On Robin Hanson's "Social Proof, but of What?"

Response Post to (Overcoming Bias): Social Proof, But of What?

Epistemic Status: It seemed worth writing a long post but not a short one, so I saved time and wrote a long one. Feel free to skip this if it does not seem interesting to you.

It seems worthwhile to closely examine the first two paragraphs of Robin Hanson’s recent post, except I will replace his A and B with X and Y because this is a classic Robin “X is not about Y” claim (“Talk isn’t about info”):

People tend to (say they) believe what they expect that others around them will soon (say they) believe. Why? Two obvious theories:

X) What others say they believe embodies info about reality,

Y) Key audiences respect us more when we agree with them.

Can data distinguish these theories? Consider a few examples.

Robin goes on to consider examples that he suggests are better explained by Y than by X.

I noticed instinctively that this framing felt like a trick. After analyzing this instinct, I noticed it was because Y was a very strange particular hypothesis to privilege. If I was writing this post in a ‘write through to think it through’ mode, I would have said something like this (without consciously considering the examples Robin gives, although I did skim them on a previous day before writing this list, and giving myself about 30 minutes):

People tend to (say they) believe what they expect that others around them will soon (say they) believe. Why? I see three classes of reasons they might do this:

X) What others say they believe embodies info about reality.

X1) It is likely to be an accurate map.

X2) Even if inaccurate, it is likely to be a locally useful wrong map.

X3) You might choose to be around those for which X1+X2 are true.

X4) You have more exposure to the expressed beliefs of those around you than of others, and of their justifications for those beliefs, and often they are motivated to convince you to share those beliefs.

X5) You likely share much of the same cultural background, skills, knowledge, contacts and information flows as those around you, and you often combine such things. Such resulting beliefs not being highly correlated would be very surprising.

X6) X4-X5, with explicit information cascades, whether or not the information in question is accurate.

X7) Skin in the game. Those around you are in a position where you can reward or punish them, so if believing the things they say hurts you, they could worry you could dislike that and decide to punish them, or if it helps you, you might reward them. This makes their claims more credible as things that would be useful.

Y) It is useful to believe the things others around you say they believe.

Y1) Your behavior will be more predictable to those around you, and the behavior of others around you will be more predictable to you.

Y2) Your behavior can be justified by beliefs verbally backed by those around you, but other beliefs cannot as easily do this. So you want to believe Y so you will take actions that Y justifies.

Y3) If you believe what others around you do not believe, and act on that basis or claim to, that is an active choice, activating Asymmetric Justice and making you responsible for all resulting harms without getting credit for resulting benefits.

Y4) Belief makes it easier to credibly say, or less painful to say, that you believe what others around you believe, for reasons of class Z. If you don’t believe those things, but only say you do, people are often good at detecting that, and your actions or other details may reveal the truth.

Z) It is useful to say that you believe the things others around you say they believe.

Z1) People respect you more when you agree with them.

Z2) People will also think you are smarter, more trustworthy, more ‘in the loop’ or ‘in the know’, more savvy (especially if you anticipate and say you believe the thing before others say it), and so on.

Z3) People will directly reward you slash not punish you, including to demonstrate their own beliefs

Z4) Meta-Z3, people will expect to be rewarded or punished based on associating with people who say they believe what others around them believe, and so on.

Z5) People say they believe these things so that others around them will say they believe it, which means they prefer it if you do. Perhaps they have good reasons for this. Perhaps the good reason is that it benefits them, and it is good when people around you think you are doing things that benefit them. You will be seen as a better potential ally if you are expected to say you believe what others around you say they believe, especially if you show willingness to change your answers to match those of others.

Z6) If you don’t say such things, for some values of such things, people will think you are stupid or even various levels of evil or insane. You could even be exiled from the group.

Z7) If you say you believe other things, that becomes the topic that others will focus on, you will have to defend that, perhaps revealing other things you believe or say you believe, that others around you do not say they believe. Essentialism could easily set in. Where does it stop?

Z8) Saying you believe different things makes you stick out. Most people would rather conform most of the time, in all ways. You have evidence that it is safe to say the thing others are saying or are going to say, and you lack evidence about alternative things you might say. Why risk it?

Z9) If you say you believe something different from others around you, but it is revealed you acted in a way that contradicts that, you are a hypocrite and will be punished. However, if you say you believe what everyone else believes, and act in a way that contradicts that, you are much less likely to be held to account at each step.

Z10) Meta-Z. If you show you do not care about saying you believe what others say you believe, that triggers all of this on another level, and so on.

Reading a draft, Ben Pace noted an additional explanation Z11, which is that reasons are incompatible with improv (“Yes, and”, etc), and many interactions are essentially improv.

(Note: Z3 and Z6 do on reflection seem meaningfully different. Z3 is the expectation of limited-scope incremental tit-for-tat-style rewards and punishments, whereas Z6 involves essentialism (e.g. “This person is an X”) and potential consequences such as exile, imprisonment in a psychiatric facility or a burning at the stake as a heretic.)

We can summarize this as:

X-reasons: Updating your beliefs for epistemic reasons

Y-reasons: Updating your beliefs for pragmatic reasons

Z-reasons: Updating your expressed beliefs for signaling reasons

Robin’s claim is explicitly Z1, and mostly includes Z2. It could be said to implicitly include a bunch of others to varying degrees, but still seems like a highly incomplete subset of the class of explanations ‘saying such things is useful regardless of what is true or what you believe,’ as opposed to the categories ‘believing such things is useful regardless of what you say you believe or what is true’ or ‘such things are likely to be true or at least locally less wrong than available alternatives, regardless of whether it is useful to believe it or say that you believe it.’

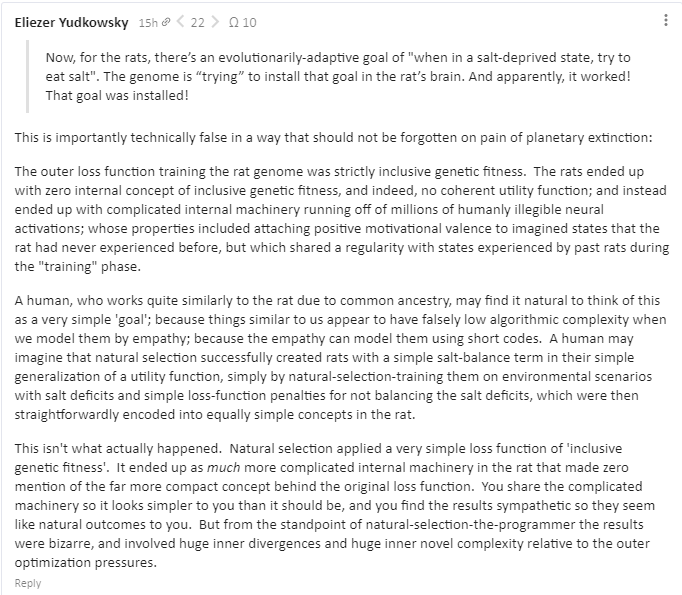

Before I begin, I’d also note that this type of discussion often includes the implicit assumption that people believe things, or that those beliefs cause people to do things, or that they say things because they believe them, or that people choose their beliefs or actions because of reasons and an aim to achieve some goal. Such frames can be useful, but also are importantly technically wrong, and in some situations and for some people, including some important people and situations, they are not good models. To quote a recent Eliezer Yudkowsky comment on a post about rat behaviors:

In light of all that, let’s consider Robin’s examples, and see what is going on.

Case C (we’ll skip A and B to avoid confusion with Robin’s original A+B):

First, consider the example that in most organizations, lower level folks eagerly seek “advice” from upper management. Except that when such managers announce their plan to retire soon, lower folks immediately become less interested in their advice. Manager wisdom stays the same, but the consensus on how much others will defer to what they say collapses immediately.

Seeking advice from upper management serves many purposes, including many of the items on the brainstormed lists above. Let’s go through them.

One purpose is because of (the extended) theory X, that the information might be true, true and useful, or false but in a way that is functionally useful. At first glance, this theory is taking a hit here. But can it explain the observation?

I can think of many reasons to expect advice from the soon to be retired to be less accurate. These come mostly from motivation X3 and X7, resulting in X1 and X2, and the expectation that information from this source is now less reliable.

C1) Once someone announces retirement, they are no longer going to have as high a value on information, especially information about the future. If one is going to be relaxing on a beach a year from now with no further ties to the company, why should you pay attention to internal company politics, or which projects seem more promising?

C2) Once someone announces retirement, they no longer care as much about the truth or usefulness of the information they provide to you. If I ask you whether it is going to rain tomorrow and you say no, and then it rains, I can blame you for giving me bad info. But if you are on a far away beach tomorrow and never see me or anyone I know again, you don’t care about that. I might tell you it won’t rain purely because that will make my next five minutes more pleasant. So it goes with advice. Someone who won’t be around has no skin in the game.

C3) Same logic as C2, but also such a person will not want you as an ally. People typically want their allies and potential future allies to succeed so they can be more powerful, and want such people to be positively inclined towards them, both of which suggest giving good advice. Thus, not being around in the future makes their advice less reliable (as opposed to asking them being less useful, which we’ll get to in a bit).

C4) Same logic again, but about goals and perspectives rather than their incentives or info. Someone in the mindset of seeking success will be more likely to provide helpful advice for someone looking to succeed. Once someone no longer has that mindset, their advice will become less accurate.

C5) They are retiring. This could be seen as evidence of unreliability, in addition to its cause. Several ways. Failure causes retirement. A person often retires because their skills and knowledge and political power have decayed, or because their performance was poor. Perhaps this is old age, perhaps this is failure to notice which skills and knowledge and angles of political power are important. Perhaps this exposed weakness that was always there. Either way, those with better advice to give would have been less likely to announce retirement.

C6) Retiring is known to make people seek you out less for advice. Thus, if someone had good advice and the desire to share it, that is a motivation to not announce retirement. Since they announced retirement anyway, this suggests they are not so interested in giving such advice.

This all seems like it is certainly sufficient to explain seeking out advice of the soon-to-be-retired less than those who are not going to be retired soon. There are also lots of good explanations for this change in advice seeking that come from other motivations, which certainly contribute. But even before listing those, it is worth noting here that it does not seem that this example differentiates much between X-style causes, Y-style causes and Z-style causes, because all of them point in the same direction.

If you have a choice of many from whom to seek advice, and only need seek advice from a few of them, then even a small consideration can shift much advice seeking from one set of sources to another.

There is the opposite case that one might make, which is that without further skin in the game, a soon to be retired person could now speak honestly and give objective advice. You would not need to worry as much about them being motivated by what would be good for them, or what they felt the ability to tell you, and they may have a superior perspective on everything.

I do think this is important, and that often one should get some of one’s advice from such sources when one’s motivation is seeking truthful and useful advice. Or even more than that, when one wants to decompose the advice of insiders into the part that is primarily truthful and useful versus the part that is primarily other things, or otherwise provide a sanity check. But this mostly only works if one can find a source that can be trusted to both still have relevant information, and also to be motivated to be helpful. Finding such sources is extremely valuable. Most higher level people who are soon to retire do not count as such a source.

For completeness, let’s compare to other motivations for this change, and note that aside from X4-X5-X6 which are kind of distinct from everything else because they aren’t talking about motivations, every single thing on the list points in the direction of what we observe:

Y1/Y4->C7) Part of advice is learning to model others, and allowing others to model you, and matching your belief statements with theirs. Learning to model someone who is leaving isn’t as useful. You don’t care about modeling or matching them in particular, nor letting them in particular model or match you, and they are now less correlated with similar others. Plus if others are seeking their advice less, then seeking their advice makes you less predictable and on point for that reason as well.

Y2/Y3->C8) If you seek advice from someone, you can use that to justify your behaviors (and stated beliefs). This is a lot harder to do when the person is gone. Taking advice from someone no longer there, that is different from the advice of those still around you, seems like the kind of active choice that makes you eligible for blame assignment and Asymmetric Justice. Plus your claim to be following such advice is unreliable at best, as you could make up any such advice claims you wanted.

Z1/Z2/Z3/Z4/Z10->C9) This certainly fits. To the extent you want to use agreement to earn respect, you want to choose those whose respect you want. Same with other considerations in Z2/Z3. On the meta level, if you are getting advice from outside sources, then that is going to make your stated beliefs line up less often.

Z5->C10) You don’t want to do a favor for someone who can’t repay that favor.

Z6->C11) If you are looking to avoid saying blameworthy statements that could get you ridiculed or exiled, the last person whose lead you want to follow is someone who is about to be exiled.

Z7/Z8/Z9->C12) The person no longer around won’t be helpful here either.

Case D:

Second, consider that academics are reluctant to cite papers that seem correct, and which influenced their own research, if those papers were not published in prestigious journals, and seem unlikely to be so published in the future. They’d rather cite a less relevant or influential paper in a more prestigious journal. This is true not only for strangers to the author, but also for close associates who have long known the author, and cited that author’s other papers published in prestigious journals. And this is true not just for citations, but also for awarding grants and jobs. As others will mainly rely on journal prestige to evaluate paper quality, that’s what academics want to use in public as well, regardless of what they privately know about quality.

This seems discordant. I notice I am confused. Certainly, if accurate, this describes an important and meaningful ‘Hansonian’ phenomenon. I have no reason to presume it isn’t accurate. But what does this have to do with expressing beliefs or expressing agreement?

I am not an academic and have published zero academic papers, applied for zero grants of any kind, and sought zero academic jobs, so my model here could be quite inaccurate, but I do not see citations as mainly expressing agreement or belief.

I see citations as two things.

Citations are a way to assign prestige, and to associate with the prestigious, and otherwise play a political game. You and your paper are seen as more prestigious when they cite prestigious papers and others and/or are cited by others, especially other prestigious papers and authors. You and your paper are seen as less prestigious if the paper cites less prestigious things. These links also to some degree represent political alliances.

Citations also have mundane utility, allowing others to check and verify your sources, or find other information of interest. Such citations are helpful or outright required (e.g. “citation needed”) in order to make some claims, or to avoid charges of plagiarism.

This model would claim that the observation that people prefer to cite things from prestigious journals, rather than cite important papers or those of close associates, is an observation about how prestige is measured in the relevant places and for the relevant purposes. The claim becomes: People are measuring and awarding associative prestige mostly via journal inclusion.

For awarding grants or jobs, this is similarly claiming that such decisions are dominated by the prestige of one’s associated journals, including one’s indirectly associated journals, rather than via other considerations.

Again, I don’t know the extent to which this is true. Certainly it seems like a poor decision algorithm with little to recommend it, other than potentially being an inadequate equilibrium where deviations from it are punished. It still does not seem to me to be relevant to the question under discussion.

This story seems mostly to be about Goodhart’s Law. Others are using statistical analysis to evaluate you and your work, so you choose entries into that analysis that will make you score highly. Since you expect others to evaluate others based on such scores, you would also be wise to evaluate others and associate with them based on such scores, and on their willingness to evaluate others on that basis, and so on. No one here meaningfully believes any of it, or even says they believe any of it. Nor do people, when asked, judge the importance of a given paper in this way - they just won’t cite it if it would hurt their statistics.

Perhaps the theory here is that we will be more respected if we are seen agreeing with key audiences, and key audiences here are the prestigious journals? That the journals decide what to accept largely based on whether one regularly cites those prestigious journals? That does not seem right, but even if true and central, it does not seem like one is saying beliefs here, so much as paying off the powerful or playing a hierarchical role in a status game, or something like that.

Case E:

Third, consider the fact that most people will not accept a claim on topic area X that conflicts with what MSM (mainstream media) says about X. But that could be because they consider the media more informed than other random sources, right? However, they will also not accept this claim on X when made by an expert in X. But couldn’t that be because they are not sure how to judge who is an expert on X? Well let’s consider experts in Y, a related but different topic area from X. Experts in Y should know pretty well how to tell who is an expert in X, and know roughly how much experts can be trusted in general in areas X and Y.

The central claim offered for explanation is that most people will not accept claims about topic area X that conflict with what the MSM says about X, and that they choose to believe MSM over an “expert” in X.

After that, we consider the question of whether we can reliably know who is an expert in X, and it is suggested that one’s expertise in Y should allow identification of experts in X.

This last claim confuses me, and mostly seems wrong. Why should an expert in Y know better how to judge who is an expert in X? What is the relationship between X and Y, or between experts in different areas? To what extent is there a generic ‘identify expert’ skill that one gets from being an expert in something? Many people are an expert in some Y, however narrow or obscure, and most neither seem to find this useful in evaluating who is an expert in X, nor in realizing that the MSM are doubtless getting Y wrong, often on the level of ‘wet ground causes rain,’ and thus the MSM’s view of X is likely similarly wrong.

If you haven’t done so, think about the Ys that you know best, and ask how well the MSM’s views on those match the reality you know. Then assume their view on a given X is likely to be similar.

I would also pause to question the claim that most people mostly do not abide claims in conflict with MSM. That seems wrong to me, especially now in 2020. There is a class of such folks, but they seem to be a minority. Certainly they are not a majority of the red tribe, where it is common to fail to accept the election results, or to believe in QAnon.

In the blue tribe, from what I can tell, the new hotness is to claim that “the experts” claim X rather than that MSM claims X. The media is mostly seen as one way to identify such experts, but local social media narrative is considered another, and many local groups have very distinct sources of such expertise and for evaluating expertise claims.

Here’s one that crosses tribal lines, and for which the MSM definitely does not endorse: Almost half of Americans think Jeffery Epstein was murdered.

Or, in a world in which the Blue Tribe and Red Tribe usually have very different beliefs about what is being reported on today’s news, and there is a Blue Tribe subset who believes a third set of things, and a Grey Tribe that believes a fourth set of things, and so on, in what way can it be said that most people only accept the claims of the mainstream media?

While I dispute the claim about MSM, I do think citing MSM here is distracting from the intended central point. What matters is not what MSM says, what matters is that any given local group usually has something that is locally trusted to be the source of expertise and knowledge and that therefore serves the old purpose of the MSM. It does not matter that this is usually, or at least often, no longer the MSM itself. Alternatively, we could go back in time to a time when the MSM claim was mostly true, since the relevant drivers of human behavior likely have not changed.

One could say that any given local group is (usually) going to have some recognized source of common knowledge. When an “expert” in N says something about N, most people will reject this if it differs from the local common knowledge source’s statements about N, unless one expects the statements from the local common knowledge source to change, perhaps because of the expert’s statements.

That much I would agree with, so now the question becomes why.

Once again, we can look at categories of explanation X, Y and Z. Category X suggests that you doubt the reliability of the information. Category Y suggests you might not want to believe the statement even if true. Category Z suggests you might not want to say you believe the statement, even if you did believe it and/or it was true.

In terms of truth value, there are several challenges that seem relevant.

First, there’s the question of whether or not, and in what sense, this person claiming to be an “expert” is in fact an “expert.” People lie about being an expert. People are mistaken about being an expert. People can become an “expert” without being an expert, by getting appropriate reputation or credentials without knowledge, even of what other “experts” believe.

Robin’s response is that an expert on Y should be able to evaluate claims of expertise in X. Which, still, I fail to understand. I consider myself an expert on several things, but I do not consider myself that good at identifying experts in fields for which I am not an expert. I am not even confident I know what the word expert is supposed to mean, here or in another context. Certainly I can look at credentials, but that isn’t even a function of my being an expert in anything, nor do I think it is all that meaningful.

Second, there’s the question of whether the “experts,” in general, are a good source of truth. There are a number of reasons to doubt this. As Robin would presumably agree, experts will be motivated largely to say things that raise the status of experts in general, experts in their field or themselves in particular, or otherwise serve their purposes. Thus, an expert would be expected to express unjustified confidence. An expert would be expected to be dismissive of non-expert sources of information. An expert would tend to say things and reach conclusions that generate the need for more experts and expertise, and that make them seem more prestigious and important, or get them paid more.

When we talk about “experts”, usually we are talking about those who went through certain systems and obtained certain credentials. Why should you assume that this determines knowledge, let alone that you can expect transmission of this knowledge to you?

Experts always come with systematic biases, as those who chose to study a thing are not a random sample. Bible experts tell you that it is important to study the bible. Geologists will tell you that it is important to study rocks. An expert DJ will tell you of the centrality of a good party. Should you update on any of those statements?

In my weekly Covid-19 posts, I have continuously pointed out places in which I believe the “experts” are deviating from the truth, in ways likely to cost many lives and much happiness and prosperity, and explored many of the dynamics involved. If there’s a group that has taken an even bigger hit to their level of trust than the MSM, it might be “experts.”

Even if we conclude that experts in general know things, and that a given person counts as one of those experts, and that this person is doing their best to inform us of their true beliefs, that’s still not enough.

Suppose four out of five dentists recommend one brand of toothpaste. One in five recommends the other. Let us assume all their motives are pure. It would not be difficult for the less recommended brand to find a dentist to recommend their brand to us.

If the MSM consensus is that brand X is better than brand Y, and we encounter an expert claiming the superiority of brand Y, we should be suspicious that this message was brought to us by brand Y, even if the expert does believe in brand Y. Even if we asked one expert at random, we should still worry that there is some reason MSM still endorses X over Y, and suspect we got an unusual expert.

The experts who talk the loudest to us are often being loud because others disagree or the consensus is against them, another reason to doubt them. Or we hear them because they are optimizing for messages people want to hear or will reward them for or will generate clicks, or whatnot, and none of that seems reliable either.

I am strongly opposed, in general, to modesty arguments that say that one should not think for one’s self or try to figure things out, or if one does that one should only average that view in with those of many others, because others have already done so and you are not smarter than the collective intelligence of those others.

I am also strongly opposed, however, to the decision algorithm that says one should categorize people as “experts” or “non-experts” and then believe whatever an “expert” tells you without using your own non-expert judgment to evaluate such claims.

In general, if those are our only choices, in context the modesty argument seems strong. The local common knowledge algorithm presumably considers expert opinion in general, so why should you take the word of one expert over that consensus?

One reason would be if the expert credibly claims to have new information or new arguments. Thus, the expected future consensus will agree with the expert. If you believe this, it makes sense to get out in front of it.

A related reason would be if the expert credibly claims to have expert knowledge of future consensus as their new information. Given all you are doing is believing consensus anyway, it makes sense to believe the future consensus over past consensus, if the claim is credible.

An alternative reason would be that the expert is offering detailed info and claims that are beyond the scope of the information processing ability of the consensus. The consensus is absorbing a simplified message, and this is the detailed and actually correct message. Which is a good reason, but mostly the new detailed info should not contradict the consensus message, but rather expand upon it. And most people seem fine with such expanded explanations. In cases where the expert is claiming there are common misconceptions or errors due to the simplification process or other distortions, you could consider that too.

The best case would generally be if you actually evaluate the claims involved, which in general is the method I prefer, but that’s a very different case.

It does not seem like a good algorithm, even for pure truth extraction, to say that when you see a single expert on X disagree with MSM or local consensus on X, you should mostly believe the expert and disbelieve MSM or local consensus, unless it is an appeal that there is a greater authority that is more trustworthy but not as often checked, or something similar, and anticipates future local consensus if one cared enough to update people.

A more reasonable algorithm would be to say that if you found the foremost expert on X, or a consensus of experts on X, you should prefer that to the MSM or local consensus.

So again, I find the truth-seeking explanations compatible with and sufficient for, in practice, mostly not believing any given person coming along claiming (even plausibly) to be an expert, when they say things that contradict local consensus. Whereas it does not seem like a safe or viable strategy to do the opposite.

We might summarize as something like:

E1) “Expert” may not be an expert. We often can’t well pr cheaply evaluate this.

E2) “Expert” may refer to credentials rather than expertise.

E3) Expert may not reflect expert consensus, and often is actively selected for this. The presence of this expert could be the result of hostile action.

E4) The expert may be giving us this info because it helps them or experts.

E5) The expert may be lying or mistaken. Expert credibility in general is not high.

E6) Consensus likely already reflects expert’s information. Modesty arguments.

E7) Consensus likely to be missing detailed info, but why is it contradicting info?

That does not mean that such arguments are driving most refusals to listen to experts. It may be, or it may not be.

I do think it is a major factor. In particular, I think that the step “conclude that a person is an expert who we can trust on this in various senses” is highly relevant and suspect most of the time, even if one’s only target is the accuracy of one’s map.

Thus, there seem to be many good and important X-reasons for such behaviors.

Other factors are big too! We now get into all the Y-reasons and Z-reasons on the list.

I won’t go over each of them one by one a second time here, but I did check and yes each of them applies. There are good (as in useful) reasons not to act as if one believes different things than those around you or their expected future (expressed) beliefs. There are similarly good reasons not to say one believes different things than those around you are expected to express.

In a situation in which the X-concerns can be overcome and become reasons to accept new info rather than reject it, leaving only Y-concerns and Z-concerns, it is unclear how most people would then weigh such concerns in various situations, if one did not expect others to become convinced. In general, I agree with Robin’s model that most people will reject or at least not claim to believe most new info that violates consensus and that they do not expect to become consensus, because most info’s truth value is not important to most folks.

Time to move on to Robin’s conclusion:

These examples suggest that, for most people, the beliefs that they are willing to endorse depend more on what they expect their key audiences to endorse, relative to their private info on belief accuracy. I see two noteworthy implications.

Although I don’t think the case in question was proven by the examples, a strong endorsement of the central concept of “people mostly say things because they think key audiences around them will say they agree” or more precisely, “most people’s willingness to say they believe X has more to do with their anticipation of matching what they expect key others to say about X, than on their model of the truth value of X.”

But worth noting that this conclusion seems more general, and less specifically about respect from key audiences in particular.

Then his takeaways from this, starting with the first one:

First, it is not enough to learn something, and tell the world about it, to get the world to believe it. Not even if you can offer clear and solid evidence, and explain it so well that a child could understand. You need to instead convince each person in your audience that the other people who they see as their key audiences will soon be willing to endorse what you have learned. So you have to find a way to gain the endorsement of some existing body of experts that your key audiences expect each other to accept as relevant experts. Or you have to create a new body of experts with this feature (such as say a prediction market). Not at all easy.

The takeaway here is hard to fully interpret, but seems far too strong and general.

Certainly one does not need to convince each person in your audience, for if you convinced enough people then the others would presumably notice and follow suit, rendering the first group correct. Often the necessary group to start this information cascade is quite small. If people believe that “X is true” is actually mostly a claim that says “I expect soon for key people to be saying X is true” then a sufficiently reliable (in ways relevant to the cascade) single person should be able to often begin this process without offering any evidence for X.

Similarly, the endorsement of some body of experts is one potential way to cause this cascade, but most changes in expressed belief happen without such a body of experts. Perhaps this would be the best way in which one could generate a formal process for reliably getting people to endorse some new X, but there are lots of other ways too.

Nor do I see how the examples offered much differentiate between the hypothesis “child level explanation and proof” versus “expected social proof.” It also hides the question of how people expect those key people to decide what to endorse. Especially the question of, if you can provide a simple and clear proof, when would that be expected to cause the necessary changes, versus when it would not cause those changes. Yes, we can say that people will potentially be reluctant to endorse the new information unless they expect key others to later endorse it, but we need to know why those others would later be reluctant, or not be reluctant, and so on.

This seems to also include the claim that any given new info invokes this worry about not endorsing things key others will not soon endorse. I do not think that is the case, and certainly the case was not made here. There are claims where one must be careful not to disagree with such key people, and other claims where this is much less of a concern or not at all a concern. There are also other concerns that sometimes matter less or more.

Now the second:

Second, you can use these patterns to see which of your associates think for themselves, versus aping what they think their audiences will endorse. Just tell them about one of the many areas where experts in X disagree with MSM stories on X (assuming their main audience is not experts in X). Or see if they will cite a quality never-to-be-prestigiously-published paper. Or see if they will seek out the advice of a soon-to-be-retired manager. See not only if they will admit to which is more accurate in private, but if they will say when their key audience is listening.

The second conclusion is making an interesting claim, that such patterns both have been expressed in the examples, and can be used to determine who thinks for themselves versus aping what they think their audience will endorse. That seems different from wanting true beliefs versus wanting consensus beliefs, or wanting to claim true beliefs versus wanting to claim consensus beliefs.

If someone seeks out the advice of a soon-to-be-retired manager, that presumably means they wanted the information that person can provide, and were willing to pay the opportunity cost to get it. As noted above, there are good reasons to not think such info is as valuable. Even if one is thinking for oneself, there are plenty of good reasons to prefer seeking the advice of a not-retiring manager. If you made it very cheap to get such info, and such a manager still seemed like a good source of info, and they still chose to seek out someone else, then that’s evidence. But it’s not all that strong. Even if one thinks for one’s self, learning what the consensus is, or forming alliances and debts and connections, or other such motives, all will still matter to you. And it’s common, or at least certainly possible, for someone to think for themselves, yet do their best to ape their audience’s expectations in many key situations. Many free thinkers keep their heresies at least partly to themselves.

On the question of expert consensus (note the change from individual expert to consensus here), I strongly disagree that this is a good test even if they fully believe you. I have gotten strong pushback from definitely not free-thinking people who cite “expert consensus” about something as the overriding consideration, and threaten to exile or shame or otherwise punish those who defy it. Whereas I know plenty of definitely free-thinking people who think that ‘expert consensus’ is not to be trusted, although most would trust it in most cases over the MSM opinion if those were the only choices, since the MSM opinion would mostly be trusted even less. I’d think of this as, there are two authorities, and you’re telling people that they should listen to one authority rather than another, and judging those who do this ‘free thinkers.’ That doesn’t seem right. A free thinker wouldn’t blindly accept anyone’s claims.

I might be getting distracted here by ‘think for themselves’ rather than ‘be willing to express disagreement with those around you who can punish you for it.’ In which case, you could argue that MSM is going to be what most believe, and so willingness to go against this is strong evidence. Maybe. In my experience, if there is a clear expert consensus, then you can say that, and many people will contextually flat out believe you.

On citations, I continue not to get this as a way to differentiate. Citing a quality but not-prestigious paper is evidence that this person values actually conveying information and creating clarity, and values justice by rewarding the high-quality paper, more than the person values pumping up their own statistics in the system. Which is great, but doesn’t seem like it is a good proxy for ‘think for yourself.’ I suppose it does do a good job of asking whether you can know if the person is only maximizing for their statistical results, but it still seems like quite the odd test.

The final suggestion is to differentiate both what is said in private, and what is said when key audiences are listening. There are several possible people here, not only the extremes. There are those who effectively mostly believe what they think others want them to say they believe (full Y therefore also Z). There are those who optimize their maps for accuracy and then state their true beliefs (full X). Neither is ever fully extreme, but it can get close. Then there are those in between, who will espouse appropriate beliefs when necessary, but still are doing at least some work to optimize for map accuracy. They will balance, and choose under what circumstances to reveal their true beliefs or not, and also balance which beliefs are worth going along with to make things easier versus rejecting because they do too much damage to map accuracy.

What you are in the dark seems like the thing to be most interested in most of the time. Whether or not someone is thinking for themselves and attempting to improve maps when given a free or at least cheap opportunity.

We also of course need to be interested in how strong an incentive will get this person to stop creating clarity and start doing other things instead. There are huge gains to be had when people are willing to make that bar as ludicrously high as possible, and let the chips fall where they may. Where they are working to be aware of and willing to continuously point out when they are doing something else instead, while acknowledging that no one will ever stop doing such things entirely, nor would it be strategically wise to entirely do so.

The big distinction in my model, most of the time, is between those who aim to create clarity versus destroy it when given the choice, or in which if any circumstances someone is willing to do this, rather than looking for those willing to pay a maximal price to do so.

Or alternatively, I’d like to find someone who has beliefs about the physical world at all, especially if they’re willing to openly discuss at least some of them under at least some circumstances. Getting them to openly state them all the time is a big ask.

Especially since I definitely don’t uphold these extreme versions myself!

Finally:

And I’m sure there must be more examples that can be turned into tests (what are they?).

Most definitely.

There are several things we might want to test. We want to know who is trying to build an accurate map. We also want to know who would tell you the contents of their map, versus what they think you want to hear or would otherwise be strategically useful, or (often more accurately) following systems that instinctively tell them what seems like the thing to say based on the vibes they are getting rather than pursuing a goal.

Creating hard and fast rules, especially that differentiate between intermediate strategies, seems difficult. There is also the issue that we do not know who one might be trying to please with one’s statements or actions, or what might please such people. In some cases, what looks like being open minded is not that at all, but rather choosing an unexpected target one is trying to please, or actively trying to upset.

Take religion. The presumption would be that someone thinking for themselves would consider various religions, as well as atheism and agnosticism. If one’s religion matches that of those around them, or their parents, or they adopt the religion of a significant other, or otherwise match or move to match in such ways, it seems likely that this is due to mimicry. Whereas if someone selects something locally rare, that presumably is the opposite. We could also look at the questions such people ask. If one is wondering what those around them say and do, that seems like mimicry. If one is trying to figure out logic and accuracy, that seems like something else.

Yet other problems exist. If you change to another religion and move away, it could easily be because there was something to gain, rather than because you sought truth. Perhaps you wanted to make connections, or there was someone you liked (e.g. the significant other scenario), or perhaps you wanted to piss off the right people. Or perhaps you saw this new religion as something successful people believed, or thought it had higher status, or something. Or its statues looked cool, or any number of other reasons.

Pretty much any example is going to have similar murkiness. Suppose one looks at buying a car. If people wanted to buy the best cars, you would mostly hear car advertisements talk about why their cars were better. If people wanted to buy the cars that others were buying, or that would raise others’ opinion of them when they saw those cars, or that would match the impression others had of us, we would see car advertisements about emotional associations and popularity (best selling in class), plus some appeal to authority (Motortrend car of the year and so on), which is what we do see. Even when we do see facts, we usually see them selected to point out ways in which a given car is better than the more popular similar car, which again shows where everyone’s head is at.

When looking at someone’s car purchase, and the research that goes into it, it seems fair to ask whether they cared about what signified what and what was popular, and what other people would think about the purchase, or whether they cared about the technical details of the car and whether it would work. If you are paying attention, it is easy to tell the difference.

One can ask the same question about other purchases, such as phones. Or other big decisions, like what career to pursue, what college if any to attend and what major to choose, or who to date and perhaps marry, or what political views to adopt. And one can look at the messages various sources are looking to send about such decisions, to see which aspect of such choices is being sold to you.

And so on. One can look at final decisions, but more useful when possible is to look carefully for methodology behind those decisions, including both expressed and effective methodology.

What we cannot do is to treat any pursuit of information about what others would prefer you to claim to believe, as too strong a piece of evidence that you are not concerned with truth or thinking for yourself. Knowing what others expect is valuable information, as it allows you to predict reactions of others and model what they might say or do, and allow one to decide with whom to associate and what moves to attempt. How people react to others is central to one’s model of the world, if one is to have a useful model. In general, any information that would be useful to a mimic is also useful to an inquirer.

What I do think we can infer from more reliably is the amount of specific truth-gathering. Talking to the non-retiring advisor tells us little. Talking to the retiring advisor tells us a lot more.