Scott Alexander famously warned us to Beware Trivial Inconveniences.

When you make a thing easy to do, people often do vastly more of it.

When you put up barriers, even highly solvable ones, people often do vastly less.

Let us take this seriously, and carefully choose what inconveniences to put where.

Let us also take seriously that when AI or other things reduce frictions, or change the relative severity of frictions, various things might break or require adjustment.

This applies to all system design, and especially to legal and regulatory questions.

Table of Contents

Insufficient Friction On Antisocial Behaviors Eventually Snowballs.

Principle #8: The Abundance Agenda and Deregulation as Category 1-ification.

Principle #10: Ensure Antisocial Activities Have Higher Friction.

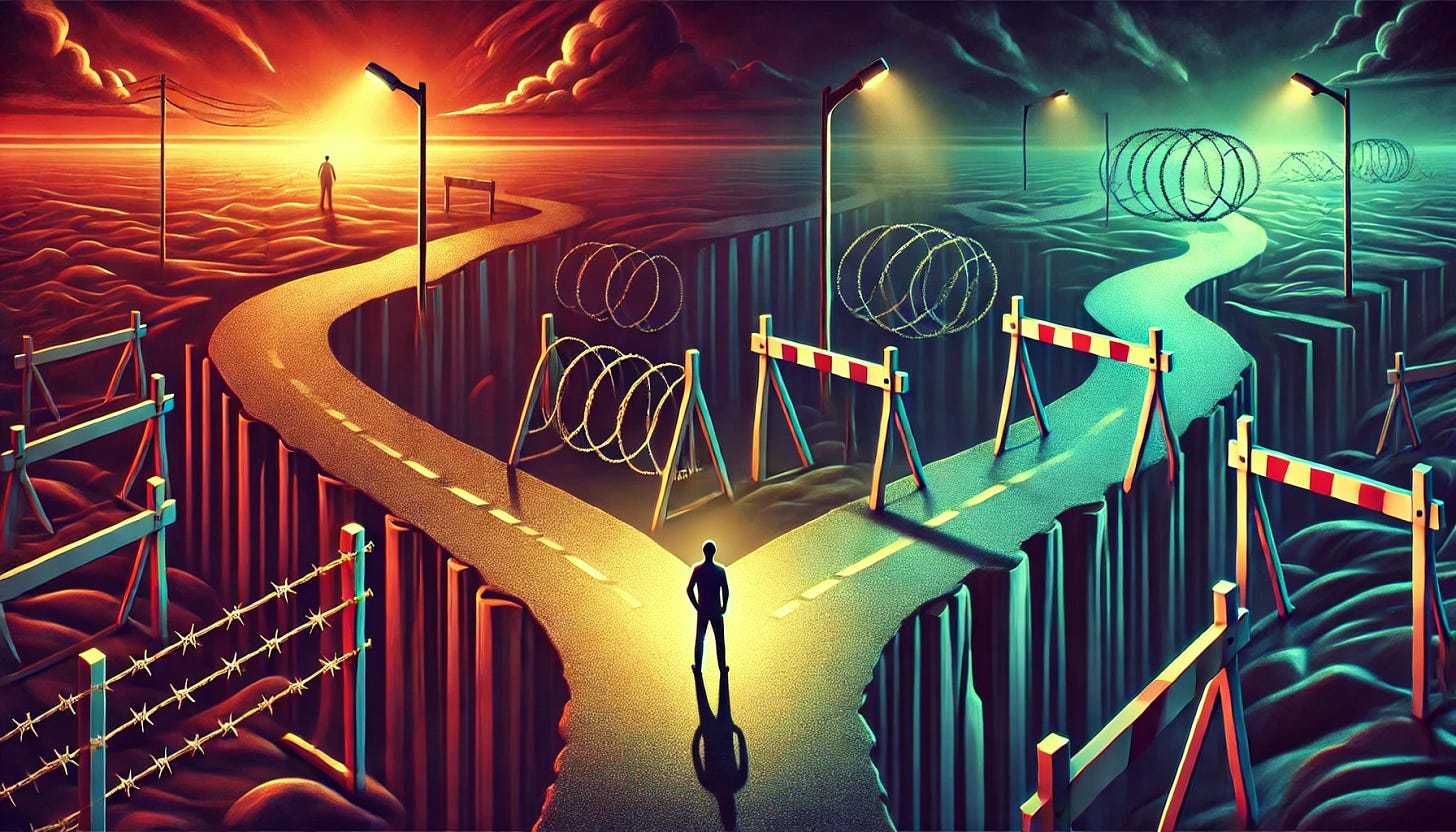

Levels of Friction (and Legality)

There is a vast difference along the continuum, both in legal status and in terms of other practical barriers, as you move between:

Automatic, a default, facilitated, required or heavily subsidized.

Legal, ubiquitous and advertised, with minimal frictions.

Available, mostly safe to get, but we make it annoying.

Actively illegal or tricky, perhaps risking actual legal trouble or big loss of status.

Actively illegal and we will try to stop you or ruin your life (e.g. rape, murder).

We will move the world to stop you (e.g. terrorism, nuclear weapons).

Physically impossible (e.g. perpetual motion, time travel, reading all my blog posts)

The most direct way to introduce or remove frictions is to change the law. This can take the form of prohibitions, regulations and requirements, or of taxes.

One can also alter social norms, deploy new technologies or business models or procedures, or change opportunity costs that facilitate or inhibit such activities.

Or one can directly change things like the defaults on popular software.

Often these interact in non-obvious ways.

It is ultimately a practical question. How easy is it to do? What happens if you try?

If the conditions move beyond annoying and become prohibitive, then you can move things that are nominally legal, such as building houses or letting your kids play outside or even having children at all, into category 3 or even 4.

Important Friction Principles

Here are 14 points that constitute important principles regarding friction:

By default more friction is bad and less friction is good.

Of course there are obvious exceptions (e.g. rape and murder, but not only that).

Activities imposing a cost on others or acting as a signal often rely on friction.

Moving such activities from (#2 or #1) to #0, or sometimes from #2 to #1, can break the incentives that maintain a system or equilibrium.

That does not have to be bad, but adjustments will likely be required.

The solution often involves intentionally introducing alternative frictions.

Insufficient friction on antisocial activities eventually snowballs.

Where friction is necessary, focus on ensuring it is minimally net destructive.

Lower friction choices have a big advantage in being selected.

Pay attention to relative friction, not only absolute friction.

Be very sparing when putting private consensual activities in #3 or especially #4.

This tends to work out extremely poorly and make things worse.

Large net negative externalities to non-participants changes this, of course.

Be intentional about what is in #0 versus #1 versus #2. Beware what norms and patterns this distinction might encourage.

Keep pro-social, useful and productive things in #0 or #1.

Do not let things that are orderly and legible thereby be dragged into #2 or worse, while rival things that are disorderly and illegible become relatively easier.

Keep anti-social, destructive and counterproductive things in at least #2, and at a higher level than pro-social, constructive and productive alternatives.

The ideal form of annoying, in the sense of #2, is often (but not always) a tax, as in increasing the cost, ideally in a way that the lost value is transfered, not lost.

Do not move anti-social things to #1 to be consistent or make a quick buck.

Changing the level of friction can change the activity in kind, not only degree.

When it comes to friction, consistency is frequently the hobgoblin of small minds.

It is a game of incentives. You can and should jury-rig it as needed to win.

Principle #1: By Default Friction is Bad

By default, you want most actions to have lower friction. You want to eliminate the paperwork and phone calls that waste time and fill us with dread, and cause things we ‘should’ do to go undone.

If AI can handle all the various stupid things for me, I would love that.

Principle #3: Friction Can Be Load Bearing

The problems come when frictions are load bearing. Here are five central causes.

An activity or the lack of an activity is anti-social and destructive. We would prefer it happen less, or not at all, or not expose people to it unless they seek it out first. We want quite a lot of friction standing in the way of things like rape, murder, theft, fraud, pollution, excessive noise, nuclear weapons and so on.

An activity that could be exploited, especially if done ruthlessly at scale. You might for example want to offer a promotional deal or a generous return policy. You might let anyone in the world send you an email or slide into your DMs.

An activity that sends a costly signal. A handwritten thank you note is valuable because it means you were thoughtful and spent the time. Spending four years in college proves you are the type of person who can spend those years.

An activity that imposes costs or allocates a scarce resource. The frictions act as a price, ensuring an efficient or at least reasonable allocation, and guards against people’s time and money being wasted. Literal prices are best, but charging one can be impractical or socially unacceptable, such as when applying for a job.

Removing the frictions from one alternative, when you continue to impose frictions on alternatives, is putting your finger on the scale. Neutrality does not always mean imposing minimal frictions. Sometimes you would want to reduce frictions on [X] only if you also could do so (or had done so) on [Y].

Insufficient Friction On Antisocial Behaviors Eventually Snowballs

Imposing friction to maintain good incentives or equilibria, either legally or otherwise, is often expensive. Once the crime or other violation already happened, imposing punishment costs time and money, and harms someone. Stopping people from doing things they want to do, and enforcing norms and laws, is often annoying and expensive and painful. In many cases it feels unfair, and there have been a lot of pushes to do this less.

You can often ‘get away with’ this kind of permissiveness for a longer time than I would have expected. People can be very slow to adjust and solve for the equilibrium.

But eventually, they do solve for it, norms and expectations and defaults adjust. Often this happens slowly, then quickly. Afterwards you are left with a new set of norms and expectations and defaults, often that becomes equally sticky.

There are a lot of laws and norms we really do not want people to break, or actions you don’t want people to take except under the right conditions. When you reduce the frictions involved in breaking them or doing them at the wrong times, there won’t be that big an instant adjustment, but you are spending down the associated social capital and mortgaging the future.

We are seeing a lot of the consequences of that now, in many places. And we are poised to see quite a lot more of it.

Principle #4: The Best Frictions Are Non-Destructive

Time lost is lost forever. Unpleasant phone calls do not make someone else’s life more pleasant. Whereas additional money spent then goes to someone else.

Generalize this. Whenever friction is necessary, either introduce it in the service of some necessary function, or use as non-destructive a transfer or cost as possible.

Principle #8: The Abundance Agenda and Deregulation as Category 1-ification

It’s time to build. It’s always time to build.

The problem is, you need permission to build.

The abundance agenda is largely about taking the pro-social legible actions that make us richer, and moving them back from Category 2 into Category 1 or sometimes 0.

It is not enough to make it possible. It needs to be easy. As easy as possible.

Building housing where people want to live needs to be at most Category 1.

Building green energy, and transmission lines, need to be at most Category 1.

Pharmaceutical drug development needs to be at most Category 1.

Having children needs to be at least Category 1, ideally Category 0.

Deployment of and extraction of utility from AI needs to remain Category 1, where it does not impose catastrophic or existential risks. Developing frontier models that might kill everyone needs to be at Category 2 with an option to move it to Category 3 or Category 4 on a dime if necessary, including gathering the data necessary to make that choice.

What matters is mostly moving into Category 1. Actively subsidizing into Category 0 is a nice-to-have, but in most cases unnecessary. We need only to remove the barriers to such activities, to make such activities free of unnecessary frictions and costs and delays. That’s it.

When you put things in category 1, magic happens. If that would be good magic, do it.

A lot of technological advances and innovations, including the ones that are currently blocked, are about taking something that was previously Category 2, and turning it into a Category 1. Making the possible easier is extremely valuable.

Principle #10: Ensure Antisocial Activities Have Higher Friction

We often need to beware and keep in Category 2 or higher actions that disrupt important norms and encourage disorder, that are primarily acts of predation, or that have important other negative externalities.

When the wrong thing is a little more annoying to do than the right thing, a lot more people will choose the right path, and vice versa. When you make the anti-social action easier than the pro-social action, when you reward those who bring disorder or wreck the commons and punish those who adhere to order and help the group, you go down a dark path.

This is also especially true when considering whether something will be a default, or otherwise impossible to ignore.

There is a huge difference between ‘you can get [X] if you seek it out’ versus ‘constantly seeing advertising for [X]’ or facing active media or peer pressure to participate in [X].

Sports Gambling as Motivating Example of Necessary 2-ness

Recently, America moved Sports Gambling from Category 2 to Category 1.

Suddenly, sports gambling was everywhere, on our billboards and in our sports media, including the game broadcasts and stadium experiences. Participation exploded.

We now have very strong evidence that this was a mistake.

That does not mean sports gambling should be seriously illegal. It only means that people can’t handle low-friction sports gambling apps being available on phones that get pushed in the media.

I very much don’t want it in Category 3, only to move it back to Category 2. Let people gamble at physical locations. Let those who want to use VPNs or actively subvert the rules have their fun too. It’s fine, but don’t make it too easy, or in people’s faces.

The same goes for a variety of other things, mostly either vices or things that impose negative externalities on others, that are fine in moderation with frictions attached.

The classic other vice examples count: Cigarettes, drugs and alcohol, prostitution, TikTok. Prohibition on such things always backfires, but you want to see less of them, in both the figurative and literal sense, than you would if you fully unleashed them. So we need to talk price, and exactly what level of friction is correct, keeping in mind that ‘technically legal versus illegal’ is not the critical distinction in practice.

On Principle #13: Law Abiding Citizen

There are those who will not, on principle, lie or break the law, or not break other norms. Every hero has a code. It would be good if we could return to a norm where this was how most people acted, rather than us all treating many laws as almost not being there and certain statements as not truth tracking - that being ‘nominally illegal with no enforcement’ or ‘requires telling a lie’ was already Category 2.

Unfortunately, we don’t live in that world, at least not anymore. Indeed, people are effectively forced to tell various lies to navigate for example the medical system, and technically break various laws. This is terrible, and we should work to reverse this, but mostly we need to be realistic.

Similarly, it would be good if we lived by the principle that you consider the costs you impose on others when deciding what to do, only imposing them when justified or with compensation, and we socially punished those who act otherwise. But increasingly we do not live in that world, either.

As AI and other technology removes many frictions, especially for those willing to have the AI lie on their behalf to exploit those systems at scale, this becomes a problem.

Mundane AI as 2-breaker and Friction Reducer

Current AI largely takes many tasks that were Category 2, and turns them into Category 1, or effectively makes them so easy as to be Category 0.

Academia and school break first because the friction ‘was the point’ most explicitly, and AI is especially good at related tasks. Note that breaking these equilibria and systems could be very good for actual education, but we must adapt.

Henry Shevlin: I generally position myself an AI optimist, but it's also increasingly clear to me that LLMs just break lots of our current institutions, and capabilities are increasing fast enough that it'll be very hard for them to adapt in the near-term.

Education (secondary and higher) is the big one, but also large aspects of academic publishing. More broadly, a lot of the knowledge-work economy seems basically unsustainable in an era of intelligence too cheap to meter.

Lawfare too cheap to meter.

Dick Bruere: I am optimistic that AI will break everything.

Then we get into places like lawsuits.

Filing or defending against a lawsuit is currently a Category 2 action in most situations. The whole process is expensive and annoying, and it’s far more expensive to do it with competent representation. The whole system is effectively designed with this in mind. If lawsuits fell down to Category 1 because AI facilitated all the filings, suddenly a lot more legal actions become viable.

The courts themselves plausibly break from the strain. A lot of dynamics throughout society shift, as threats to file become credible, and legal considerations that exist on paper but not in practice - and often make very little sense in practice - suddenly exist in practice. New strategies for lawfare, for engineering the ability to sue, come into play.

Yes, the defense also moves towards Category 1 via AI, and this will help mitigate, but for many reasons this is a highly incomplete solution. The system will have to change.

Job applications are another example. It used to be annoying to apply to jobs, to the extent that most people applied to vastly fewer jobs than was wise. As a result, one could reasonably advertise or list a job and consider the applications that came in.

In software, this is essentially no longer true - AI-assisted applications flood the zone. If you apply via a public portal, you will get nowhere. You can only meaningfully apply via methods that find new ways to apply friction. That problem will gradually (or rapidly) spread to other industries and jobs.

There are lots of formal systems that offer transfers of wealth, in exchange for humans undergoing friction and directing attention. This can be (an incomplete list):

Price discrimination. You offer discounts to those willing to figure out how to get them, charge more to those who pay no attention and don’t care.

Advertising for yourself. Offer free samples, get people to try new products.

Advertising for others. As in, a way to sell you on watching advertising.

Relationship building. Initial offers of 0% interest get you to sign up for a credit card. You give your email to get into a rewards program with special offers.

Customer service. If you are coming in to ask for an exchange or refund, that is annoying enough to do that it is mostly safe to assume your request is legit.

Costly signaling. Only those who truly need or would benefit would endure what you made them do to qualify. School and job applications fall into this.

Habit formation. Daily login rewards and other forms of gamification are ubiquitous in mobile apps and other places.

Security through obscurity. There is a loophole in the system, but not many people know about it, and figuring it out takes skill.

Enemy action. It is far too expensive to fully defend yourself against a sufficiently determined fraudster or thief, or someone determined to destroy your reputation, or worse an assassin or other physical attacker. Better to impose enough friction they don’t bother.

Blackmail. It is relatively easy to impose large costs on someone else, or credibly threaten to do so, to try and extract resources from them. This applies on essentially all levels. Or of course someone might actually want to inflict massive damage (including catastrophic harms, cyberattacks, CBRN risks, etc).

Breaking all these systems, and the ways we ensure that they don’t get exploited at scale, upends quite a lot of things that no longer make sense.

In some cases, that is good. In others, not so good. Most will require adjustment.

Future more capable AI may then threaten to bring things in categories #3, #4 and #5 into the realm of super doable, or even start doing them on its own. Maybe even some things we think are in #6. In some cases this will be good because the frictions were due to physical limitations or worries that no longer apply. In other cases, this would represent a crisis.

What To Do About All This

To the extent you have control over levels of friction of various activities, for yourself or others, choose intentionally, especially in relative terms. All of this applies on a variety of scales.

Focus on reducing frictions you benefit from reducing, and assume this matters more than you think because it will change the composition of your decisions quite a lot.

Often this means it is well worth it to spend [X] in advance to prevent [Y] amount of friction over time, even if X>Y, or even X>>Y.

Where lower friction would make you worse off, perhaps because you would then make worse choices, consider introducing new frictions, up to and including commitment devices and actively taking away optionality that is not to your benefit.

Beware those who try to turn the scale into a boolean. It is totally valid to be fine with letting people do something if and only if it is sufficiently annoying for them to do it - you’re not a hypocrite to draw that distinction.

You’re also allowed to say, essentially ‘if we can’t put this into [1] without it being in [0] then it needs to be in [2] or even ‘if there’s no way to put this into [2] without putting it into [1] then we need to put it in [3].’

You are especially allowed to point out ‘putting [X] in [1 or 0] has severe negative consequences, and doing [Y] makes puts [X] there, so until you figure out a solution you cannot do [Y].’

Most importantly, pay attention to all this especially as yourself and other people will actually respond, take it seriously, and consider the incentives, equilibria, dynamics and consequences that result, and then respond deliberatively.

Finally, when you notice that friction levels are changing, watch for necessary adjustments, and to see what if anything will break, what habits must be avoided. And also, of course, what new opportunities this opens up.

It is interesting that despite freedom of religion, even highly spiritual people often don't pray regularly, despite no formal barriers. The obstacle is friction: the simple need to redirect attention.

Social friction once regulated behavior effectively, but modern norms have weakened this mechanism. This makes social enforcement nearly impossible. For example, while it's still socially acceptable to mock someone for being a prude, it's politically unviable to look down on someone for, say, engaging in promiscuous behavior.

Consider business ethics: The Bible's rules about honest weights and measures were both religious laws and community standards.

With social friction diminished, we increasingly rely on legal rather than cultural enforcement, replacing informal community standards with formal laws.

Is it really an improvement to go from "what will my neighbors think" to "what will my lawyer think"?

This feels like a post that will be a classic. It puts things I've thought about before but never paid full attention to into very clear words. I'll probably be referring people to this.

I do feel that it could have benefitted from slightly more examples in places where you go a little abstract, perhaps hidden away in footnotes, but overall it is excellent.

Thanks for writing it.