Occupational Licensing Roundup #1

We’re coming out firmly against it.

Our attitude:

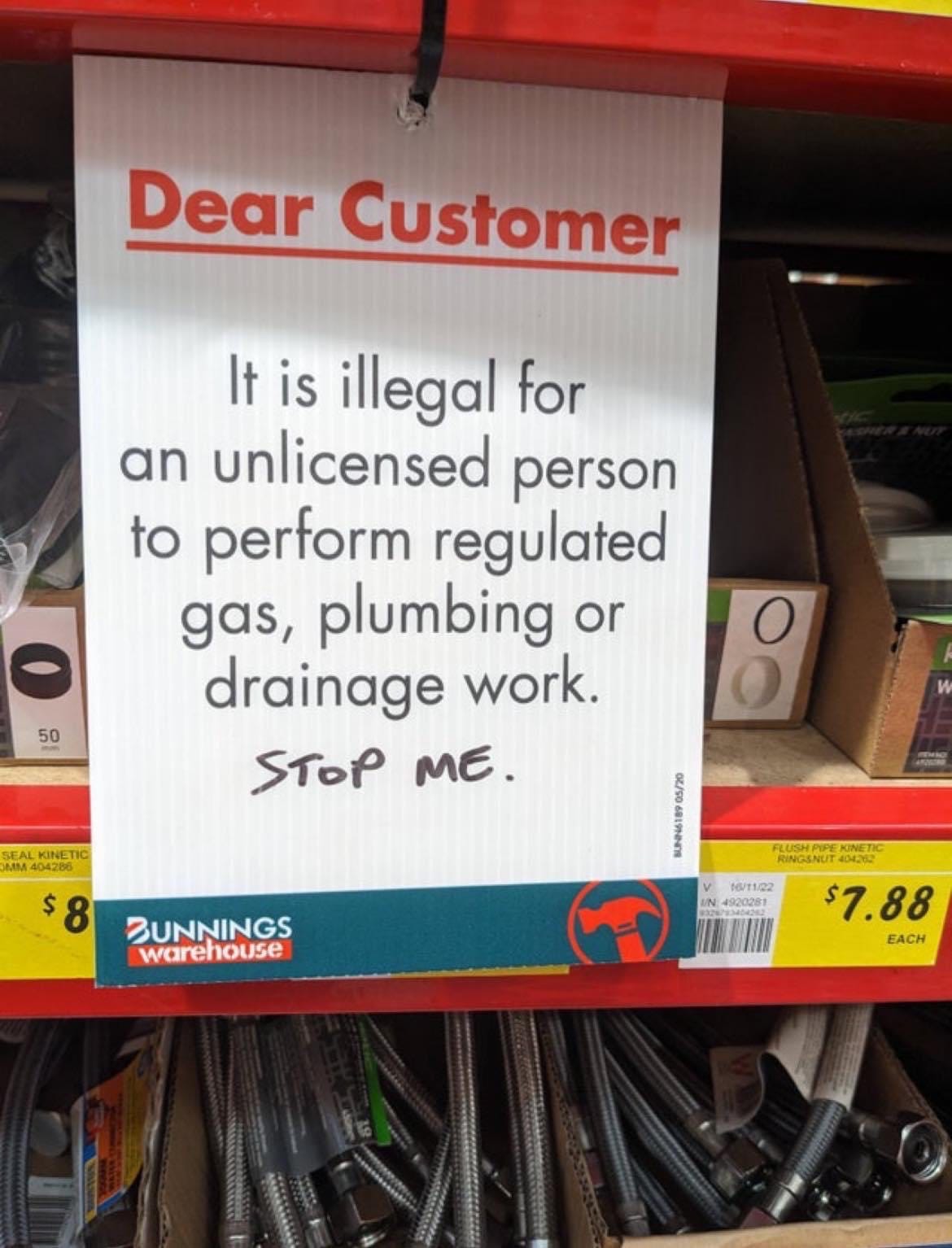

The customer is always right. Yes, you should go ahead and fix your own damn pipes if you know how to do that, and ignore anyone who tries to tell you different. And if you don’t know how to do it, well, it’s at your own risk.

With notably rare exceptions, it should be the same for everything else.

I’ve been collecting these for a while. It’s time.

Campaign Talk

Harris-Walz platform includes a little occupational licensing reform, as a treat.

Universal Effects and Recognition

Ohio’s ‘universal licensing’ law has a big time innovation, which is that work experience outside the state actually exists and can be used to get a license (WSJ).

Occupational licensing decreases the number of Black men in licensed professions by up to 19%, and the number of Black women up to 22%. There is also the headline finding, which is that overall labor supply is reduced 17%-27%. Hopefully this can defeat some talking points or get through some of the damage being done.

Erica Jedynak: 26 states have joined the movement of significant occupational licensing reform - removing government barriers so more Americans can land their dream job. To all the allies part of the original OL coalition, thank you!

Knee Regulatory Research Center: Universal licensing recognition is a growing labor market reform for an easier transition of occupation licenses to new states. A new report from the Knee Center shows 26 states have passed universal recognition policies since 2013. Read more here.

This is really great, everyone needs to get on this to the maximum extent possible.

Libby Jamison: Lots of support for license portability! “About 83% of 848 registered voters surveyed nationwide said they support rules that allow the use of the licenses wherever military family members may move in the U.S.”

The obvious follow up is indeed ‘why only military’? License portability should be universal.

25% of Colorado jobs require a government license. They are at least opening up those jobs to some of the people with criminal records after three years via House Bill 1004. Better yet, we could scrap the requirements entirely.

Podcast on Utah’s approach to occupational licensing reform, based on requiring reviews. I am curious how much this ends up improving things.

To avoid a publication bias style problem I will note I am unconvinced by the paper from Blair and Fisher that notes Angi lead acceptance rates are 21% lower in the presence of occupational licensing requirements, which they attribute to lack of available supply. The problem is that this could be a reflection of things such as lower quality, where low quality providers accept leads a lot while high quality ones can afford to pick and choose. Thus, while I am in general highly convinced such requirements are counterproductive, I don’t think this provides strong additional evidence of that.

I like this new framing from The Atlantic, calling occupational licensing ‘permission slip culture.’

Construction

Connecticut requires occupational licensing to work ‘in the trades’ such as construction, which is leading to a worker shortage.

Doctors and Nurses

Doctors from abroad permitted to practice in Tennessee starting 2025, other states following suit. Yes, this is the right thing to do given a shortage, also without a shortage. Presumably this will form a natural experiment that shows it goes great, and the AMA will fight with all its might to stop it from spreading.

This seems pretty great:

Scott Lincicome: New paper: State laws granting nurse practitioners full practice authority (FPA) "reduces total health care costs for diabetics by approximately 20% in urban areas and reduces rural usage of advanced medical services for diabetics by about 10%."

That is one of those effect sizes so big it is suspicious. Hot damn.

Florists

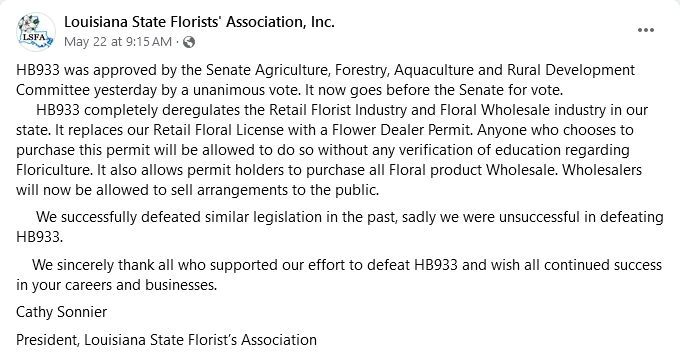

We won a local victory on this one.

Shoshana Weissman: HOLY SHIT IT FINALLY HAPPENED TELL THE OTHERS

No more florist licensing in Louisiana!

I'm gonna have to make an example out of some other state!

The origins of reform have a really horrible story.

Elderly widow Sandy Meadows died in poverty because the government wouldn't let her be a florist.

After Meadows’ husband passed away, she had little money or education. She found a way to support herself by managing the floral department of a local grocery — until Louisiana Horticulture Commission threatened to shut down it down unless it hired a licensed florist.

The exam required they arrange 4 bouquets in 4 hours. The results were judged by a panel of licensed Louisiana florists, who obv viewed applicants as competitors. The passage rates for the exam were below 50%; even longtime florists often failed it.

"One licensed florist in the state described the test as nothing more than a “hazing process.” Ultimately, because she could not pass the exam, the grocery store had to let Meadows go."

You have to admire the chutzpah of such groups. Well, no you don’t, but you should.

Chris Retford: Someone should send them flowers.

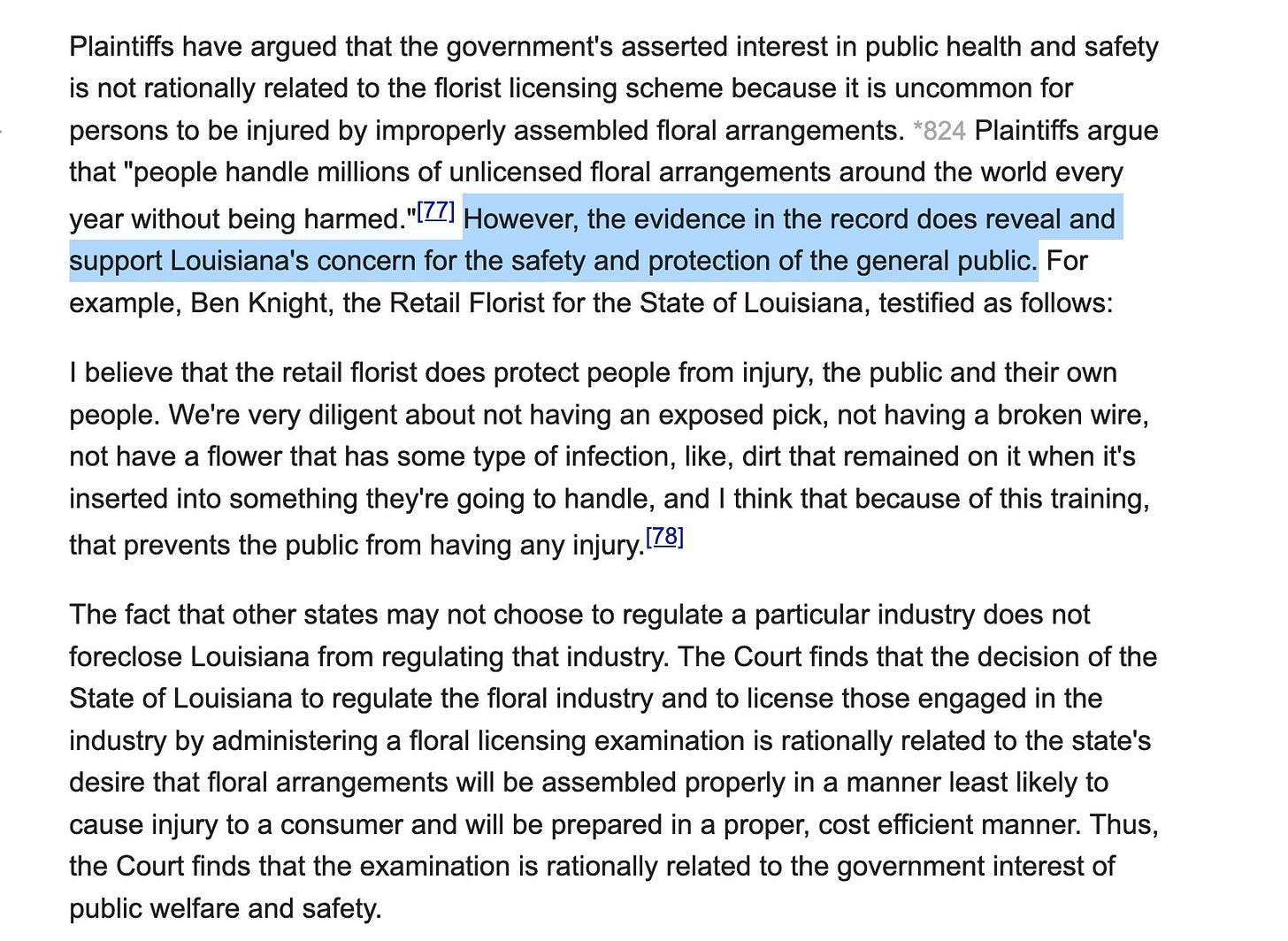

Clark Neily: If you follow me or have read my book, Terms of Engagement, you may think I heap excessive scorn on the rational basis test. But I assure you that's metaphysically impossible—as this excerpt from the DCT opinion *upholding* the florist-licensing law shows.

Seriously, burn it all to the ground. No occupational licenses for anything. Nuke from orbit. Only way to be sure. Replace with insurance requirements where it feels necessary. If we make a handful of mistakes that way? Well, that is a price I am willing to pay.

Fortune Telling

Pennsylvania (unexpectedly?) outlaws fortune telling.

The incident also drew attention to the fact that despite its widespread popularity, fortune-telling and related arts are indeed illegal in Pennsylvania, punishable by 6-12 months in jail and a $2,500 fine. Pennsylvania statute forbids residents from “pretend[ing] for gain or lucre, to tell fortunes or predict future events, by cards, tokens, the inspection of the head or hands of any person,” and from promising “to stop bad luck, or to give good luck … or to win the affection of a person, or to make one person marry another.”

Selling astrology readings and tarot readings are illegal, too.

The standard defense is to say the readings are ‘for entertainment purposes only.’

Except, no. They’re not.

There is a strong argument for the level of enforcement we see described here. The whole thing is centrally a fraud. Most of the time it is a harmless and fun one that many people get something out of. There are also ways to use the tools responsibly. You can get real utility, as I have, out of a tarot reading by using it to figure out what you really think and explore possibilities. Cold reading can allow the providing of useful advice, and is a fun game. Magick is not what its proponents claim to outsiders, but it is less fake than most people reading this think.

However, this goes hand in hand with actually malicious fraud, as the way (at least) many fortune-tellers and other such folks make most of their money is to sell high priced services to vulnerable victims who they very much defraud and prey upon.

So the idea is that when that happens, and it comes to the authorities’ attention, they can reliably crack down without having a high burden of proof. If no one complains, everything is fine, police have better things to do.

Therefore customers hold the balance of power, and have to be treated well. Not the first best solution to the problem, but it mostly works.

Hair

By default you get things like this, and they say it like they are proud of it.

Governor Ned Lamont (D-Connecticut): By requiring inclusive hair education for cosmetology licenses, we can ensure that all hair types and textures are properly cared for. This law supports our diverse communities and sets a new standard for excellence in beauty services. I'm proud Connecticut is leading the way.

St. Louis has signed a bill legalizing cutting hair after 6:30pm. Good for St. Louis, but that just raises further questions.

Olivia French in DC, who was appointed by Mayor Bowser, has been ‘selling cosmetology and barber licenses to unqualified students for thousands of dollars.’

Four notes.

‘Unqualified’ students? That’s not a thing, this is hair.

Good.

This is an estimate of how much value is lost when we require these courses.

If you elect a Mayor Bowser, I don’t really know what you were expecting.

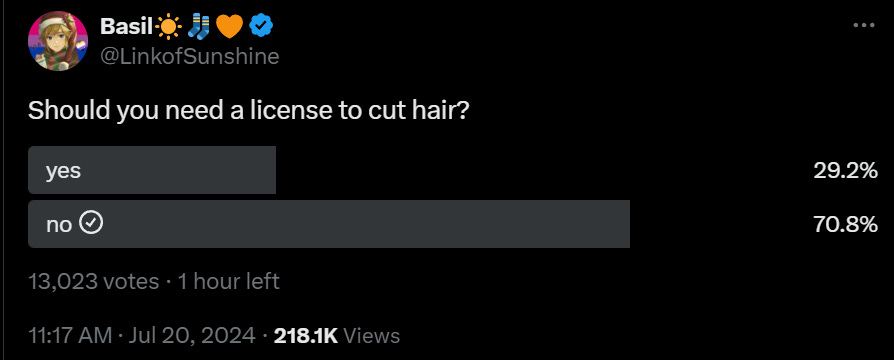

Do people believe in the need for all this nonsense?

Yes. They really, really do. Not all of them, but a remarkable fraction of them.

It was up at 40% earlier, before it was circulating in different circles.

Emmett Shear: The replies to this thread blow my mind. People legit believe the state needs to protect them from bad haircuts by ensuring hair stylists meet training standards. I’ve never seen the nanny-state mind virus (timorus overprotectionis) on clearer display.

Here are the top 4 comments in order:

Capybara Enjoyer: I don’t understand why barbers are always the first criticism of occupational licensing, there’s a lot of potential chemical and hygiene issues in the job. Some states might overdo it, but i don’t get why this is a job used to highlight why licensing is bad. Infections are risky.

Jon Swifty: My girlfriend tried cutting my hair once and I called the cops on her. Gotta stay safe, I almost experienced something without the explicit consent of the government.

Andrew Works: Seeing as it could impact one’s life (such as looking unprofessional during a job interview, I say yes.

Jake Thompson: Yes, but only if you are giving shaves. I am of the opinion that barbering needs a license because like you could literally kill someone. We need to prevent more Sweeney Todd situations.

The reason to require a license is if reputational effects don’t work…

Among the Wildflowers: There is NO reason we should require cosmetologists to have a license.

Trust me - if someone fucks up a woman’s haircut, everyone within a ten-mile radius will know about it. We don’t need a license to prove we can cut hair.

CUT IT OUT.

Alas, instead, Michigan is going to make things even worse.

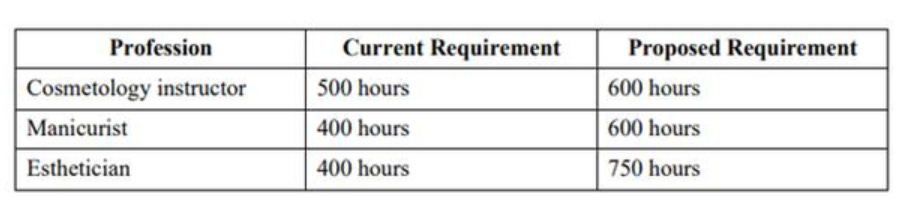

It seems that there is a federal rule that to get financial aid for your unnecessary occupational licensing training, the hours of training from the program have to match the required hours. That’s an obvious sign that no one cares about actually teaching things - too few hours is illegal, and also too many is almost de facto illegal too. So the schools involved that were training for ‘too many’ hours threw a fit, and lawmakers caved, increasing the requirements to match, a pure case of That Which Is Not Forbidden is Compulsory, and That Which Is Not Compulsory is Forbidden.

Needless to say, none of this makes any sense whatsoever. 600 hours to become a Manicurist? What? New York requires 250, even that seems utterly crazy. I don’t even know what the theory of something going wrong is, beyond ‘our wages might fall.’

Lawyers

It is bold to write the case that The World Needs More Lawyers. Given what I keep paying when I need lawyers in order to safely do regular business, one could make a case. What we need is not more lawyers. We need more ability to do legal work.

One way to do that is more lawyers. The post has better suggestions.

Another strategy is to let lawyers more easily move jurisdictions, or change the requirements to eliminate counterproductive requirements, such as those that discourage seeking professional help with mental health and pointless-in-practice CLE requirements. Another is to open up more of the basic work to other trained professionals (or where feasible AIs and other computer programs).

Another is allowing non-lawyers to own legal service companies, which Arizona has experimented with thanks to a court ruling, with good results. We have a lot of knobs we could turn, if the lawyers who run our government wanted the price of legal services to go down rather than go up.

Four states have stopped requiring the bar exam to practice law. This is being reported as a DEI-run-rampant story, whereas it is actually a DEI-allows-sanity story. Yes, obviously the bar exam like all licensing requirements is an ‘unnecessary block’ to Black individuals becoming attorneys, because it is such a block for all people looking to become attorneys.

Is it ‘disproportionate’? I don’t care. What matters are results, not rhetoric. I am totally fine with using ‘unnecessary regulation X is bad for group Y’ as a reason to get rid of unnecessary regulation X that is bad for everyone. More of this, please.

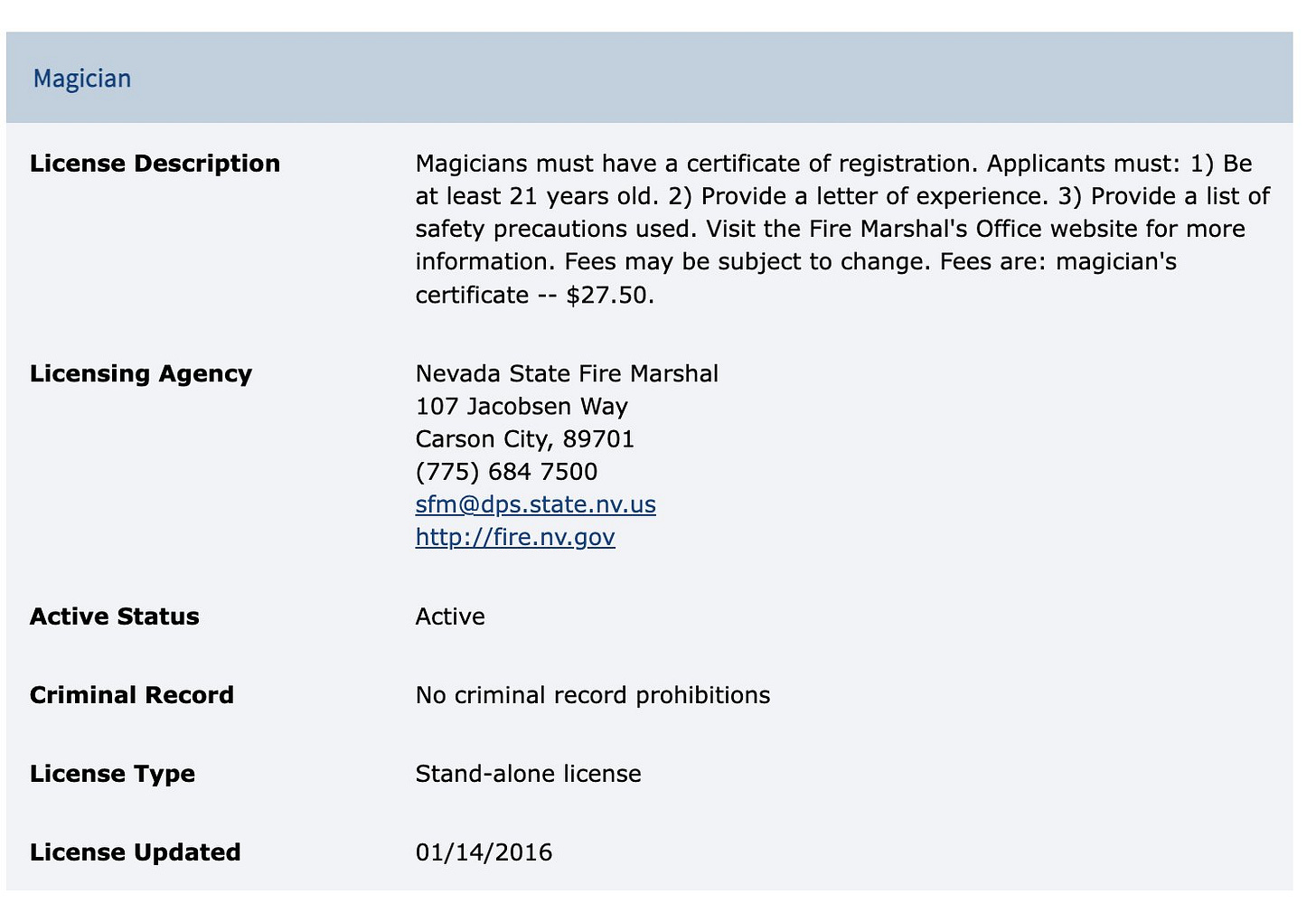

Magicians

Let’s see them get out of this one.

Shoshana Weissmann: Someone asked me

I can't believe this exists

OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING FOR MAGICIANS

Military Spouses

Colorado signs bill for licensing recognition for military spouses, making it easy to get their out-of-state credentials respected. The obvious question is why not do this for everyone, but I’ll take it.

It works. Full recognition of military spouse licenses for registered nurses increases the probability of employment mobility by around 12%, while more restrictive reforms have the opposite effect. Obviously if you make licenses more portable employment will be more portable. The effect size being large is worth confirming though. The question is, what about all those dastardly nurses who are truly qualified to work in Ohio but not in Arkansas, or vice versa?

Mountain Climbing

Shoshana Weissmann: So this is my new enemy I guess.

AP: The youngest woman to climb all of the world's 14 tallest peaks calls for novices to be regulated.

A British mountaineer who set the record as the youngest female to climb all the 14 tallest mountains in the world said Thursday that inexperienced climbers should not be allowed to climb the highest peaks because they run the risk of endangering their lives and others.

This isn’t an unusually crazy or stupid proposal. The other occupational licenses that actually exist are often exactly this crazy or stypid.

Music

I… think… this is real? A law introduced in Kentucky to license music therapists? As in, people who play recorded music?

Nurses

Preston Cooper: All on board with banning legacy admissions but TBH this probably would have been the more consequential California higher ed policy change.

Quick hits: Newsom vetoed two bills that would have allowed some community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees in nursing, a contentious idea in the state’s rigid higher-ed system despite nursing shortages.

Preston Cooper: "The California State University opposes both bills, viewing them as undermining a promise lawmakers made two years ago that community colleges wouldn’t issue bachelor’s degrees that duplicate existing Cal State programs."

Cartels gonna cartel.

Cal Matters: Update: On Sept. 27, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced he had vetoed both bills. In his veto messages, Newsom urged community colleges to work with colleges and universities that already issue bachelor's degrees in nursing programs. He said he worried that these bills to allow community colleges to award their own bachelor's degrees in nursing would undermine those existing partnerships.

He also noted that the state has recently given both community colleges and the California State University more freedom to create new degree programs and that "a pause should be taken to understand their full impact before additional authorities are granted."

Quote that the next time someone says you should take Newsom’s veto explanations as words that have meaning.

Physical Therapists

New York is going to require physical therapists to hold doctorates (60 more credits than previously required). The reasons given are only slightly paraphrased when I summarize them as ‘rent seeking.’ The insiders told us to restrict market entry.

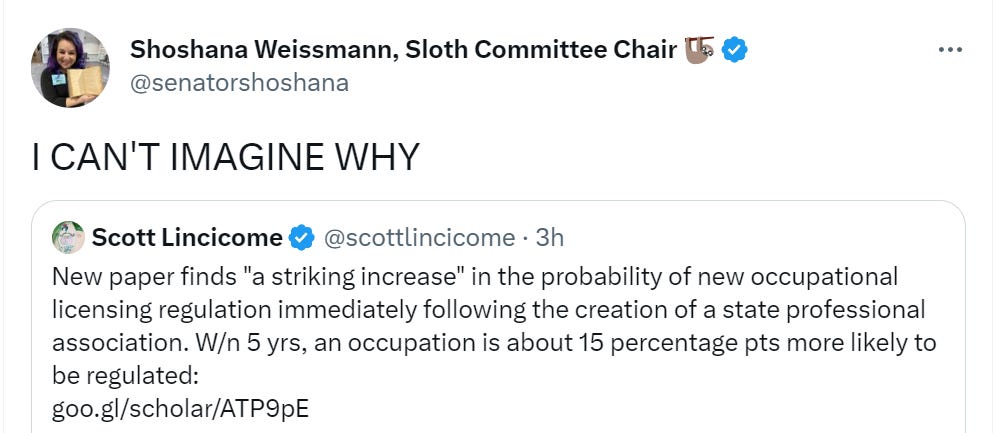

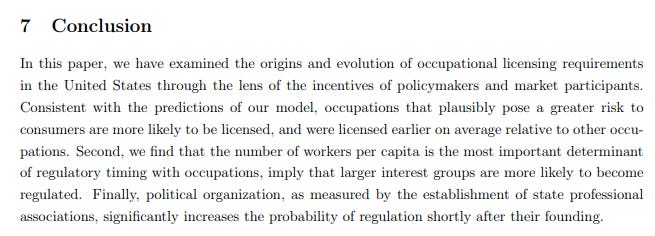

Whatever Could Be Causing All This Rent Seeking

Masks off, how do you do, fellow rent seekers:

Shoshana Weissmann: Actual inbox from someone who runs license testing in FL: “There is nothing wrong keeping people from other states from stealing construction business from already established, licensed and insured Florida contractors.”

YIKES.

Well, then.

Adam Morris: After Harvey, there were people whose houses weren’t fixed for 2-3 years in part because there weren’t enough contractors available to handle all the work.

After a hurricane, “not enough work for local contractors to do” is not the problem.

Tornado Relief

Volunteer Tree-Trimmer Fined $275, Told to Leave Minneapolis, After Helping Tornado Victims Outside His Assigned Area

Even if we are not going to fix occupational licensing in general we should do it in emergency situations via permanent known rules that get triggered when there is a hurricane or other similar event.

Pretty Much Everything

Legal Style Blog: The list of businesses which require a licence in Los Angeles County is hilariously specific. Bookstores, rifle ranges, ambulettes, hog ranches, taxi dancers (are there any in 2024?), peddlers, bottlewashing, raw horsemeat…

Another comment: wouldn't, in the case of law, doing away with the education requirement and keeping the exam be the fairer and less distortionary policy? The DEI nonsense aspect of it is that law school might still be required (i.e. someone sitting through 3 years of classes, which are not quality-controlled) and no independent, objective measure is not required - meaning that people who can't hack it on the test get a workaround. Tests or apprenticeships for skilled professions seem like reasonable compromises.

The Bar Exam is good, actually. I think the alternative, diploma privilege, is significantly worse and if we got rid of one I'd get rid of the law school graduation requirement before the bar exam.

We need some barriers to entry.

Let's just start off with what lawyers do. Occupational regulation for florists ought to be less than that for neurosurgeons; where does law fall? Should we regulate entry at all?

Lawyers have different skills that apply to different types of work. Trust and estates lawyers need to know their field well, but don't need a lot of courtroom moxie. Criminal lawyers on both sides are sometimes not technically expert, but need to be good in court and really desperately need to be good at evidence. Civil lawyers need strong research skills. Family law lawyers need to be able to navigate both the law and their clients' emotional states. Some states require a real estate lawyer to buy or sell real estate; this tends to be pro forma work and the systemic losses almost certainly exceed the gains from such laws.

If you let anyone be a lawyer, the courts will be clogged with nuisances and the already-difficult efforts to find a good lawyer head to hopelessness. This isn't dog-walking or hair-braiding; neither is it knee surgery. If you (you=reader here, not you=anyone) give me nine months, I could make you a functional lawyer in one field. But people who represent themselves often violate basic rules and use up a ton of court time. (This isn't always true, and some hearings are basically designed to handle people representing themselves - small claims, restraining orders, sometimes child support compliance, etc. Plus some who represent themselves are very good.)

We probably don't want (more) people convicted of crimes because their lawyers were bad. We don't want kids in hazardous situations. Lawyering matters.

Very few lawyers are genuinely competent in multiple fields. Lawyers who decide to take that one case outside their field are typically making a serious error. But both law school and the bar are designed for a much wider range of knowledge.

The usual take of the bar abolitionists is that the exam does not improve lawyering. To me, the most solid of the critiques is that the bar isn't like practicing law because lawyering is open-book - I mean, sometimes I don't know things. This is a crucial skill, and lawyering is largely an open book exam.

But not totally. If you're doing in-court hearings, you'd best know your evidence code. When surprises strike, what do you do? What motions are available? What are the basic rules? What are the procedural rules of court that will bite you if you disobey them? When the judge is making his own motion - required by law - to dismiss some defendants, maybe you've done something wrong.

The bar exam is written differently in different jurisdictions and sets a different standard in different jurisdictions. I view this as (probably) a feature; states ought to be working toward maximizing their results.

And, look, it's undeniable that people fail the bar exam who would make perfectly fine lawyers.

The former elected DA of Near-me County failed the bar six times; I know this because this is one of her go-to stories. A Stanford dean failed. People fail. And some of them doubtless shouldn't fail; the bar is a test of minimum competence - can you hold some information in your head and answer questions about it? Can you analyze your way accurately? But people who are highly qualified nonetheless fail, and people who would have become assets to the bar fail and can't be attorneys. This is bad.

Further, the bar is likely a poor proxy for determining if you are going to steal your clients' money. Some people pass the bar who are dreadful.

But the alternative to bar exams is nothing - which I reject - or diploma privilege. (Or some very seldom used apprenticeship routes.)

Is law school really a better proxy?

I'd tell you what the usual argument is for law school as better than the bar, but there isn't a clearly articulated one I could find. This is likely because the presumption of law school remains very strong. Law school is supposed to teach analytical thinking and also shows a certain degree of diligence. But if you have a proper test, you can test analytical thinking and sufficient diligence to learn the material on the test. Law schools have different goals depending on their student population, but if the goal is "competence at lawyering," maybe [redacted famous Harvard professor - not that one, and no not that one either] shouldn't be teaching you.

I think the best argument is that law school ought to teach some degree of oral advocacy and also that the manner of legal thinking is ingrained in future lawyers. Getting through three (or, if going to my alma mater Bob's Waffles and Law - no law parking during breakfast hours - four) years of doing something and passing tests shows a certain interest in the craft. Persistence and repeatability surely matter. I have very little doubt that law school is a benefit and in many cases a very substantial benefit.

But at what cost? Are you telling me that a person *who could ace the bar exam* wouldn't have more benefit from three years as a lawyer as they would in law school? That's also comfortably in the six digits as far as financial situation. (I know judges with law school debt.)

Further, if you have diploma privilege, are you going to give it to all schools? Are you going to close down California's system of slightly dodgy, sometimes cheap, law schools? If you create a diploma privilege, you can't let these schools grant you lawyerhood if you want any quality control - some of them are bad. Diploma privilege necessarily requires strong accreditation procedures.

If you're going to have a gateway to the profession, both an exam and law school provide some showing of competence. Providing a bonus to law school graduates on the bar exam is probably a plus position. But diploma privilege is likely to lead to some greater abuses.

Wisconsin has diploma privilege, but the express reason for that is to prevent Wisconsonites from moving. It's also only for in-state schools. Your U. Chicago law degree can go in the trash, but you're in if you went to Marquette. Let's not pretend this is designed as anything other than in-state protectionism.

Thirty-year-olds are better lawyers than 25-year-olds, who would be better than 21-year-olds if there were a bunch of 21-year-old lawyers. Law school delays entry into the profession until the reaching of a more mature age. But my suggestion wouldn't result in ordinary 21-year-olds being lawyers. Further, they'd have nine years experience when they were 30, and most would be specialists.

Finally, note the systemic incentives. Law schools have a strong incentive to maximize the value of law schools. They're not going to endorse this. Lawyers generally have an interest in reducing entry into the field. Optimizing for entry can't be open season (says me), so we have to find ways to properly screen. Neither law school nor the bar exam is a perfect solution, but privileging educational attainment over actual knowledge doesn't sound like the right thing to do.

Limited purpose licenses for narrow areas of law are probably a good thing but I think I've run rather long as it is.

Of course, that's just my opinion. I could be wrong.