on clinical trial abundance.

FDA Delenda Est

Anatoly Karlin: Lilly stopped one of two trials of bimagrumab, a drug that preserves muscle mass during weight loss, after new FDA guidance suggested that body composition effects wouldn’t be enough for approval, but would need to show incremental weight loss beyond the GLPs.

GLP-1s help you lose weight. The biggest downside is potential loss of muscle composition. But the FDA has decided that fixing this problem is not good enough, and they won’t approve a new drug that is strictly better on an important metric than an existing drug. Not that they won’t recommend it, that they won’t approve it. As in, it’s strictly better, but it’s not enough strictly better in the ways they think count, so that’s a banning.

Which is all Obvious Nonsense and will make people’s lives much worse, as some lose muscle mass, others put in a lot more stress and effort to not lose it, and others don’t take the GLP-1 and thus lose the weight.

The second best answer is that things like muscle loss prevention should count as superior endpoints.

The first best answer is that ‘superiority’ is a deeply stupid requirement. If you have drug [A] that does [X], and then I have drug [B] that also does [X] about as well, the existence of [A] should not mean we ban [B]. That’s crazy.

Uncertainty at the new iteration of the FDA is endangering drug development on top of the FDA’s usual job endangering drug development. You can’t make the huge investments necessary if you are at risk of getting rejected on drugs that have already been approved elsewhere, for reasons you had no ability to anticipate.

It would be good not to have an FDA, or even better to have a much less restrictive FDA. But if we’re not going to relax the rules, incompetence only makes it all worse.

Some good news: The FDA is now ‘open to Bayesian statistical approaches.’ I suspect this only means ‘you can use evidence from Phase 2 in Phase 3’ but it’s great to see them admitting in the announcement that Bayesian is better than frequentist.

Hansonian Medicine

Robin Hanson finds the most Hansoninan Medical study. Amy Finkelstein and Matthew Gentzkow use mover designs to estimate the causal impact of healthcare spending on mortality. They find that extra healthcare spending, on current margins, has slightly negative impact.

Robin Hanson: ”we investigate whether places that increase health care spending also tend to be places that increase health. We find that they do not”

Their point estimate is that residents lose ~5 days of lifespan at age 65 for every 10% increase in medical spending. Standard error of this estimate is ~7 days.

So two sigma (95% confidence level) above the estimate is +9 days of lifespan. Really hard to see that being worth 2% of GDP.

The discussion is frank that this doesn’t rule out that different regions might be providing similar care with different levels of efficiency. In that case, there’s a lot of money to be saved by improving efficiency, but it doesn’t mean care is wasted. There’s also potential selection effects on who moves. You would also want to consider other endpoints beyond mortality, but it’s hard to see those improving much if mortality doesn’t also improve.

Robin Hanson links us to this paper, showing that greater expected pension benefits led to more preventative care, better diagnosis of chronic diseases and improved mortality outcomes. As in, there is a real incentive effect on health, at least at some income levels.

Hospital Strategy 101

Gene Kim offers a writeup of his wife’s hospital experience, explaining some basics of what you need to do to ensure your loved ones get the care they need. Essentially, the Emergency Department is very good at handling things you can handle in the Emergency Department, but the wiring connecting the various departments is often quite poor, so anything else is on you to ensure the coordination, and that information reaches those who need it, figure out where you’re going and how to get there. The good news is that everyone wants it to work out, but no one else is going to step up. It’s on you to ask the questions, share and gather the info and so on. What’s missing here is don’t be afraid to ask LLMs for help too.

Mental Hospital Strategy 101

Being admitted to a mental hospital is very, very bad for you. This is known. It severely disrupts and potentially ruins your life permanently. The two weeks after release from the hospital put you at very high risk of suicide. Having someone committed, even for a few days, is not something to be taken lightly.

That doesn’t mean one should never do it. In sufficiently dire circumstances, where outcomes are going to be terrible no matter what you do, it is still superior to known alternatives. The question is, how dire must be the circumstances to make this true? Are we doing it too often, or not often enough?

A new study measures this by looking at marginal admissions, as different doctors act very differently in marginal cases, allowing us to conduct something remarkably close to an RCT. Such disagreement is very common, 43% of those evaluated for involuntary commitment for the first time fall into this group in the sample.

Even with 7,150 hospitalization decisions, the study’s power is still not what we would like (the results are statistically significant, but not by that much considered individually), but the damage measured is dramatic: The chance of a marginal admit being charged with a violent crime within three months increases from 3.3% to 5.9% if they get admitted, the risk of suicide or death by drug overdose rises from 1.1% to 2.1%.

This matches the associated incentives. If you don’t refer or admit someone at risk, and something goes wrong, you are now blameworthy, and you put yourself in legal jeopardy. If you do refer or admit them, then you wash your hands of the situation, and what happens next is not on you. Thus, you would expect marginal cases to be committed too often, which is what we find here.

It seems reasonable to conclude that the bar for involuntary commitment should be much higher, and along the lines of ‘only do this if there is no doubt and no choice.’

Drugs Are Bad, Mmmkay?

The Lighter Side

The best description I’ve seen of how to think about ‘biological age’ measures:

Ivan: i will only trust your health app’s ‘biological age’ report if it comes bundled with a life insurance offer.

Freddie deBoer has a very strongly worded critique of that "quasi-randomized" involuntary commitment trial that I cannot find right now, but he quite rightly points out that marginal cases of commit / not commit are very far from random and it is very easy to see how non-random factors affect both the outcomes and the probability of being committed -- classic confounding. For something as consequential as mental health and suicide you need a much stronger body of evidence than one poorly controlled quasi-natural experiment

Autism: “insists words have meaning” or “insists words have _one_ meaning”?

Pedantry may be a symptom too :-|