Back in November 2024, Scott Alexander asked: Do longer prison sentences reduce crime?

As a marker, before I began reading the post, I put down here: Yes. The claims that locking people up for longer periods after they are caught doing [X] does not reduce the amount of [X] that gets done, for multiple overdetermined reasons, is presumably rather Obvious Nonsense until strong evidence is provided otherwise.

The potential exception, the reason it might not be Obvious Nonsense, would be if our prisons were so terrible that they net greatly increase the criminality and number of crimes of prisoners once they get out, in a way that grows with the length of the sentence. And that this dwarfs all other effects. This is indeed what Roodman (Scott’s anti-incarceration advocate) claims. Which makes him mostly unique, with the other anti-incarceration advocates being a lot less reasonable.

In which case, yes, we should make dramatic changes to fix that, rather than arguing over sentence lengths, or otherwise act strategically (e.g. either lock people up for life, or barely lock them up at all, and never do anything in between?) But the response shouldn’t be to primarily say ‘well I guess we should stop locking people up then.’

Scott Alexander is of course the person we charge with systematically going through various studies and trying to draw conclusions in these spots. So here we are.

Deterrence

First up is the deterrence effect.

Scott Alexander: Rational actors consider the costs and benefits of a strategy before acting. In general, this model has been successfully applied to the decision to commit crime. Studying deterrence is complicated, and usually tries to tease out effects from the certainty, swiftness, and severity of punishment; here we’ll focus on severity.

According to every study and analysis I’ve seen, certainty and swiftness matter a lot, and indeed you get more bang for your buck on those than you do on severity past some reasonable point. The question on severity is if we’re reaching decreasing marginal returns.

A bunch of analysis mostly boils down to this:

I think all four of these studies are consistent with an extra year tacked on to a prison sentence deterring crime by about 1%. All studies start with significant prison sentences, and don’t let us conclude that the same would be true with eg increasing a one day sentence to a year-and-a-day.

Helland and Drago et al both suggest that deterrence effects are concentrated upon the least severe crimes. I think this makes sense, since more severe crimes tend to be more driven by emotion or necessity.

I would have predicted a larger effect than this, but it’s not impossible that once you’re already putting someone away for 5+ years you’ve already done most of the deterrence work you’re going to do via sentence length alone - if you thought you’d be caught and cared about your future you wouldn’t be doing it.

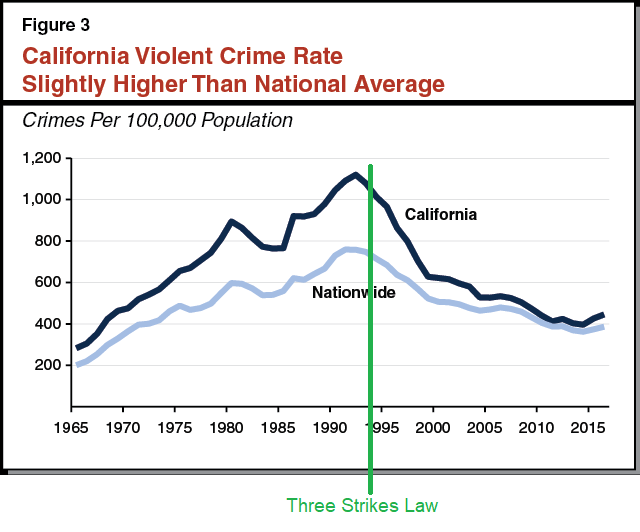

The incarceration effects, on the other hand, naively look rather huge. There’s strong evidence that a few people will constantly go around committing all the crime. If you lock up those doing all the crime, they stop doing the crime, and crime goes down. The math is clear. So why didn’t California’s three strikes law do more work?

If you credit three strikes with the change in relative crime for five years after the law was passed, you get a 7% drop, although ‘most criminologists suggest that even this is an overestimate, and the true number is close to zero.’

I actually think the 7% estimate looks low here. We see a general trend beforehand of California’s crime rate spiralling out of control, both in absolute and relative terms. It seems likely this trend had to be stalled before it was reversed, and the gap was essentially gone after a while, and other states were also going ‘tough on crime’ during that period, so the baseline isn’t zero.

So we expected Three Strikes to decrease crime by 83%, but in fact it decreased it by 0-7%. Why?

Because California’s Three Strikes law was weaker than it sounds: it only applied to a small fraction of criminals with three convictions. Only a few of the most severe crimes (eg armed robberies) were considered “strikes”, and even then, there was a lot of leeway for lenient judges and prosecutors to downgrade charges. Even though ~80% of criminals had been arrested three times or more, only 1-4% of criminals arrested in California were punished under the Three Strikes law.

Whereas a Netherlands 10-strike (!) law, allowing for much longer sentences after that, did reduce property crime by 25%, and seems like it was highly efficient. This makes a lot of sense to me and also seems highly justified. At some point, if you’re constantly doing all the crime, including property crime, you have to drop the hammer.

We are often well past that point. As Scott talks about, and this post talks about elsewhere (this was the last section written), the ‘we can’t arrest the 327 shoplifters in NYC who get arrested 20 times per year’ is indeed ‘we suck.’ This isn’t hard. And yes, you can say there’s disconnects where DAs say an arrest is deterrent enough whereas police don’t see a point to arresting someone who will only get released, but that doesn’t explain why we have to keep arresting the same people.

Analyses from all perspectives, that Scott looks at, agree that criminals as a group tend to commit quite a lot of crime, 7-17 crimes per year.

I also note that I think all the social cost estimates are probably way too low, because they aren’t properly taking into account various equilibrium effects.

El Salvador

That’s what I think happened in El Salvador, that Scott is strangely missing. The reason you got a 95% crime decrease is not some statistical result based on starting with lower incarceration rates. It is because before the arrests, the gangs were running wild, were de facto governments fighting wars while the police were powerless. Afterwards, they weren’t. It wasn’t about thinking on the margin.

We also get confirmation that theft is way down in El Salvador, in a ‘now I can have a phone in my hand or car on the street and not expect them to be stolen so often I can’t do that’ sense.

Roodman on Social Costs of Crime

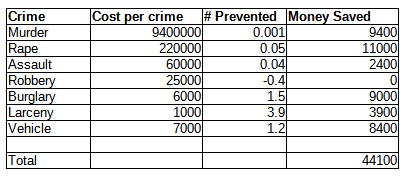

Later on, Roodman attempts to estimate social costs like this:

Roodman uses two methods: first, he values a crime at the average damages that courts award to victims, including emotional damages. Second, he values it at what people will pay - how much money would you accept to get assaulted one extra time in your life?

These estimates still exclude some intangible costs, like the cost of living in a crime-ridden community, but it’s the best we can do for now.

These to me seem like they are both vast underestimates. I don’t think we can just say ‘best we can do’ and dismiss the community costs.

I would pay a lot to not be assaulted one time. I’d pay so much more to both not be assaulted, and also not to have the fear of assault living rent free in my head all the time (and for women this has to be vastly worse than that). And for everyone around me to also not having that dominate their thinking and actions.

So yeah, I find these estimates here rather absurdly low. If we value a life at $12 million when calculating health care interventions, you’re telling me marginal murders only have a social cost of $9.4 million? That’s crazy, murder is considered much worse than other deaths and tends to happen to the young. I think you have to at least double the general life value.

The rape number is even crazier to me.

Here’s Claude (no, don’t trust this, but it’s a sanity check):

Claude Sonnet 3.5: Studies estimating the total societal cost per rape (including both tangible and intangible costs) typically range from $150,000 to $450,000 in direct costs. When including long-term impacts and psychological harm, some analyses place the full societal cost at over $1 million per incident.

…

Total cost estimates per burglary typically range from $3,000 to $7,000 in direct costs, with comprehensive social cost estimates ranging from $10,000-$25,000 per incident when including psychological impact and system costs.

So yeah, I think even without norm and equilibrium effects these numbers are likely off by a factor of at least 2, and then they’re wrong by a lot again for those reasons.

Scott later points out that thinking on the margin gets confusing when different areas have different margins, and in some sense the sum of the margins must be the total effect, but some sort of multiple equilibrium (toy) model seems closer to how I actually think about all this.

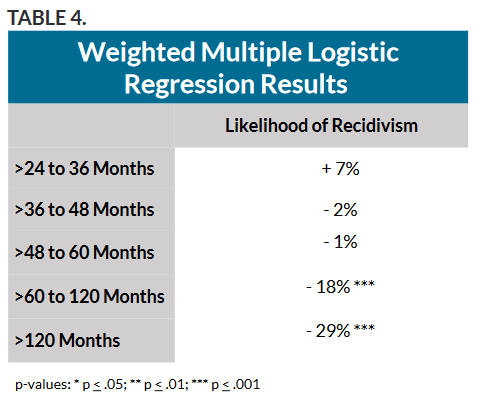

Recidivism

The aftereffects of imprisonment forcing or leading people deeper into crime is the actual counterargument. And as Scott points out, it’s crazy to try and claim that the impact here is zero:

As far as I can tell, most criminologists are confused on this point. They’re going to claim that the sign of aftereffects is around zero, or hard to measure - then triumphantly announce that they’ve proven prison doesn’t prevent crime.

If the effect here is around zero, one that’s quite the coincidence, and two that would mean prison reduces crime. The actual argument that prison doesn’t reduce crime, that isn’t Obvious Nonsense, is if the aftereffects are very large and very negative.

Here’s one study that definitely didn’t find that.

Scott then says there are tons of other studies and it’s all very complicated. There’s lots of weirdness throughout, such as Berger saying everyone pleading guilty means a ‘unusual study population’ despite essentially everyone pleading guilty in our system.

Roodman not only concludes that longer sentences increase crime after, but that harsher ones also do so, while saying that effects at different times and places differ.

Another suggestion is that perhaps modest sentences (e.g. less than two years) are more relatively disruptive versus incentivizing, and thus those in particular make things worse. That doesn’t seem impossible, but also the incentive effects on the margin here seem pretty huge. You need to be disruptive, or where is the punishment, and thus where is the deterrence? Unless we have a better idea?

Given the importance of both swiftness and certainty, a strategy of ‘we won’t do much to you until we really do quite a lot to you’ here would be even worse than the three strikes law.

I mean, I can think of punishments people want to avoid, but that aren’t prison and thus won’t cost you your job or family… but we’ve pretty much decided to take all of those off the table?

Note on Methodology

In general, I’ve taken to finding Scott’s ‘let’s look at all the studies’ approach to such questions to be increasingly not how I think about questions at all. Studies aren’t the primary way I look for or consider evidence. They’re one source among many, and emphasizing them this much seems like a cop out more than an attempt to determine what is happening.

Conclusions

I do agree broadly with Scott’s conclusions, of:

More incarceration net reduces crime.

We have more cost-effective crime reduction options available.

It would be cost effective to spend more on crime reduction.

To that I would add:

More incarceration seems net beneficial at current margins, here, because the estimates of social cost of (real, non-victimless) crime are unreasonably low even without equilibrium effects, and also there are large equilibrium effects.

We have additional even more effective options, but we keep not using them.

Some of that is ‘not ready for that conversation’ or misplaced ethical concerns.

Some of that is purely we’re bad at it.

We should beware medium-sized incarceration periods (e.g. 1-3 years).

Most importantly: Our current prison system is really bad in that many aspects cause more crime after release rather than less, and the low hanging fruit is fixing this so that it isn’t true.

At minimum, we absolutely should be funding the police and courts sufficiently to investigate crimes properly, arrest everyone who does crimes on the regular (while accepting that any given crime may not be caught), and to deal with all the resulting cases.

And of course we should adjust the list of crimes, and the punishments, to match that new reality. Otherwise, we are burning down accumulated social capital, and I fear we are doing it rather rapidly.

Highlights From Scott’s Comments

Scott then followed up with a highlights from the comments post.

It starts with comments about criminal psychology, which I found both fascinating and depressing. If prospective criminals don’t care about magnitude of risks only certainty of risk and they’re generally not competent to stay on the straight and narrow track and make it work, and they often don’t even see prison as worse than their lives anyway, you don’t have many options.

The obvious play is to invest bigly in ensuring you reliably catch people, and reduce sentences since the extra time isn’t doing much work, which is consistent with the conclusions above but seems very hard to implement at scale. Perhaps with AI we can move towards that world over time?

I very much appreciated Scott’s response to the first comment, which I’ll quote here:

Jude: This . . . matches my experience working with some low-income boys as a volunteer. It took me too long to realize how terrible they were at time-discounting and weighing risk. Where I was saying: "this will only hurt a LITTLE but that might RUIN your life," they heard: "this WILL hurt a little but that MIGHT ruin your life." And "will" beats "might" every time.

One frustrating kid I dealt with drove without a license (after losing it) several times and drove a little drunk occasionally, despite my warnings that he would get himself in a lot of trouble. He wasn't caught and proudly told me that I was wrong: nothing bad happened, whereas something bad definitely would have happened if he didn't get home after X party. Surprise surprise: two years later he's in jail after drunk driving and having multiple violations of driving without a license.

Scott Alexander: The “proudly told me that I was wrong - nothing bad happened” reminds me of the Generalized Anti-Caution Argument - “you said we should worry about AI, but then we invented a new generation of large language model, and nothing bad happened!” Sometimes I think the difference between smart people and dumb people is that dumb people make dumb mistakes in Near Mode, and smart people only make them in Far Mode - the smarter you are, the more abstract you go before making the same dumb mistake.

Yep. We need to figure out a better answer in these situations. What distinguishes situations where someone can understand ‘any given time you do this is probably net positive but it occasionally is massively terrible so don’t do it’ from ‘this was net positive several times so your warnings are stupid?’

There was some hopefulness, in this claim that the criminal class does still care about punishment magnitude, and about jail versus prison, as differing in kind - at some point the punishment goes from ‘no big deal’ to very much a big deal, and plea bargains reflect that. Which suggests you either want to enforce the law very consistently, or you want to occasionally go big enough to trigger the break points. But then the next comment says no, the criminals care so little they don’t even know what their punishments would be until they happen.

These could be different populations, or different interpretations, but mostly this seems like a direct contradiction. None of this is easy.

Something to keep in mind that makes a lot of these studies hard to detangle or apply common sense to is that different studies define recidivism differently, and it may also depart from an individual's common sense definition. It's similar to "assault weapons" in that way.

Typically if someone is convicted for robbery and is released on community supervision (probation, or parole after a prison sentence), they have additional rules to follow. Violation of those additional rules can lead to rearrest, reconviction, etc. This would generally be considered part of the recidivism metric. It does indicate a certain level of not-rule-following that is important to consider. However, it is not the same thing as being arrested for another robbery.

It would be nice to have a study that focused on reoffence, and even nicer to filter out various "victimless" crimes. I know dependency can create a vicious cycle but it would be interesting to see the difference in reoffence between robbery -> robbery / drugs -> drugs / drugs -> robbery / robbery -> drugs.

"Our current prison system is really bad in that many aspects cause more crime after release rather than less, and the low hanging fruit is fixing this so that it isn’t true."

"Hanging" seems to be the key word there.