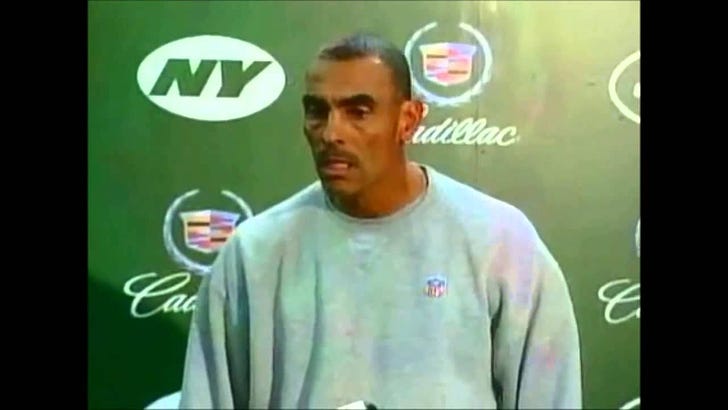

You Play to Win the Game

Previously (Putanumonit): Player of Games

Original Words of Wisdom.

Quite right, sir. Quite right.

By far the most important house rule I have for playing games is exactly that: You Play to Win the Game.

That doesn't mean you always have to take exactly the path that maximizes your probability of winning. Style points can be a thing. Experimentation can be a thing. But in the end, you play to win the game. If you don't think it matters, do as Herm Edwards implores us: Retire.

It's easy to forget, sometimes, what 'the game' actually is, in context.

The most common and important mistake is to maximize expected points or point differential, at the cost of win probability. Alpha Go brought us many innovations, but perhaps its most impressive is its willingness to sacrifice territory it doesn't need to minimize the chances that something will go wrong. Thus it often wins by the narrowest of point margins, but in ways that are very secure.

The larger-context version of this error is to maximize winning or points in the round rather than chance of winning the event.

In any context where points are added up over the course of an event, the game that matters is the entire event. You do play to win each round, to win each point, but strategically. You're there to hoist the trophy.

Thus, when we face a game theory experiment like Jacob faced in Player of Games, we have to understand that we'll face a variety of opponents with a variety of goals and methods. We'll play a prisoner's dilemma with them, or an iterated prisoner's dilemma, or a guess-the-average game.

To win, one must outscore every other player. Our goal is to win the game.

Unless or until it isn't. Jacob explicitly wasn't trying to win at least one of the games by scoring the most points, instead choosing to win the greater game of life itself, or at least a larger subgame. This became especially clear once winning was beyond his reach. At that point, the game becomes something odd - you're scoring points that don't matter. It's not much of a contest, and it doesn't teach you much about game theory or decision theory.

It teaches you other things about human nature, instead.

A key insight is what happens when a prize is offered for the most successful player of one-shot prisoner's dilemmas, or a series of iterated prisoner's dilemmas.

If you cooperate, you cannot win. Period. Someone else will defect while their opponents cooperate. Maybe they'll collude with their significant other. Maybe they'll lie convincingly. Maybe they'll bribe with out-of-game currency. Maybe they'll just get lucky and face several variations on 'cooperate bot'. Regardless of how legitimate you think those tactics are, with enough opponents, one of them will happen.

That means the only way to win is to defect and convince opponents to cooperate. Playing any other way means playing a different game.

When scoring points, make sure the points matter.

These issues will also be key to the next post as well, where we will analyze a trading board game proposed by Robin Hanson.